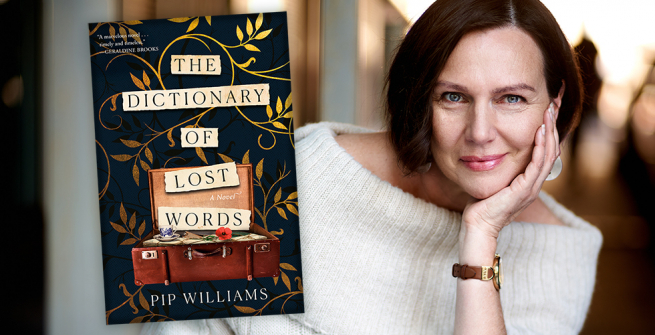

Pip Williams was born in London, grew up in Sydney, and now lives in Australia’s Adelaide Hills. She is the author of One Italian Summer, a memoir of her family's travels in search of the good life, which was published in Australia to wide acclaim. Based on her original research in the Oxford English Dictionary archives, The Dictionary of Lost Words is her first novel and she recently talked about it with Daryl Maxwell for the LAPL Blog.

What was your inspiration for The Dictionary of Lost Words?

I’d read and enjoyed Simon Winchester’s The Professor and the Madman, a book about the relationship between the editor of the Oxford English Dictionary, James Murray, and one of the volunteers who supplied examples of how words had been used in literature. I became fascinated by the process of compiling the Dictionary, but when I’d finished reading, there were niggling questions I could find no answers for. For example, if everyone involved in defining the words were men, then how well did that first edition of the OED represent the way women used words? If all the words in the OED had to have a textual source (which they did), then what words might have been lost because they were never written down—words spoken by the illiterate, the poor, or women doing women’s work. I read a bit more and looked things up online, but I couldn’t find answers to these questions. What I did find, though, was a curious little story about a lost word.

The word "bondmaid" was discovered missing from the first volume of words in 1901. It should have been between "bondly" and "bondman", but it wasn’t. The word means slave girl, and no one knows how it went missing. It is a mystery ripe for solving, I thought, and that is when the seed of an idea for a story began to grow.

Many of the characters in the books are based on individuals that were involved in the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary. Others are of your own creation. Are Esme or any of the other characters you created for the novel inspired by or based on specific individuals?

In many ways, Esme is inspired by the many women who contributed to that first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. They included paid assistants, volunteers who sent in examples of how words were used in text, and women who engaged with the words that were finally published. The only character in the novel who is based on a real person is Ditte, Esme’s godmother. Ditte is a fictionalized version of a woman called Edith Thompson. The dilemma I had was whether or not to name Edith Thompson—she was involved in the OED as a volunteer contributor and proofreader from the letter A to the letter Z and yet so little is written about her in the official history. What I did know about her was interesting and relevant to the story I was telling. As I wrote, she became Esme’s godmother. Of course, this was not a possibility in real life, and everything I’ve written about their relationship is a complete fiction, but I think it rings true to the Edith I came to know during my research. Right up until the book went to the printers, I was debating whether to give her a pseudonym, just to be safe, just to avoid any criticism. In the end, I decided I wanted people to know about Edith Thompson and her role in the development of the Dictionary. I let her keep her real name because I did not want her overlooked, and I couldn’t bear to excise her from my story. But to acknowledge that the relationship between Esme and Edith is fiction, I let Esme give her the nickname, Ditte.

How did the novel evolve and change as you wrote and revised it? Are there any characters or scenes that were lost in the process that you wish had made it to the published version?

I had a big picture idea of where the novel would go and what some of the key moments would be, but as I wrote each scene anything could happen. This was due to two things, the characters and the research. Sometimes as I wrote, a character would say or do something that I hadn’t planned or anticipated, but which seemed perfectly natural. Other times, I would do a bit of research to understand the context my characters were in and discover something that I couldn’t ignore. The suffrage storyline ended up being far stronger than it might have been. I hadn’t realized when I started writing, how close the timelines of the OED and the women’s suffrage movement in the UK were. They are stories that history has kept separate, but for me, they wrapped around each other in a way that I think still resonates today. When I realized that women in the UK were finally given equal political rights to men within weeks of the OED being completed (in 1928) it felt like a gift, but also a validation of the story I was telling.

As for scenes that didn’t make the cut, there weren’t many. As with the Dictionary, there are words that have been sacrificed in the interests of space, and others that I am saving for another story.

How familiar were you with the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary prior to writing The Dictionary of Lost Words? How long did it take you to do the research that you did and then write the novel?

I knew nothing about the creation of the OED before reading the Professor and the Madman. That book made me curious about whether words might mean different things to men and women; it made me wonder if it mattered that the English language was being defined by me, from books written mostly by men. It sent me to the library to find out more (the internet can only take you so far—the library is where all the beautiful detail lies). That detail gave me what I needed to create the world of the Scriptorium and to imagine what it might be like for a little girl to grow up amongst all those words at a time of such social and political change.

So I read enough to understand the context in a general way and then I started writing. The writing informed my research and then the research informed my writing. I would shift between the two activities constantly. In the end, the book took two years to complete and I loved every minute of it.

What was the most interesting or surprising thing that you learned about the OED, and the people that worked on it, during your research?

That the idea for the Dictionary started with a group of Philologists who were part of the intriguingly named Unregistered Words Committee. That these highly educated and privileged men didn’t have the skills to make the Dictionary a success and so turned to a Scottish school teacher to take over as editor. That this school teacher, James Murray, set up his Scriptorium in a garden shed in his back garden and relied heavily on his 11 children to help sort slips of words. That there were a number of women on the payroll of the Dictionary, but none had any decision making capacity. That during WWI proof pages were sent to a lexicographer in the trenches to be edited and sent back to Oxford.

Did you have a “favorite” word prior to beginning your work on The Dictionary of Lost Words? After you finished?

Kindness was my favorite word before I started writing The Dictionary of Lost Words, and kindness is still my favorite word. I hope it never becomes obsolete through lack of relevance.

I’ve also always been fond of discombobulated, and since finishing the book I have a greater appreciation for knackered (worn out), and froudacious (lying), as well as a few words that were obsolete even at the time they were defined, like anywhen (any time), breel (a worthless, good for nothing fellow) and slummock (to kiss amorously, in a particularly wet and slobbery way).

My favorite new word from 2020 is anthropause (a global slowdown of travel and other human activities)—I’m hoping we retain some of the lessons we may have learned during this slowdown.

What’s currently on your nightstand?

Hamnet, by Maggie O’Farrell

Stone Sky Gold Mountain, By Mirandi Riwoe

Little Fires Everywhere, by Celeste Ng

Pandora’s Jar, by Natalie Heynes

No Friend but the Mountains, by Behrouz Boochani

A Users Guide to Melancholy, by Mary Ann Lund

A Room of One’s Own, by Virginia Woolf

Can you name your top five favorite or most influential authors?

This list could change tomorrow, but today I would say:

Virginia Woolf (for her non-fiction in particular)

Geraldine Brooks

Margaret Atwood

Douglas Adams

Dr Seuss

What was your favorite book when you were a child?

The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe, by CS Lewis.

Was there a book you felt you needed to hide from your parents?

No, my parents let me read anything. I’m still not sure if was due to an enlightened attitude or benign neglect.

What is a book you've faked reading?

I faked reading Emma, by Jane Austen. It was on the curriculum in high school and I found it incredibly dull. I’ve since read and enjoyed so many of Austen’s books, but have never returned to Emma. These days I don’t need to fake it, I just listen to books I am intimidated by but ‘should’ read—Middlemarch, by George Eliot, springs to mind.

Can you name a book you've bought for the cover?

The Night Circus, by Erin Morgenstern.

Is there a book that changed your life?

No, but there are books I return to because they seem to say something about the complexity of the human experience. Two that come to mind are The Hours, by Michael Cunningham, and The Other Side of You, by Salley Vickers. More recently, there have been books that challenge histories and stereotypes that I have grown up with, such as The Yield, by Tara June Winch, and An American Marriage, by Tayari Jones.

Can you name a book for which you are an evangelist (and you think everyone should read)?

Oh, the Places You’ll Go, by Dr Seuss.

Is there a book you would most want to read again for the first time?

The Shadow of the Wind, by Carlos Ruis Zafon.

What is the last piece of art (music, movies, TV, more traditional art forms) that you've experienced or that has impacted you?

The TV series, Schitt’s Creek. I know I’m a bit late to this, but it took a pandemic for me to find the time to sit for an extended period in front of the TV. I loved the way it normalized diversity. And I loved the way it made me laugh and cry.

What is your idea of THE perfect day (where you could go anywhere/meet with anyone)?

Waking in the old town of just about any town in Italy, grabbing an espresso from the nearest bar, then slowly walking the narrow streets until I come across some subtle reminder that life has been lived in that place for millennia. I would let my fingertips trace the contours of colored tile, or faded fresco or sculptured stone, and imagine a woman, about my age, doing the same a hundred years before, three hundred years before, a thousand years before. I would wonder how our lives are different and how they are the same. Then I would find another bar and pay the premium for an outside table and spend most of the day writing, drinking coffee, and eating. I would observe the life around me, the locals and the tourists, the words and the beggars. I would jot down thoughts, start a letter to a friend, write a page or two in my journal. I might work on my next novel, or I might not—on my perfect day I would feel no compulsion and no guilt. I would meet my partner for dinner and we would eat something with Truffles.

What is the question that you’re always hoping you’ll be asked, but never have been? What is your answer?

I’m always hoping to be asked about my daily writing practice because I think it is brilliant. After trying all sorts of approaches to writing and failing miserably and therefore being miserable (a daily word goal of 1000 words; sitting at the desk for two hours morning and afternoon; writing a page of gibberish before writing ‘the novel’), I decided that my only obligation was to type one word per day. Just one. The beauty of this goal is two-fold. First, the requirement is so insignificant that it is not worthy of the procrastination monkey. Secondly, it is hard to fall short. All I have to do is open my laptop and type one word. It will take a minute, maybe two, and then I am permitted to close my laptop and watch Netflix. But it’s like telling someone who is avoiding exercise that all they are required to do is put on their runners and take one step out the door. Once your runners are on and the door is open, walking is easy. Similarly, once the laptop is open and you’ve typed that first word, the next two or three just tumble out and before you know it you’ve written 100 words, maybe 200 words, sometimes 300 words—at that point you are as good as Virginia Woolf and any more words would be an overachievement.

What are you working on now?

My next novel will be a companion to the Dictionary of Lost Words. Not a prequel or sequel, but a story that takes place in the same universe. It will be about a young woman who works in the Bindery of the Oxford University Press. Her name is Peggy, and she dreams of one day going to Oxford University, but it is an impossible dream. She is told that her job will always be to bind the books, not read them, and never to write them. Then WWI breaks out and the normal order of things changes.