This post is the nineteenth in a series of excerpts serializing the book Feels Like Home.

Chapter 9

The Early Days at New Central - part 2 by by Bob Anderson, Librarian, Literature and Fiction Department

The entire Central Library collection had been barcoded by staff after being shelved in its new home during the summer of 1993. At that point, only a couple of branch collections had been barcoded as pilot projects, and their holdings had begun to show up in the online catalog; as I recall, Mar Vista was the first of these. For Central Library’s collection, each item in the catalog had two “smart” barcodes specific to that item (one reference, one circulating), and all additional copies beyond this were barcoded with “dumb” or generic barcodes. On opening day, and for some time thereafter, Central’s holdings had not been made “live” in the catalog, so only the smart barcodes were listed in the holdings—one reference copy and one circulating copy for every single book—even those in Rare Books! Needless to say, this caused some initial confusion for both staff and patrons.

Eventually when the collection went live, all the dumb barcodes were supposed to appear in the holdings and all the unused smart barcodes (mostly circulating copies of reference only books) were supposed to disappear, but not surprisingly there were some glitches along the way. Certain groups of unused smart barcodes remained behind in the catalog; in Literature, this problem was mainly in the 809.2’s, for some reason. And the system was confused by odd fiction call numbers like “Ed. b”, and many of these barcodes “migrated” to other completely different books that had the same “Ed.” call number, with the result that some records would show 15 or 20 supposed copies of books (half reference, half circulating), and it was impossible to tell which represented actual books. All this took well over a year to straighten out, and some of it was never completely fixed. Twenty-five years later, I still find “phantom” barcodes in the 809.2’s and our messenger clerks still discover closed-stacks books that never got barcoded at all!

The telephone system was another big issue in the early days of “New Central”. In those pre-internet days, we received many, many phone calls asking short-answer trivia questions, or whether a book was on the shelf or in the collection. In most of the larger subject departments, both pre-fire and on Spring Street, we had a phone system with four reference lines, and it was very common to have all four of those on hold while clerks were searching for books, or we were looking for the answer to a reference question. It was quite a shock when we learned that our new telephone system would just have one reference line at each workstation, and that library administration had signed off on this. The phone company people were surprised when we raised this objection; they had assumed (because no one told them differently) that we would deal with one call at a time, finish that one, and go on to the next one. They came up with a solution of sorts; if we had someone on hold waiting for an answer, we could transfer that call to another line so our mainline would open up for another call. This proved to be extremely cumbersome, and most of us settled for answering one call at a time and letting other callers wait.

The initial plan for the reopened building had been to have a large walk-in reference and telephone area on the first floor where the Popular Library is now located. It was supposed to have a dedicated staff, but since there had been staff cuts rather than additions, that did not happen, and the subject departments wound up staffing that desk in the early days. The subject departments’ direct phone numbers were also widely publicized in those days and appeared in telephone books, so a smaller percentage of calls went to the centralized number. It would be several years before staff levels rose to the point that InfoNow was created to handle a large portion of telephone calls.

Another big issue in the first years back at Central Library was Sunday hours. In 1993, no LAPL agency had been open on Sundays for many, many years. As part of Central’s opening celebration, it was announced that the building would be open on Sunday afternoons for the first month, using volunteer staff from throughout the system who wanted to work overtime. Sundays proved extremely popular with the public, and what began as a temporary arrangement was turned into a permanent one.

Since overtime had only been approved for those few weeks, the Sunday situation became increasingly complex and required protracted negotiations between library unions and administration. While the negotiating was going on, Sundays remained voluntary, but those who worked them would get hours off other days of the week rather than overtime. As a result, the number of volunteers gradually diminished. It was not unusual for entire subject departments to be staffed on Sundays with employees from other departments and agencies, which caused problems as well. It took quite a few years before the current Sunday hours procedures were agreed on and Sunday became a regular part of the work week for Central and regional branch staff.

One feature of the restored Central Library that no longer exists is the Translogic system. Translogic was built into the new Bradley wing while it was under construction. It consisted of an electronic rail system with lidded carts to transfer books and other materials from one part of the building to another. It somewhat resembled a miniature roller coaster, with its steep ascents and descents; I understand that it even traveled upside down in some of the segments hidden away from the public eye. There were, I believe, 17 stations, located at each reference desk and each closed stacks area. You would place some books in a cart, snap the lid closed, turn the dial to the number of the station where you wanted to send the books, then press a button. With a couple of beeps, the cart would shoot off, and another empty one would appear in its place. It took a number of months after the grand opening before Translogic was operational; it had to pass a number of fire department inspections. Like the rest of the building, it had its own fire doors. While Translogic was still in the planning stage, there was talk of using it to save patrons from having to go from floor to floor. If they came to a particular department and some items they wanted were on other floors, the staff would call the other departments and have the books sent via Translogic.

By the time we actually opened, it was clear that this much use would overtax the system, and we mainly used it to request periodicals and microfilm, though sometimes we would send books from other floors back to their correct departments. But all those heavy periodical volumes took their own toll on the system, and it was frequently out of order. The amount we could send in one cart was gradually lowered until we were only allowed to send one large or medium-sized volume at a time, despite the carts’ size suggesting that they could hold much more. The cost of the constant repairs and the system’s inefficiency eventually led to its discontinuation, but it was a rather charming addition to Central Library while it lasted, even if it never worked as advertised.

About 100 days after our opening day, the Northridge Earthquake hit Los Angeles. It occurred at 4:30 in the morning and happened to be on the Martin Luther King holiday, so Central Library staff had a little time to get our own lives in order before returning to work. The building did not have any major damage and could reopen fairly quickly, though of course much of the collection wound up on the floor, particularly on the upper levels. The basement floors moved along with the earth and had relatively few books to reshelve. The worst job was dealing with the compact shelving, which had to be opened aisle by aisle; as each pair of shelves separated, dozens of books would fall to the floor. While Central Library’s recovery was quick, many branch buildings, particularly in the San Fernando Valley, sustained such severe damage that they were closed for extended periods. As a result, we experienced a reversal of what had happened during the years after the fire. This time it was Central staff’s turn to host many of our branch colleagues, just as they had made us feel welcome in the aftermath of that earlier disaster.

Robert Anderson became a librarian in what was then the Fiction Department of Los Angeles Public Library in 1980. In 1991 he was selected as Fiction Subject Specialist for the Literature and Fiction Department and has held that position since then. He was, rather ironically, working on a weeding project in the Central Library closed stacks on the day of the 1986 fire, and he considers the subsequent seven years that ended in the Grand Reopening to be the most traumatic but also the most transforming and inspiring of his life and career.

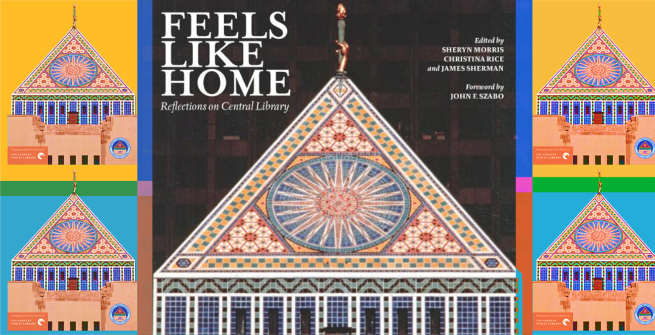

Feels Like Home: Reflections on Central Library: Photographs From the Collection of Los Angeles Public Library (2018) is a tribute to Central Library and follows the history from its origins as a mere idea to its phoenix-like reopening in 1993. Published by Photo Friends of the Los Angeles Public Library, it features both researched historical accounts and first-person remembrances. The book was edited by Christina Rice, Senior Librarian of the LAPL Photo Collection, and Literature Librarians Sheryn Morris and James Sherman.The book can be purchased through the Library Foundation of Los Angeles Bookstore.