Jody Armour is the Roy P. Crocker Professor of Law at the University of Southern California. He studies issues of race and legal decision-making as well as torts and tort reform movements. He also studies and teaches on the intersections of language, the law and ethics. His latest book directly confronts law enforcement and our legal system’s failures and culpabilities in the mass incarceration of people of color.

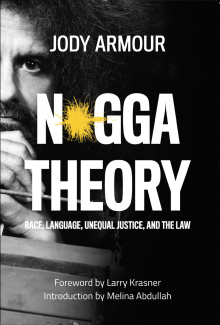

In N*gga Theory, which is how he refers to his work in Critical Race Theory and the title of his new book, Armour systematically identifies and dismantles how our legal system is supposed to work, based on the founding principles upon which our system of jurisprudence is based, and illustrates how those principles are unequally distributed to, and enacted upon, people of color. His arguments, supported by previous legal precedents and the work and results of other researchers, are challenging, compelling, and, in many cases, impossible to ignore.

The text is dense, but the logic of Armour’s reasoning is easy to follow. Sprinkled throughout, he relates his own experiences with the legal system. These include how his own father was unjustly arrested and incarcerated while a child (His father was able to research and rebut the charges against him from within his cell, although it took years to do so.); Armour’s own experiences with law enforcement (and his fears for his sons); and his experiences as a person of color in the academic community, including how he has been told recently by his law students how his “escalating afro” is “ironic” for a law professor because it makes him “look like a criminal.”

Armour also examines social constructions that impact the identities of people of color within the US: language, appearance and the classifications of “good negroes” and “niggas” (and how within the black community there are struggles to be seen as the former, and avoid or subvert the latter).

While Armour does not shy away from the negative results of centuries of societal and judicial inequities, the most surprising thing to readers may be the positive outcome for which he is arguing. He is arguing for a shift in our legal system from one focused on “retribution, retaliation and revenge” to one that would result in “restoration, rehabilitation and redemption.”

Another element that Armour highlights is the supposedly amoral concept of luck, the distribution and impact of resources beyond an individual’s control upon their lives, and the moralizing that is visited upon people as their lives unfold. Simply put: bad luck, generally, happens to “bad” people, good luck being granted to “good.” Armour’s argument, in its entirety, is far more complex.

Luck certainly must be with Armour. For there is no way, after years of research, teaching, writing and living through the experiences related in the book, anyone could have planned for or ensured that his work would be brought to readers at a more critical time. As our culture struggles with the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Elijah McClain, to name only a few, and people continue to protest for change and question their own culpability in systemic racism, the publication of Armour’s book now could not be more fortuitous. Armour has done the work and given us his findings. His work deserves to be read, shared, and discussed. What we choose to do with it is up to us.

Here is an interview with the author.