While scouring microfilm in the History & Genealogy Department at Central Library a few months back, I was startled to see a name that seemed entirely out of place in a particular publication. The name seemed out of place because it was in the theatrical section of a 2012 New York newspaper and, despite some opinions to the contrary, the individual mentioned was neither an actress, a director, or producer. In fact, she had no connections to modern New York’s theater scene at all because she had died nearly 70 years earlier. The article was related to the closure of a Broadway show called Scandalous and, while the columnist’s intent was largely to take a swipe at the show’s writer, a well-known television personality, the critic also managed to make the statement that the show was about a woman that “nobody knows.” My initial reaction upon reading this was surprising because the idea that “nobody knows” Aimee Semple McPherson was just ludicrous.

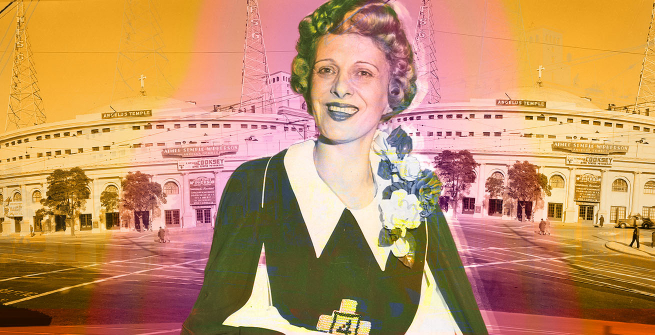

The founder of the International Church of the Foursquare Gospel (and the person responsible for the landmark Angelus Temple in Echo Park), “Sister” Aimee was one of the most beloved and controversial figures in our city’s history. Originally from Canada, Aimee arrived in Los Angeles in 1918 after finding her calling as a Pentecostal preacher. Aimee’s niche was faith healing and sermons that were brought to life through lavish stage productions—a style that was well-suited to a town that would become synonymous with the entertainment industry. By acquiring a broadcasting license she was able to spread her gospel far and wide and she built a devoted following. Outside of the movie colony, Aimee was, perhaps, the most famous and powerful woman in 1920s Los Angeles, but her style of evangelism ruffled the feathers of more orthodox religious leaders. Aimee gained her share of critics and slogged through blatant misogyny from civic leaders who were unaccustomed to women attaining prominence (and power) through religion. She was subject to intense scrutiny during her first decade in L.A. but her resilience in the face of this criticism was remarkable. Aimee remained a prominent Angeleno throughout her lifetime and helped our city with some exceptional charitable work during some very dark times. Not only did she and her church feed countless Angelenos during the Great Depression, but her sermons also helped to keep many spirits buoyed as L.A. struggled to get back on its feet. Much of the popular preoccupation with Aimee, however, hinges on a single incident: her 1926 disappearance.

When Aimee disappeared while swimming off Venice Beach in May 1926, it was initially believed that she had drowned. A month later, however, she miraculously reemerged with a wild story about being kidnapped, taken to Mexico, and tortured before escaping. Her critics challenged that story, claiming it was a hoax and countered that she had actually run away to Carmel-by-the-sea with a married employee, Kenneth Ormiston, using the kidnapping story as a front for romantic indiscretions. For better and worse, this incident coupled with a trial (where charges of criminal conspiracy, perjury, and obstruction of justice were ultimately dropped) propelled Aimee into the role of a nationally recognized celebrity. Her name was splashed across newspapers and magazines from D.C. to San Francisco for months prompting endless speculation about her moral character and morbid fixation on “what really happened.” While Aimee quickly put this incident behind her, the public never really did and endless speculation persists to this day. This lone incident and the fact that it was never really resolved constructed mythology around her that has kept the public intrigued for more than a century. Consequently, Aimee has a permanent “is she a sinner or a saint?” footnote tacked onto her legacy, and nowhere is this more apparent than in popular culture where novelists, filmmakers, songwriters, and poets (just to name a few) are all free to speculate, ruminate, and reimagine events in the life of “Sister” Aimee Semple McPherson.

Appearing as herself or veiled as a “character-based upon,” Aimee has been the subject of countless narratives both fictive and factual for nearly a century. Her spirit is invoked to add dimension, create moral ambiguity, explore faith, humanity, or hypocrisy within the lore of Los Angeles. She has been depicted as both sinner and saint, venal and altruistic, charlatan and miracle worker. In the popular imagination, she may be all these things or she may be none of them but she is far from forgotten. Let’s walk back that grossly uninformed statement that Aimee is an evangelist that “nobody knows” by looking at the works she has inspired throughout the past century. In no way is this intended to be a comprehensive list, just a reminder that for nearly 100 years, this Los Angeles woman has never been forgotten.

Elmer Gantry (1927)

The same year Aimee disappeared, Sinclair Lewis began writing a scathing novel about religious hypocrisy. The book, Elmer Gantry, was published the following year and people couldn’t help but draw comparisons between evangelist Sharon Falconer and Sister Aimee. A few months after Aimee’s trial ended, The Leader-Post, a Saskatchewan newspaper wrote about Elmer Gantry and pointed to recent events, “One Aimee Semple McPherson, an evangelist of sorts, was much in the mind when this book was first distributed. It seemed to most readers that the book pointed at her type, if not directly at her. This same Aimee Semple McPherson is again on page one of the newspapers and the new incidents remind us strikingly of the book Elmer Gantry.” Falconer, a holy woman in the mold of Aimee, fills tents with parishioners eager to hear her preach and give their money to witness her perform miracles. Much like McPherson, Falconer’s faith healing became a vital part of her sermons and Lewis’ cynicism is less focused on the evangelist than the people who followed her: “It was not her eloquence but her healing of the sick which raised Sharon to such eminence that she promised to become the most renowned evangelist in America. People were tired of eloquence and the whole evangelist business was limited since even the most ardent were not likely to be saved more than three or four times. But they could be healed constantly, and of the same disease.”

Falconer seems to alternate between a fervent belief in her own divinity and undermining it completely. In one conversation with the title character, Elmer concludes that Falconer is “crazy” as he watches her become possessed with a spiritual zeal that consumes her: “I can’t sin! I am above sin! I am really and truly sanctified!...I can do anything I want to! God chose me to do his work. I am the reincarnation of Joan of Arc, of Catherine of Sienna! I have visions! God talks to me!” The following day she has come back down to earth and tells Gantry “What I need tonight is some salve for my vanity. Have I even told you I was a reincarnated Joan of Arc? I really do half believe that sometimes. Of course, it’s just insanity. Actually, I'm a very ignorant young woman with a lot of misdirected energy and some tiny idealism. I preach elegant sermons for six weeks but if I stayed in a town six weeks and one day, I’d have to start the music box over again. I can talk my sermons beautifully...but Cecil wrote most of them for me, and the rest I cheerfully stole.” Sharon’s story ends with her belief that she can walk, untouched, through a fire that has consumed her tent. Her charred body is found the following day with a cross still clutched in her hand.

Oil! (1927)

“The story spread all over the front page day after day. The body of Eli could not be found. The people of the temple employed divers—they had searchlights sweeping the water at night, and thousands of the faithful patrolling the sands, holding revival services there, weeping and praying to God to give them back their beloved leader in his green bathing-suit.”

Like Aimee, Eli miraculously returns to a joyful congregation with a story about being kidnapped that causes many naysayers to raise an eyebrow: “Of course there were skeptics, people with the devil in their hearts who refused to believe Eli’s story and persisted in talking about a blue-colored automobile driven by a good-looking girl, having a heavily veiled man wearing goggles in the seat beside her. They talked about signatures on hotel-registers, hand-writing experts, and other such obscenities; but all that made no difference to the glory-shouters at the Tabernacle, which was packed all day and all night, as never before in the history of religions.”

By switching the gender of the character, Sinclair avoids scrutiny for sexism but Oil! is very much reflective of the author’s deep disdain for organized religion which he called the “source of income to parasites and the natural ally of every form of oppression and exploitation.” It is worth mentioning that this is, very likely, the first in a long line of works that are focused on Aimee’s infamous disappearance but it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Bless You, Sister (1927)

The year after Aimee’s disappearance, a play called Bless You, Sister premiered on Broadway. The play, written by John Meehan and Robert Riskin, starred actress Alice Brady as a preacher’s daughter named Mary McDonald who has lost her faith and is convinced by a slimy conman to become a phony faith healer. Mary’s love for a man complicates her particular grift and threatens to undermine her deception. Brady was unanimously praised for her performance but reviews for the play were mixed. Critics, of course, saw the parallels between Mary McDonald and Aimee Semple McPherson and were eager to report. The New York Daily News wrote that “Alice Brady is playing the first of the dramas inspired by the “religious racket” of which Aimee Semple McPherson and William Sunday are the conspicuous representatives.” Writing for the Chicago Tribune, critic Burns Mantle stated that “the assumption is natural that the recent adventures of Aimee McPherson inspired the writing of the play, but here again, the authors cannot be fairly assessed of lifting more than the idea.” In a profile of the play’s authors, the New York Times stated that “Riskin told Meehan about the play that he had in mind—a play which seemed to naturally to follow in the wake of Elmer Gantry and the Aimee Semple McPherson business, a play based on fake religions and lady evangelists...” The similarities between the play and recent events were not likely to be lost on theater audiences.

Vile Bodies (1930)

Evelyn Waugh’s satirical novel, Vile Bodies, takes place in England during the interwar years and skewers the generation of idle rich young men and women commonly referred to as the “Bright Young Things.” Among the minor characters is a garish American evangelist named Mrs. Melrose Ape who was based on, you guessed it— Aimee. Mrs. Ape is touring Europe with a gaggle of singing, religious-minded young women in tow to help spread the gospel. These women, known as the “Angels,” are dressed in white robes and have ersatz wings on their backs. These “girls” have all been improbably named to correspond with virtues: Faith, Fortitude, Humility, Prudence, Temperance, Chastity, etc. While in England, Mrs. Ape is the guest of honor at a party thrown by the preposterously named aristocrat, Lady Margot Metroland. Simon Barclain, a gossip columnist who crashed the party, twists details of the soiree into salacious fiction after he is forced to leave. Barclain’s libelous reporting involves aristocratic dowagers turning into proverbial “holy rollers” thanks to the sermon Mrs. Ape delivers to partygoers. Barclain escapes the “orgy of litigation” by putting his head in the oven and turning on the gas. Angry partygoers mentioned in the column sue Barclain’s newspaper but “the proceedings were considerably complicated by the behavior of Mrs. Ape, who gave an interview in which she confirmed Simon Barclain’s story. She also caused her press agent to wire a further account to all parts of the world. She then left the country with her Angels, having received a sudden call to ginger up the religious life of Oberammergau.”

Waugh’s novel is incredibly dated and the humor is unmistakably English but it conveys what many people thought of Aimee—that she was a ridiculous self-promoter. By the time Vile Bodies was published, Aimee had visited Europe at least twice: once in April 1926 shortly before her disappearance, and once in 1928, two years after her disappearance. By 1928, Aimee’s infamy had spread around the world and there is little doubt that Waugh wasn’t aware that the flashy “disappearing” American evangelist had landed in Europe while he was working on the book. It should also be noted that Waugh was raised Anglican and he wrote Vile Bodies right before converting to Catholicism so it wouldn’t be far-fetched to assume that his cynicism of Protestant religions was in full gear.

The Miracle Woman (1931)

A play that enjoyed even a small measure of success is likely to catch Hollywood’s attention and Bless You, Sister was no exception. In 1931, legendary director Frank Capra set out to make a film version of the play. In the lead, Capra cast Barbara Stanwyck as the preacher’s daughter. Without access to a copy of the play (it appears to not have been published), it’s hard to find out exactly how the film deviates from the play but a few things are readily apparent including a name change. The title, obviously, was changed to The Miracle Woman, and the name of the evangelist was changed from Mary McDonald to Florence Fallon. No doubt this name change was the result of someone in the movie colony noting the similarities between the surnames of “McDonald'' and “McPherson.” A commanding actress, Stanwyck is the whole show here. She was an ideal choice to play a version of Aimee and she possessed the necessary charisma and fire that made a hokey story entertaining, if not entirely plausible. What is notable here is that Florence is sympathetic. Her willingness to con her followers is directly related to the abuse and hypocrisy that her family has subjected to rather than avarice. The film telegraphs the fact that Florence is inherently a good person because her love for a blind parishioner allows her to recognize how this chicanery has poisoned her humanity. The film was made in the period referred to as the “Pre-code” era when the Hayes production code was unenforced. After 1934, films that critiqued religious clergy or hinted at the corruption of religious leaders would be impossible to produce until the demise of the code in the 1960s. Like Bless You, Sister, the public was aware of who the character was based on even if the filmmakers were ignoring the elephant in the room. Gossip maven Louella Parsons wrote in her February 27, 1931 column that “Columbia denied that it is the story of Aimee Semple McPherson but certainly any female evangelist story made in California must bear the earmarks of Sister McPherson.”

Anything Goes (1934)

It has been generally acknowledged that the character of Reno Sweeney in Cole Porter’s landmark musical, Anything Goes was loosely based on McPherson. Falling into the ‘religion-can-be-entertaining-as-well' mold, Reno Sweeney is both a nightclub singer and evangelist dancing and belting her way through songs that have become American standards. The title song, Anything Goes, laments the state of “modern” morality while Blow, Gabriel, Blow heralds Reno’s salvation. Actress Kara Lane who played Reno in the most recent revival in London was interviewed for the theatrical website, Londontheater1 and shared the research she had gathered on Aimee in order to prepare for the role of Reno Sweeney:

“Reno is based on two real-life women from the 1920s and 1930s; evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson and famous “speak-easy hostess” Texas Guiene [Guinan]. Both women embraced and used to their advantage all the breakthroughs in multimedia and women’s liberation to become the successes they were. They’re both great examples of the modern 1920/30s woman…It’s quite a contradiction that the other side of Reno is so religious and that her nightclub act is a mixture of entertainment and preaching to people to confess their sins. This is the part of Reno that is based on Aimee Semple McPherson. Aimee made a name for herself because of her faith healings. She toured the country with her children and mother preaching the word of god and excited crowds into a state of hysteria. Her healings were widely documented and there was never any evidence of fraud. She was one of America’s first female evangelists, which brought her hardship in some ways but made her very popular in others…Her sermons preached a conservative gospel but used progressive methods. They were incredibly visual and at times would have a company of 450 people performing her sacred operas or dramatic bible re-enactments. She wanted to avoid the usual church service that she felt people were just going to out of duty and wanted to compete with popular entertainment such as vaudeville and the movies, keeping the message serious but told in a light-hearted way. She didn’t hesitate to use the “devil’s tools'' to tear down the devil’s house. She was an American phenomenon, more than just a household name. I found it hard to find the balance between these 2 completely different women—the sinner and the saint, but it all makes sense when you take into account the era and what was happening socially in New York during that time. These women, including Reno, were in their prime in the 1920s, a decade where everything was being turned upside down, especially for women.

The original Broadway production made a star of Ethel Merman, the actress portraying Reno and she would go on to repeat the role in the 1936 film version. Since its debut, the musical has been revived several times in the United States, England, and Australia.

Woman of the Rock (1949)

Hector Chevigny’s novel, Woman of the Rock follows a PR man named Herb Wallace who has been asked to read the secret autobiography of one of his former clients, Los Angeles evangelist Ruth Church. Church has recently passed away and her final request is that the manuscript she penned be published upon her death. Church leaders, however, are hoping to destroy the manuscript as revelations in her story might be seen as antithetical to the wholesome image she projected. As Wallace begins to pore through the manuscript he starts to flashback to the time he worked for Ruth and the church she founded, God’s Own Temple in Santa Monica. As one might expect, Ruth is an exceptionally charismatic woman of faith who mysteriously disappears one afternoon while on an evangelical tour. We learn that Ruth was growing weary of being placed under the figurative microscope and began a flirtation with Arthur, a man working in her church. Arthur proposes that Ruth run away with him to Seattle, an appealing prospect for a woman who is growing increasingly weary of endless responsibilities and invasive handlers controlling her every move.

The fact that the Ruth Church was based on Aimee Semple McPherson was not lost on audiences or critics. In a review written for the Hartford Courant, writer Frances Hunter wrote that “we are made to feel that the author, rather than creating fictional characters, is trying to justify and explain the acts and emotions of Aimee Semple McPherson...” while the Vancouver Sun wrote that “You wouldn’t have to be gifted with second sight to know that when Hector Chevigny wrote Woman of the Rock he had none other in mind but the flamboyant Amy Semple McP.” Strangely, the Los Angeles Times review of the book chose not to make any direct mention of Aimee, instead writing cryptically that “the parallel of Ruth Church’s story with the career of a well-known evangelist in real life is obvious, although the author has embellished the familiar facts with a good deal of fiction.” No doubt Aimee’s passing four years earlier, was still fresh on the minds of many Angelenos and the critic had the good taste not to drop her name. The review did specify that the book “portrays Ruth with sympathy, revealing her doubts as well as convictions, her frustrations as well as her triumphs. There is no attempt to judge her actions, private or public.”

"The Ballad of Aimee McPherson" (ca 1961)

"The Ballad of Aimee McPherson" is a folk song about Aimee’s disappearance that gained some notoriety when it was recorded by American folk singer Pete Seeger. The song’s provenance is muddy: Seeger did not write the song but the albums on which it appeared credit folklorist John Lomax Jr. as the source. It’s not clear if Lomax wrote the tune or simply collected it as part of his work. The song plays fast and loose with some of the facts but is meant to be tongue in cheek, taking the side that Aimee did run away with Kenneth Ormiston to Carmel.

Did you ever hear the story of Aimee McPherson?

Aimee McPherson, that wonderful person,

She weight a hundred eighty and her hair was red

And preached a wicked sermon, so the papers said.

[Chorus]

Hi dee hi dee hi dee hi

Ho dee ho dee ho dee ho.

Aimee built herself a radio station

To broadcast her preaching to the nation.

She found a man named Ormiston who knew enough

To run the radio while Aimee did her stuff.

She held a camp meeting out at Ocean Park

Preached from early morning 'til after dark.

Said the benediction, folded up her tent,

And nobody knew where Aimee went.

When Aimee McPherson got back from this journey,

She told her tale to the district attorney.

Said she'd been kidnapped on a lonely trail.

In spite of all the questions, she stuck to her tale.

Well, the Grand Jury started an investigation,

Uncovered a lot of spicy information.

Found out about a love nest down at Carmel-by-the-Sea,

Where the liquor was expensive and the loving was free.

They found a cottage with a breakfast nook,

A folding bed with a worn-out look.

The slats were busted and the springs were loose,

And the dents in the mattress fitted Aimee's caboose.

Well, they took poor Aimee and they threw her in jail.

Last I heard she was out on bail.

They'll send her up for a stretch, I guess,

She worked herself up into an awful mess

Now Radio Ray is a going hound;

He's going yet and he ain't been found.

They got his description, but they got it too late.

Sin they got it, he's lost a lot of weight.

Now I'll end my story in the usual way,

About this lady preacher's holiday.

If you don't get the moral then you're the gal for me

'Cause they got a lot of cottages down at Carmel-by-the-Sea.

The Day of the Locust (1975)

The female evangelist, “Big Sister,” in John Schlessinger’s 1975 film The Day of the Locust, does not appear in Nathaniel West’s landmark novel of the same name. The character of “Big Sister” is a product of screenwriter Waldo Salt’s imagination that grew out of the tortured prose of West. Brought to life by the finest actress of her generation, Geraldine Page, the similarities between “Big Sister” and Aimee are readily apparent: white satin robes, neatly bobbed hair, and bigger than life personality. Big Sister is a charismatic charlatan who provides little help or solace to the downtrodden and, instead, gives us the fatuous showmanship that mirrors the rest of Nathaniel West’s Los Angeles. Big Sister is yet another symbol of the phony glitter of 1930s L.A. and the character is less of a critique of Aimee Semple McPherson than it is of the town she called home.

The Disappearance of Aimee (1976)

One of the first films to directly portray Aimee Semple McPherson and events surrounding her disappearance was the television film, The Disappearance of Aimee (1976). The television film originally aired on the NBC network in November as part of the Hallmark Hall of Fame franchise and was based, in part, on the actual transcripts of Aimee’s prosecution by Asa Keyes. The production, directed by Anthony Harvey (The Lion in Winter), hasn’t been commercially available for decades but has become notorious thanks in part to an all-star cast that didn’t get along. The film stars Faye Dunaway as Aimee, Bette Davis as her mother, Minnie Kennedy, and a young James Woods as an Assistant D.A. The plot of the film is focused solely on Aimee’s disappearance, reappearance, and failed prosecution. Dunaway, who would win a Best Actress Oscar for Network (1976) in a matter of months following the telefilm’s premier, is magnetic and properly enigmatic. In her autobiography, Dunaway wrote,

“It was one of those stories that you fall in love with if you’re an actress. A strong, charismatic woman, caught in a web of intrigue, perhaps of her own making. There was love, lust, politics, religion, and a domineering mother, all the stuff that makes for great drama, a kind of Greek tragedy set in Southern California.”

In this story, Aimee is the obvious protagonist and there are touches of second-wave feminism throughout. The film does not disclose “what really happened” but does make it clear that this very public woman needed one moment in time that belongs solely to her and no one else. It’s a vivid reminder that, when all is said and done, Aimee was a human being.

Davis, as always, is superb as Aimee’s mother; in many regards she represents public interest in the case, demanding that Aimee reveal the truth only to be stonewalled. Years later, the film would come back into the public sphere when a post-stroke Davis visited the Tonight Show and bemoaned her experience working with Dunaway. She would repeat her grievance on several talk shows and in her autobiography where she also confessed that she had wanted to play Aimee while a contract player at Warner Brothers in the 1940s:

“I had seen the evangelist once at the Foursquare Gospel Church, had heard her on the radio many times, and had begged for years to be allowed to play her. At the time no studio would touch the story; the censors would never permit a film about a woman who was the head of a church and was also a whore. So I ended up later playing her mother.” Although difficult (but not impossible) to view the telefilm at present, the production is top-notch and is likely the best film directly about Aimee Semple McPherson that has been made thus far.

Aimee! (1981)

1981’s Aimee! was, perhaps, the first time McPherson’s story was brought to the stage as a musical. With lyrics by Patrick Young and music by Bob Ashley, the production was staged in McPherson’s home country of Canada. The play premiered at the Confederation Centre of the Arts in Charlottetown on Prince Edward Island and featured actress Maida Rogerson as Aimee. The production does not appear to have toured Canada nor does it appear to have crossed the border into the United States at any point. Reviews for the production suggest that the show focused on “a slightly embarrassing story” (i.e. her disappearance) and while reviews were not altogether unkind, this production was far from groundbreaking. A review in the Calgary Herald wrote that “As a musical, Young and Ashley in their first joint work for the Charlottetown festival have recalled the times more than the life of Aimee.”

Bright Young Things (2004)

Bright Young Things is a film adaptation of Evelyn Waugh’s Vile Bodies directed by actor Stephen Fry. In this film, Mrs. Ape appears in just three short, mostly forgettable, scenes but she is brought to life by actress Stockard Channing. Channing has a prolific career on both stage and television with multiple awards to her name but, to her own dismay, is probably best known as Rizzo from the film Grease (1978). Channing doesn’t get a chance to make much of an impression in this part and there is very little to tie it back to Aimee other than the fact that McPherson was identified as the model for this particular character long ago. The only plot change is that the Angels get less face time than they did in the novel and Mrs. Ape is outraged by having her name appear in Barclain’s libelous column instead of using it to her advantage the way she does in Waugh’s novel.

Scandalous: The Life and Trials of Aimee Semple McPherson (2012)

Scandalous represents the second time Aimee’s life was put to music. Its pedigree is truly strange—the music and lyrics were penned by talk show hostess Kathie Lee Gifford and the primary financier was former Education Secretary and Amway heiress Betsy DeVos and her husband, Dick. A New York Daily News report indicated that the Foursquare Church (the church Aimee founded) had also invested two million dollars in the project, all of which was lost when the show folded. The musical had been a passion project for Gifford who had been working on it for over a decade and retooling it in workshops since 2005. The musical covered everything from Aimee’s childhood to her cross-country road trip to her disappearance and prosecution. Carolee Carmello, the actress who played Aimee, was unanimously praised for her performance and earned a Tony nomination for Best Actress in a Musical but Carmello alone couldn’t save the production. Near the close of the show, The New York Daily News sniped that “[Gifford’s] show about Aimee Semple McPherson, an evangelist nobody knows, never ignited interest.” Whatever the reasons for the show’s failure, it is notable that it didn’t come anywhere near Los Angeles. Scandalous went through workshops and previews in Virginia, New York, and Washington before moving to Broadway where it closed after three weeks. I can’t help but wonder if the denouement might have been different had it played in Los Angeles where Aimee is entrenched in our civic history.

Sister Aimee (2019)

Samantha Buck and Marie Schlingmann’s 2019 film focuses on Aimee’s disappearance as she makes a hasty decision to run away with Kenneth Ormiston (or “Kenny”) in response to burnout from being in the public eye. Hoping to write a book on a legendary Mexican desperado, Kenny proposes that the pair run away to Mexico so he can conduct research and, imagining some sort of escape from her demanding life, Aimee agrees. When taking the main roads proves to be difficult because of Aimee’s celebrity, Kenny hires a guide to escort the pair along the back roads. The couple is surprised to see that their guide is a petite Mexican woman named Rey. Like something out of a Spaghetti western, Rey is a bit of a taciturn and turns out to be unusually skilled with weapons. As the story unfolds, Kenny slowly morphs into a whiny man-child, causing an assortment of problems for the trio. The two women, on the other hand, demonstrate strength and resourcefulness that prove to make the story compelling. The story comes to a climax with what appears to be an allusion to Mexico’s Cristero War when Mexican police find Aimee’s robes and cross and arrest the trio. Aimee’s efforts to free the trio from jail remind her that her true calling is to be in front of an audience.

The directors have done a lot with a slim budget and the movie is beautifully photographed, well-acted (particularly Anna Margaret Hollyman as Aimee), and, more importantly, it has a great sense of humor. Considering how far the film strays from the known facts, it’s curious that the filmmakers decided to name the character Aimee Semple McPherson instead of a pseudonym or a fictional identity of some sort. While at the preface of the film, the filmmakers do state outright that the events that follow are fictionalized, it would have been just as easy to change character names to eschew any criticism. Still, on its own terms, the film is quite enjoyable and benefits from a fresh perspective as this is, quite likely, the first film about Aimee to be made by women. Reviewers have pointed to a queer sensibility between the two female characters and it's likely there for those who are looking for it but it’s hardly overt; still, it will probably bother those who regard Aimee’s legacy as untouchable. A goodbye kiss that is thematically reminiscent of the one at the end of Thelma and Louise (1991) is likely to inflame such sensitivities. Ultimately, the film tells us that Aimee Semple McPherson was an independent woman who had agency over her own life.

Penny Dreadful City of Angels

After canceling Penny Dreadful, its Victorian-era gothic horror series, the Showtime cable network decided to revive the franchise with a slightly different focus. Canceled after its first season, Penny Dreadful City of Angels is an interesting but convoluted mish-mash of stories dedicated to Los Angeles of yore. The show skirted Mexican American culture, syncretic spiritualism and managed to incorporate fictional versions of true events—everything from the Pasadena freeway to Nazis in Los Angeles and what appears to be the Zoot Suit Riots thrown in for good measure. Almost none of the characters in the series seem to be based on historical figures except that is, for Sister Molly Finnister (Kerry Bishe) the singing evangelist. Molly is clearly based upon Aimee Semple McPherson but is, perhaps, the most anemic version of Aimee to manifest in any medium. Like Aimee, Molly leads a congregation (in this case the Joyful Voices ministry) from a grand church (the Pasadena Civic Auditorium standing in for an Angelus Temple prototype) that has its own broadcasting station. Curiously, Molly sings pop standards rather than spiritual hymns at her services but faith healing and charitable contributions are an integral part of her work. Dominated/suffocated by her mother, Sister Molly longs to have some degree of anonymity but her position in the community makes that impossible. Molly begins an affair with the Mexican American detective investigating the murder of a high-ranking church member and we see Molly’s loneliness and internal conflicts as her story progresses. The show failed to be renewed for a second season but the final episode kills the character of Sister Molly through a suicide. The disconnect between Sister Molly and Aimee is patently obvious as Molly lacks the charisma that Aimee had in spades and Molly’s passive nature renders her bland, something Aimee would never be accused of being.

Perry Mason

Decades after both Erle Stanley Gardner’s novels, Warner Brothers serials, and Raymond Burr made Perry Mason a household name, the stalwart Los Angeles lawyer made a comeback on HBO. This incarnation returns Mason to 1930s Los Angeles and has an assortment of subplots and characters that echo touchstones within Los Angeles history. In season one, Mason crosses paths with a charismatic female evangelist from Canada, Sister Alice McKeegan. Sister Alice is the platinum-haired founder of the phenomenally popular church, the Radiant Assembly of God, and is brought to life by actress Tatiyana Maslany (Orphan Black). Sister Alice lives under a microscope and the weight of a life she seemingly has had no choice in living seems to ensure that she is on a path to a breakdown. Alice’s mother tells her “...you are the Assembly. You are the Temple. You are every cornerstone laid for every church chapter we build.” Alice’s response to that statement is “Don’t say that. Even if it's true. It’s not helpful to hear.” After suffering a seizure during one of her sermons, Alice has a vision that she is meant to perform an impossible miracle one Easter Sunday. When that miracle seems to have materialized, a stunned Alice runs away and, seemingly, disappears from her life.

The character of Sister Alice, in some respects, feels like she has been shoehorned into the story and feels more like she is a means for the title character to confront his own existential crisis. Mason’s experiences in WWI have resulted in profound PTSD and he spends the season questioning the meaning of his life. In one scene he tells Sister Alice “God left me in France, Sister.” She immediately counters that statement, telling him that “God is with you whether you acknowledge him or not.” In their final scene together, Alice leaves Mason with some spiritual food for thought. Perhaps the most obvious disconnect between Sister Alice and Aimee Semple McPherson is that Alice chose to run away from the life that she was just tired of living; Aimee, on the other hand, embraced her role as a spiritual leader and maintained an unwavering sense of righteousness throughout her lifetime.

Other notable mentions:

An Evangelist Drowns (1926)

Upton Sinclair’s poem about Aimee’s (presumed) drowning.

Hooray for Hollywood (1937)

A Johnny Mercer/Richard Whiting song written for the Busby Berkeley film, Hollywood Hotel. Aimee’s name is mentioned in the original lyrics sandwiched in-between child star Shirley Temple and Donald Duck.

Woman of the Rock (1950?)

According to William Romanowski’s book, Reforming Hollywood, Citizen Kane screenwriter Herman J. Manckewicz adapted Hector Chevigny’s 1949 novel for the screen. Hollywood columnist Hedda Hopper declared the screenplay to be one of the “hottest scripts of the year” but the production code ultimately forbade the movie from being filmed.

Jim Morrison’s Adventures in the Afterlife (1999)

The publisher’s description for Mick Farren’s satirical book reads as follows: “Jim Morrison's Adventures in the Afterlife picks up the story of Morrison as he hurtles through a purgatory-like afterlife in search of some way to bring his soul to peace. Along the way he finds Doc Holliday—and together they find themselves chasing the restless fire-and-brimstone evangelist Aimee Semple McPherson, whose soul has broken after death into two warring halves. McPherson's sexier half becomes the object of Jim's obsession, and as the two struggle to find each other in this disordered land, their wild, careening chase through a dozen dystopiae recalls imagined worlds as diverse as Burgess's A Clockwork Orange or Terry Gilliam's Brazil.”

Sister Aimee: The Aimee Semple McPherson Story (2006)

A feature film by Richard Rossi starring Mimi Michaels. Rossi also directed a documentary on Aimee entitled Saving Sister Aimee.

An Evangelist Drowns (2008)

An Evangelist Drowns is a one-woman play written by Professor Gregory Thompson that premiered at Rogers State University and starred student Mariah Owen. The title is borrowed from the Sinclair poem.

Given all that Aimee Semple McPherson has inspired over the past century, it's indefensible to make the statement that she is a person that “nobody knows.” Thanks, in part, to a few lost weeks, Aimee has surpassed her earthly accomplishments and has graduated to a bonafide pop culture phenomenon residing in the recesses of the public imagination. While Aimee Semple McPherson may have passed away in 1944, the idea of Sister Aimee, the charismatic female evangelist is alive and well and, more importantly, weaved into the folklore of the City of Angels. This Sister Aimee has evolved into a blank slate for novelists, filmmakers, playwrights, songwriters, and more to project ideas about things like faith, humanity, compassion, corruption, gender, and women’s roles in society. For a person that “nobody knows” Sister Aimee certainly has been busy making herself known for the past 100 years.