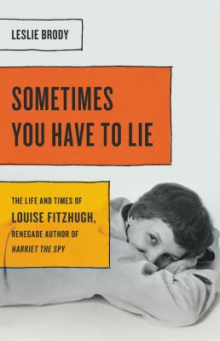

When the children's novel Harriet the Spy was published it received positive and negative criticism, and there was some alarm, even by librarians, about the main character, a cantakorous child, who is a spy. Harriet is an eleven-year-old who keeps a notebook, really a diary, with her observations about classmates, neighbors and family. When another child steals the notebook, classmates read Harriet's notes and start bullying her. In today's world the fictional Harriet would be considered an outlier, a renegade and a victim, who is entitled to free speech--certainly in a novel. The book's debut was in 1964, and the book may still be the object of concern, perhaps even attempted censorship. Harriet, very much like her creator, was way ahead of her time, although not for the children who read the book and loved it. It spoke to children who did not fit in with other children, did not have many friends, and for the most part did not like school. The title of this new biography comes from the mouth of Ole Golly, Harriet's nanny, who advises her charge that, "Sometimes you have to lie. But to yourself you must always tell the truth." Louise Fitzhugh was honest with herself and, for the most part, with others, about who she was, a lesbian, and what she wanted to do with her life, first be a visual artist and later on a writer. Throughout her life, her uvarnished honesty brought satisfaction, along with problems and definitely anxieties.

Fitzhugh's home was in Memphis, Tennessee, where she had a reputation as being reckless, and dressed and did what she wanted: her hair was cut very short and she wore tomboy clothes well into young adulthood. She had major issues with her parents that emanated from their divorce, and how she was left on a couch by her mother when she walked out on her husband. There were other questions and mysteries about her family that plagued Fitzhugh. In 1948, while working at the Memphis Commercial Appeal, Louise found a clippings file that documented the 1927 scandalous breakup of her parents and some other sensational information about them. Some of the missing pieces were filled in, but the young woman's anger and discontent with her family and with life in the South were not resolved.

Louise Fitzhugh's life as a student at Bard College was short and she found her way to 1950s Greenwich Village, where there was a world of people who were creative and open to different ways of life. Along with her interest in writing, she was a talented visual artist and took classes at Cooper Union and the Art Students League. Eventually Fitzhugh made her way to France and Italy for more art instruction and exploration. Biographer Leslie Brody writes about the many writers, artists, editors and educators who were part of this very rich period in New York and in Europe, and many of them were part of Fitzhugh's life, as mentors and friends. Throughout those years, she found loving relationships, that for her, were not always smooth and harmonious.

Harriet the Spy is Fitzhugh's best known book for children, even though she wrote and illustrated other books, which the Los Angeles Public Library owns. In 1964, Harriet and her creator, Louise Fitzhugh, were looked upon as unappealing, but time and changes in attitudes have worn well on their innate spirit and independence. Early on in her fictitious life, Harriet was recognized as a cover for queer identity, which has validity, but her personality and character traits have universal appeal. Above all, Harriet has always spoken to children who do not fit in with other children, in an obvious and not obvious way; she is precocious and with a very strong personality and cannot be easily manipulated by other children, nor by adults; she cannot stand phonies; and she will not put up or shut up with her opinions. Most importantly, she really is not a spy, someone out to gather information to use against others, but an artist gathering information for her writing. This children's novel has had resonance well past its 1964 debut. Harriet's/Fitzhugh's voice reaches into this century, albeit in a "A satirical 2017 article, 'An Open Letter to Robert Mueller from the Association of Super Secret Detectives.' It amusingly recommends that Mueller invite Harriet to join his team investigating Russian interference in the 2016 US elections. If only."(p. 279)