Long before Divine, Charles Pierce, Craig Russell, Jim Bailey, or any contestant on ‘Drag Race’ brought the art of drag performance to mainstream audiences, there was Julian Eltinge. Although remembered (mostly) by historians of queer history, he has been largely forgotten by the mainstream public. In the first half of the twentieth century, Eltinge’s notoriety as a “female impersonator” rivaled that of superstar performer RuPaul’s status today. In fact, Eltinge’s shows and public appearances were heralded throughout the press not only for their entertainment value but for his mastery of the art of impersonation. Julian Eltinge reached a level of fame that seems unfathomable today considering the social constrictions of the age in which he lived but he was, in fact, among the most beloved entertainers of his day. So, exactly who was this king of drag queens?

Eltinge was born in Newton, Massachusetts on May 14, 1881 (some sources say 1883 but it may have been Eltinge shaving off a few years) under the name William Dalton. William’s father, Joseph brought his family to Los Angeles around the time William was five but relocated to Montana at some point where Joseph owned a barbershop. William’s mother, Julia doted on her son and encouraged him to perform and praised his skills when he began dressing up as a female and performing at an early age. By the time he was in his teens, he had landed work performing a drag act in saloons. According to authors Michael Locke and Vincent Brook, when his father learned of his son’s chosen profession, he beat young William so severely that his mother sent him to Boston to ensure his safety. It was in Boston that 18-year-old William came into his own as a performer.

His theatrical career started by changing his name to Julian Eltinge and taking up with a Boston theater group that practiced Shakespeare in its traditional form, i.e. men performing women’s roles. In 1904, Julian ended up in New York where he landed a role in the Broadway musical, Mr. Wix of Wickham a musical featuring music by Jerome Kern. He played a role that he would repeat, in variations, throughout his lifetime; that of a man disguising himself as a woman. His role in Mr. Wix would garner him critical acclaim eventually allowing him to become a headliner within the vaudeville circuit and tour the United States and Europe. A 1904 review from the Boston Globe raved about Eltinge’s style and abilities, drawing comparisons to Harry Lehr, a gilded age society man celebrated for taking female parts in amateur theatrical productions:

"Mr. Eltinge has become the 'Harry Lehr' of Boston, but this is admitted by everybody who has seen the famous New York Society man as unfair to Mr. Eltinge, for the latter displays a genius in the impersonation of female characters which the former could never duplicate. Harry Lehr never saw the day when he could dance with Julian D. Eltinge for one thing, and furthermore, he never could do more than give an amiable burlesque of a young woman. Eltinge can give a counterfeit presentment of a well-bred young woman which almost defies analysis. He has the face and he can make up a figure in a really artistic manner...Eltinge also has the grace and self-poise which a well-bred young woman naturally possesses and he never makes any of those ridiculous mistakes which give the man in woman’s clothes almost invariably 'away'. His is an art which would be difficult to approach."

It goes without saying that Eltinge was going places. At one point he was called on by King Edward VII of England to give a command performance at Windsor Castle. The King presented him with an English Bulldog as a gift of appreciation.

Much of the fascination with Eltinge was based on his uncanny ability to create the illusion that the audience was watching a woman, rather than simply a man in drag. While there is an ongoing debate about what constitutes ‘drag’ vs. ‘female impersonation’ both are done for entertainment purposes and Eltinge was a master at entertaining. In his performances, he utilized both the camp of drag and the more structured art of impersonation to entertain audiences. Eltinge was particularly adept at mimicking the gaudy femininity created by late 19th century female performers like Lillian Russell (lots of makeup, wigs, jewelry, feathers, sequin gowns, oversized hats, corsets, etc.) and he also had the ability to sing in a contralto voice that was, by all accounts, quite lovely and, as a performer, set him in a class all by himself. Eltinge would spellbind audiences by building the illusion of a gilded age era/belle of the nineties woman, complete with song and dance, only to destroy it in an instant with what became his signature move, campily pulling his wig off at the end of the performance to reveal his male identity. Audiences loved it and Eltinge became among the highest paid performers in the United States earning up to $5,000 a week.

Eltinge would enjoy stage success with the musical comedy, The Fascinating Widow which opened on Broadway in 1911. The plot involved the silly story of a young man pretending to be the titular widow so he can get the girl of his dreams. The New York Times dismissed the play but acquiesced in acknowledging that the play was immensely popular with theatergoers: “the impersonator’s popularity is enormous, the theater was crowded and there is every likelihood that it will continue to be filled for many weeks to come.” The musical only had 65 performances on Broadway but toured around the United States for years. The Los Angeles Times was infinitely more kind to the show when it came to the Mason Opera House in October 1912, lavishing Eltinge with praise:

“Music with melody to it, comedy that is actually funny and regular girls, dainty and alive make The Fascinating Widow more than enchanting without the matchless Julian Eltinge and his inimitable impersonation…The Fascinating Widow is better than the New Year’s jinx at the Jonathan Club and not amazingly unlike it except that the women at the latter festivity are all men whom rich gowns and extravagant hair fail to make enchanting...Most persons balk at the idea of the female impersonator. The Eltinge performance is different from all others in that it cannot possibly arouse distaste. The audience is taken into the complete confidence of the young actor and only the people behind the footlights are in the dark...Los Angeles will heartily sustain and laugh itself into hysteria…”

A second stage success came in the form of The Crinoline Girl in 1914, a musical comedy in which the premise required Eltinge to don drag in order to nab diamond thieves and win his prospective father in law’s approval. The play ran for 96 performances on Broadway and toured the country adding to Eltinge’s national notoriety. He would return to the stage, particularly vaudeville establishing his own vaudeville troupe, The Julian Eltinge Players.

Eltinge was also interested in film work and made a handful of films between 1914 and 1925 including film versions of his stage successes, The Fascinating Widow and The Crinoline Girl. Paramount Pictures eagerly trumpeted his arrival anticipating that Julian’s stage success would translate to motion pictures. A trade ad from Paramount Pictures featured in Motion Picture World appeared as follows:

“Unique in the American Theatre, Julian Eltinge has won great fame and thousands of followers because he does one thing better than anyone else. As an impersonator of feminine characterizations, he has no equal. He will appear in a distinctive Paramount photoplay The Countess Charming written by Gelett Burgess and Carolyn Wells providing Mr. Eltinge with the greatest opportunity he has ever had for the display of his amazing abilities in feminine characterizations.”

The trade papers continued trumpeting his name alongside his fellow newcomers like Billie Burke (“Glenda, the Good Witch” in the Wizard of Oz (1939)) and more established stars like Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin, and Douglas Fairbanks. Eltinge made additional films like The Widow’s Might (1918) and Madame Behave (1925), capitalizing on his notoriety by keeping him in drag but also turning him into a one-trick-pony by failing to allow him to show any range as a performer.

The immense wealth Eltinge accrued from his stage and film work in addition to his endorsement line of various goods (corsets, cigars, makeup, facial creams, and lifestyle/beauty magazines) allowed him to relocate to Los Angeles where he built one of the most stylish mansions early L.A. had seen. Eltinge commissioned the architectural firm of Pierpont and Davis to build a lavish style home in the Edendale region surrounding the Silverlake reservoir. The building was christened Villa Capistrano and appeared on postcards and in a number of architectural magazines including a feature in The Architectural Record. The building remains standing and has since been identified by the Los Angeles Conservancy as a building with historic significance.

Eltinge’s personal life remains shrouded in mystery although most accounts credibly assume that he was gay. Eltinge lived and worked in a time when homosexuality was criminalized necessitating a life in the closet. In a 1937 interview with Eltinge, the Los Angeles Times, writer Louis Banks stated: “...and there lies the greatest challenge that Julian Eltinge had to meet: the popular idea that there must be ‘something wrong’ with a man who wanted to put on women’s clothes.” Descriptions of Eltinge often used wording, describing his personality as “gay” and assigning him labels like “lifetime bachelor.” As a countermeasure, press stories about Eltinge’s hyper-masculine activities off stage were awash in the press: It was reported that Eltinge smoked, drank, cursed, rode horses, broke engagements to dozens of women and regularly got in fistfights with men who questioned his masculinity. When magazine The Architectural Record toured his Edendale home, the writer felt it necessary to inject superfluous gendered language into the description to assert Eltinge’s masculinity: “It has been suggested that the interior of the Eltinge house should be described by a woman, it so distinctly a man’s house...some women might not like them [the stairs leading to the living area] but this is not a woman’s house!” Of course, this last statement only stood to emphasize the fact that, with the exception of his mother, women were noticeably absent from his public and private life. Eltinge never married and was never credibly linked to a relationship with either a woman or a man and he never discussed details of his personal life. Eltinge was quick to dismiss reports that he was the ill-tempered he-man who got into fisticuffs with strangers: “Every so often press stories would say that I knocked down this man and that man for insulting me but they were wholly exaggerated.” When his sexuality was called into question, he responded with a snappy line telling reporters saying, “I’m not gay, I just like pearls!” An interesting coincidence is that Silverlake, and the Edendale area in particular, where Eltinge lived ultimately became an epicenter of LGBT activism in Los Angeles; although Eltinge passed away long before either the founding of the Mattachine Society or the Black Cat Tavern riots occurred, his residency is looked at as one of the milestones of Silverlake’s LGBT history.

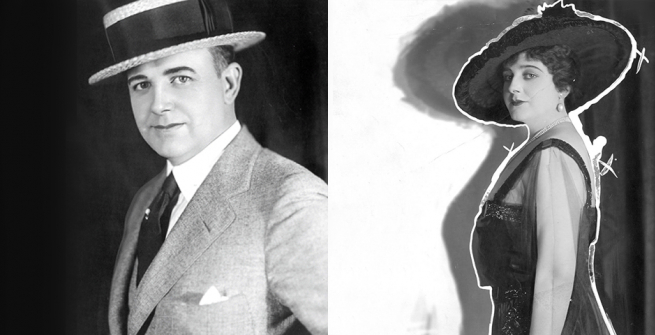

Eltinge, [ca. 1920]. Herald Examiner Collection

Drag performance would enjoy a renaissance in the prohibition years during what LGBT scholars refer to as the “pansy craze”. As nightlife went underground, drag performers became a welcome staple at nightclubs in the metropolitan areas. Eltinge attempted to inject himself into this setting but the fact was that, although he remained an excellent performer, he rather ironically, was now subject to the same scrutiny that the women he was attempting to emulate would probably be subjected to. In 1927 the Los Angeles Times reviewed his new show and gave the following critique:

“Eltinge is a trifle too old and portly to exactly suggest the flapper - his impersonation is limited to the more matronly of the species. When one says that he can pass as a woman one says all; interest in him is purely academic.”

The fact was that Eltinge’s “fascinating widow” was simply too dated in an era rife with drag queens emulating flappers and jazz babies. Eltinge conceded that he was becoming a relic: “I do not want to imitate women because I would have to be a woman of the forties - and no one is particularly interested in seeing an imitation of a woman [in their] forties.” Eltinge made his last drag film appearance in the pre-code comedy Maid to Order (1931), a poverty row cheapie that didn’t do much to advance his career. The end of prohibition in 1933 put the kibosh on the “pansy craze” and enforcement of the Hays Code in 1934 meant that films that might hint at a “deviant” sexuality would no longer be tolerated. Eltinge struggled to maintain a career in the interim and in 1937 he gave an interview with the Los Angeles Times in which he voiced his frustrations with the inability of producers to see past his years in a dress. The article, “The Man Who’s Tired of Wearing Skirts”, showed a man in his fifties who yearned to be cast in character parts to reinvigorate his career. He acknowledged that, for better or worse, his name was so closely associated with female impersonation that he was unable to escape typecasting. His final film appearance came in a small role in the Bing Crosby film If I Had My Way (1940); he did not appear in drag.

Despite the run of bad luck his career hit, he had invested his money wisely. In 1939, a very bad investment forced him to sell his Edendale property in order to have access to his money, but the financial loss didn’t spell disaster. He maintained properties in Studio City where he spent his remaining years and owned part of a San Diego ranch that he was gradually selling off in order to re-acquire the Edendale property but it never happened. While in New York during March 1941, he was hospitalized for what was reported as a kidney ailment. His death notice reported that he died from a “related complication” but his cause of death was listed as a cerebral hemorrhage. His funeral took place in New York and included over 300 mourners. He was cremated and his ashes sent to Los Angeles to be interred at Forest Lawn in Glendale. His will left everything to his only survivor, his 79-year-old mother.

Further Reading