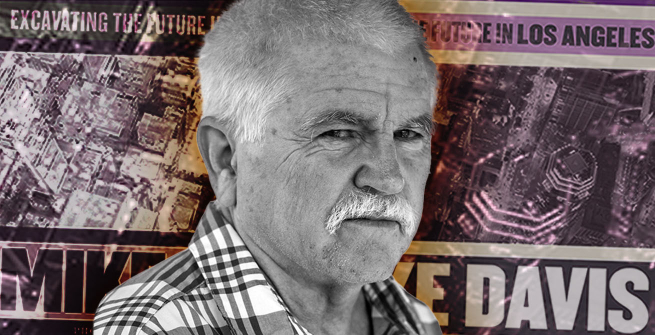

On Tuesday, October 25, Mike Davis, the towering left-wing polemicist, passed away at his home in San Diego at the age of 76. Accessible and hard-hitting in the greatest journalism tradition, Davis leaves a most rigorous, expansive, and idiocratic political bibliography. Between 1986 and 2020, Davis published 15 books of non-fiction, edited several anthologies, and wrote countless articles for outlets big and small. Most closely associated with a synthesis of urbanism, political theory, and historical materialism with an acid tongue, Davis carved out a unique position as a public intellectual and renegade scholar with a particular interest in Los Angeles and Southern California.

Born in Fontana, California, in 1946 to a working-class family, a young Davis followed his father into the unionized butchery trade and shortly became politicalized after attending a civil rights protest. This spark grew into a chaotic and formative decade that led him through stints at Reed College as a student, a leadership position with Students for a Democratic Society, managing the Southern California Communist Party’s bookstore (which stood not far from the Westwood Branch Library) working as a Teamster trucker, another go at college (this time UCLA), a pivotal tenure with the British journal New Left Review, and finally a return to his home in Southern California.

Equidistant from Fontana are both Los Angeles and Llano del Rio, each weighing into City of Quartz: Excavating the Future in Los Angeles (1990), Davis' second book and first to find him a popular audience. L.A. is the nominal city, described as a site of surveilled and alienated citizens fighting for resources in a zero-sum game of survival, in a city invested not in its people and public institutions but in a bid for endless privatized growth. Tracing histories as disparate as home-owners associations, political leadership in the Catholic church, the War on Drugs, and "hardened" public spaces, Davis' Los Angeles is an endlessly fascinating and sprawling network.

The book’s subtitle gives a clue to one of Davis’ goals; to envision and enact a more safe, just, and equitable future for Los Angeles, the reader must accurately see the present and understand the past. So, it is the failed early-20th-century utopian project of Llano del Rio that the book begins. Llano del Rio represents a lost future, what he calls the "utopian antipode" of "Open Shop Los Angeles," where participants could “taste the sweet fruit of cooperative labor in their own lifetimes.” It is no wonder that Science-Fiction author William Gibson, offers a top blurb on City of Quartz’s back cover; "more cyberpunk than any work of fiction could ever be.” Davis asks if Llano del Rio is a place that we once had, and the City of Quartz is what we have now, then what kind of a future do we want?

This question resonated outside of the academy and activist circles, and the book became a surprise success. No doubt bolstered by a fondness for folding popular cultural criticism in the mix (film noir, East L.A. muralling, and N.W.A. all got a look), Davis was also an undeniable stylist. Bombastic, fatalistic, and writing with stunning moral clarity and dark humor, as if Jean Baudrillard was a homegrown Southern Californian who ditched the academy to be a beat reporter for the local weekly. Frequently, Davis’ perspective was too severe to entertain ideas of reform, but his diagnoses, even if the reader didn’t agree with them, were always spiritedly argued.

Virtually no institution was immune from Davis’ critique, and in an exemplary passage, Los Angeles Public Library’s own Frances Howard Goldwyn Regional Branch gets a singular reading:

This is undoubtedly the most menacing library ever built, a bizarre hybrid (on the outside) of dry-docked dreadnought and Gunga Din fort. With its fifteen-foot security walls of stucco-covered concrete block, its anti-graffiti barricades covered in ceramic tile, its sunken entrance protected by ten-foot steel stacks, and its stylized sentry boxes perched precariously on each side, the Goldwyn Library (influenced by Gehry's 1980 high-security design for the US Chancellery in Damascus) projects the same kind of macho exaggeration as Dirty Harry's 44 Magnum.

One assumes he reached the library during closed hours, as he doesn’t mention the inviting interior, comfortable seating, and outstanding staff!

Two years following publication, City of Quartz’s exposure was magnified when the L.A. Riots occurred. "Spatial apartheid" was the term Davis used to describe the racial and class inequity and geographic isolation that was systemically maintained by a monied power structure; many found the book prescient. For a period, Davis spoke to the press prolifically and even began a book about the riots themselves. Shortly though, he disappeared from public appearances and passed on the book opportunity, citing that the book shouldn’t be written by an outsider like himself. During this time, he continued involvement in the labor movement and fought for the Peace Process Task Force, a Senate Bill assisting in gang truces. Notoriously generous with his time and energy, he was also a dedicated correspondent and a supportive mentor to fellow writers, counting among his associates Lynell George, Rubén Martínez, and Gustavo Arellano, among others.

1998 brought Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster, a sequel of sorts to City of Quartz. Like a good sequel, the drama was ratcheted up, and the scale increased to an almost cosmic scale. Rather than the on-the-ground reporting of L.A.’s political machine, Ecology of Fear was concerned with natural disasters, their human consequences, and government response. Earthquakes, hurricanes, and forest fires; as stormy as Davis’ outlook was, the book draws from his genuine curiosity of geography and earth sciences, and his analysis remains accurate enough that the star chapter from the collection, "The Case for Letting Malibu Burn," reliably circulates on social media every fire season in California.

Davis entered a more prolific period in the subsequent years. While Los Angeles and neighboring cities remained a concern Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the U.S. Big City (2000), and Under the Perfect Sun: The San Diego Tourists Never See (2005), there was an increased interest in how politics play out on a global scale. Late Victorian Holocausts: El Niño Famines and the Making of the Third World continues his work on extreme weather, exploring its human implications in colonial India. The Monster at Our Door: The Global Threat of Avian Flu (2005), written in anxious anticipation of H5N1, is an impassioned assessment of both the causes (pharmaceutical and factory farming, among others), as well as the lack of infrastructure for responding to such an event. Davis’ prescience eerily continues, with the volume having been rediscovered in the wake of COVID-19. Planet of Slums (2006) attempted to understand the shifts happening with cities through a Marxist perspective on labor and informal job markets as populations shift from rural to urban dwellings in increasing numbers.

Returning both to Los Angeles and to his decade of formative political education, Set the Night on Fire: L.A. in the Sixties, co-written with historian Jon Wiener, set out to be a corrective to the “great man” theory of history, instead centering on the waning and waxing power intersectional movements held within the city during a time of globalization and deindustrialization. While Set the Night on Fire shows Davis as unsentimental as ever (he frequently demurred that the activists of the Civil Rights era were far more successful than the New Left of the 1960s), the book serves not only as an instructive organizing text but also as a celebration of a spirit and values he championed throughout his life, in his own fiery way.