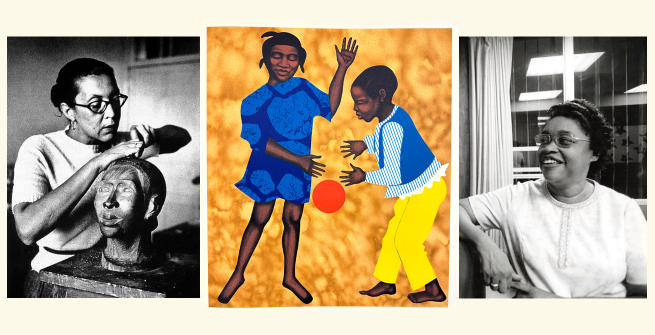

In honor of World Poetry Day, I would like to bring attention to, of course, a poet, Margaret Walker but also a sculptor and artist, Elizabeth Catlett, and a book that features the two women’s creative styles—For My People. This 18-1/2 x 22-1/2 inch book is a limited edition and one of 400 copies, featuring six vibrant lithographs by Elizabeth Catlett on 100% cotton Arches Cover paper, and it is housed in the Central Library, Special Collections. The artistry of the book is absolutely stunning, more importantly—the way they managed to take the horrors of racism and oppression, the pridefulness of unity and revolution, and intricately woven beauty in and out is remarkable. Interestingly enough, the author and illustrator were once roommates at the University of Iowa in 1938 (with Walker coming in 1939), fast forward to 1992, For My People is published, creating this full circle moment between the two. It is hard not to think of the genius that is Margaret Walker when discussing Black women in literature or the intellectualism of Black culture. Likewise, it is almost impossible not to mention or hear the name Elizabeth Catlett when dissecting the identity of the African American woman or the social climate of oppressed peoples—mainly African Americans and Mexicans. Both women are able to encompass the harsh realities within the Black community and create not only art but art done in such a soft, eloquent, and profound way.

I noticed a recurring theme in Margaret Walker’s writings and interviews: Heroism. The identity of the hero is everywhere in Walker’s work, and when she speaks—why? Perhaps the injustice of their life bothers her, or the simplicity in speaking their names, so the world never forgets. Walker once said of heroes: “What greater price can you pay for heroism? Who can you think of that deserves to be a hero who has not given his life for what he believes?” These two extraordinary women may not have given their lives in the way it, unfortunately, meant for many others, but they used their life and career to be a voice. They made sure the heroes before them were never forgotten, created images that were intended to evoke thought, and made sure their audience saw what needed to be seen—what was important for humanity and integrity. Walker had a wonderful quote in which she is referencing the integrity between Black and White: "I don’t think there is anything sacred in the integrity of race, white or black." "...our culture is neither black nor white but…a synthesis of the two. The white man and the black man are still fighting over their racial integrity or entity when it doesn’t exist anymore." The art and messages of Catlett and Walker reach far beyond the annual mundane and recycled realms of February.

Where many artists attempt to depict a beauty in Black struggle, Catlett and Walker correctly locate that beauty in our moments of resilience. Examples of this polarity can be seen in the book - Walker’s ability to create this wave-like existence in her words by describing a simplistic beauty of Black life; joy, love, worship, and then sending it all crashing down with harsh realities of murder, oppression, and dehumanization. Catlett’s art mimics this wave by delivering vibrant, mesmerizing pieces in which she hides (or does she even really hide it) powerful and painstaking window peeks of black reality. Art is humanity’s greatest tool for insight. It provides imagery to the portrayal of a story and, more importantly, creates conversation. Walker and Catlett existed through a time when the Black struggle had reached another momentous peak of revolution (Ex. Black Panther Party, the Vietnam War, the assassination of both Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, and the arrest of Angela Davis). Catlett used her art to express her sentiments about Civil Rights and the injustice towards working-class people. One of my favorite pieces of hers is titled Black Unity—a double-sided sculpture; one side displays a fist—also known as the Black Power salute, a gesture often used by African Americans to symbolize black liberation and unity—the other side displays two African tribal mask-like faces (this piece was displayed in the Brockman Gallery Archive—also housed in the Special Collections Department—a Los Angeles based gallery opened by brothers, Dale and Alonzo Davis during the late 1960s).

Catlett made political statements through her work; she advocated for Angela Davis’ freedom during her very publicized arrest, wanting to bring awareness to not just Davis but all political prisoners. Walker, who was born in rural Birmingham, Alabama, credits the nature she was brought up around during her childhood as the inspiration behind not just many of her pieces but her ability. She also traveled once with a radical and bohemian group across the states, writing what she cites as her “very best poetry”. Not as politically charged as Catlett, Walker wrote many poems about later Black revolutionaries, like Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglas. One such riveting poem is from her book, October Journey titled "Harriet Tubman"; in it, she writes:

Dark is the face of Harriet,

Darker still her fate

Deep in the dark of Southern wilds

Deep in the slavers’ hate.Fiery the eye of Harriet,

Fiery, dark, and wild;

Bitter, bleak, and hopeless

Is the bonded child.Stand in the fields, Harriet,

Stand alone and still

Stand before the overseer

Mad enough to kill.

Another interesting moment between these two women is the fact that they both have pieces of work on Harriet Tubman. Catlett has multiple lithographs of her, that she improved on over the years. While Walker would have viewed herself as primarily a humanitarian, she also acknowledged the way that intersectionality shaped her experiences. Through these two women’s art, they offer us a tour of their minds and the things they lived through.

In a conversation with poet Nikki Giovanni, Margaret Walker describes her poem "The Ballad of the Free" as being better executed than her poem "For My People"; this is where I respectfully disagree. "For My People" is actually a beautifully crafted piece that paints a painful image of Black struggle. It is sorrowful, yet her words are filled with pride, and for the reader, provide the atmosphere of simply being seen and related. Walker takes the reader on a turbulent ride of joy and pain with stanzas like:

For the boys and girls

who grew in spite of these things

to be man and woman,

to laugh and dance

and sing and play and drink their wine

and religion and success,

to marry their playmates and bear children

and then die of consumption

and anemia and lynching;

This stanza is important because it can be nostalgic for many, and it brings a sense of light-heartedness and then steals that from you with what was the outcome for many—death. The realization that happiness is only momentary and death—via the most unfavorable of ways is lurking and plotting. Catlett was able to mirror this feeling with her artwork. She painted us in the most vibrant of colors, larger than life. In some lithographs, you can even see the African influence used when drawing the faces—resembling that of African tribal masks. Walker acknowledges the hardships and pointless lessons that led to inescapable truths:

For the cramped bewildered years

we went to school to learn

to know the reasons why

and the answers to and the people who

and the places where and the days when,

in memory of the bitter hours

when we discovered

we were black and poor and small and different

and nobody cared and nobody wondered

and nobody understood;

Despite the wave of emotions one goes through while reading this book, collectively, it is a masterful piece that showcases not just the artistry of both Walker and Catlett but their daring to speak on African Americans in the truest light. This book is celebratory in ways that are outside its content of it. Two African American women who dared to have a voice and use it for the betterment of their people and serve as inspiration for many others alike.

In essence, there is much more that can be said about For My People and the heroism displayed by both author and illustrator. Instead, I leave you with a poem by Margaret Walker from her book October Journey titled "Ode on the Occasion of the Inauguration of the Sixth President of Jackson State College":

"Ode on the Occasion of the Inauguration of the Sixth President of Jackson State College"

I.

Give me again the flaming torch of truth

that burned before the altars of our gods;

the spirit nascent, sleeping on the breasts

of black men born to die on foreign shores

on battlefields, and on familiar trees

hanging with bloody forms and blackened bones

kindled to death by lynching mobs.

I burn to bring you words from oracles

from temple fires and smoking flambeaux

snatched from hands of running warriors;

to speak the fiery words of bronzed and sepia men

whose broken threads of time

were cut before their prime

the primitive and halcyon days

before the shame of slave ships brought black men here

to sacred lands of red men

and changed them into whitened sepulchers of hate.

Dark were the years

that spawned three centuries of toil and trouble

deep in this southern land

before our fathers heard of liberty

and learned that freedom did not come

when chains of bondage fell from shackled limbs

and not from minds and hearts

still chained in ignorance, and circumscribed by prejudice and hate.

For days like these we need the truth.

We need the shower-washing deluging of truth.

Beneath the slavers’ rod

chastisement of the soul

the brutal lashing of the mind

the whip of ignorance.

Broken but not demented by the charge

of mental shock and cruelty.

Offended by outrage

but never blown apart by bitterness.

Record the day when millions of our kin went free

to wander homeless in a devastated land

against the hostile wrath of brutish men

sullen and sulking in defeat

yet mired themselves in darkest ignorance.

Was it the dove of peace

bearing the twig of olive in her beak

that wrought a miracle?

Or was it phoenix bird of poetry

Winged Pegasus that lifted high the dream

to mountain height and bade the black and unknown

bards

express their longing for the truth?

Perhaps, instead, the eagle eye

of money and greed for gold and land

lifted her face first to freedom’s hallowed light

while Justice, blind, was balancing the scales

and Truth was bleeding on a cross of shame.

This place of learning came instead

from humble men,

and Education shone its rays upon

weak vessels of the Lord

born in a House of Prayer

and in the consciences of Christian hearts

this place we call a College was first conceived.

II.

Up from the Mississippi soil

her sons and daughters came

from red-clay hills and delta land

the coastal plains

from barren rocks, from loam and sand

they came with hunger for the truth

for knowledge and the need to understand

the meaning of our living in this southern land.

And so he came

fresh from the war

a war fought, too, for liberty

as all wars, so they say, are fought

and like all black men living in America

he came without the heroes’ welcoming

as all black men returning home from foreign wars

to make the world safe for democracy

eo end all wars

to give us freedom, life, and liberty

as all black men

have found the hope of truth

turn ashes in the mouth.

And like his people

symbols of the land

he found the high tides of his destiny

our destiny, one people and one man

wh seek a free and noble land

a nation high with destiny, with promise unfulfilled

a race of men who can

yet make the dream come true

now in this time of truth

a people hearing universally

a Cry for freedom ringing in this land

The hands of destiny now mark this clock of life

and after time, a hundred years now passed

searching for freedom is our destiny

that all men everywhere may see

the blinding face of truth

and thus may know

and knowing may be forever free.

III.

O bird of paradise,

bird of the wilderness

cardinal bird of truth

now sing the song I long to sing

the song of hope and love

pride in our past

faith for our future

and hope undimmed by all our ancient fears,

Sing now a paean for this rising man

a prayer breathed on the wings

of shifting winds

that search the world

and bring the storm of change into our land.

Now steady one man’s hand

and may the winds of fate

be neither harsh nor rude.

Sing birds of paradise,

bird of the wilderness, now sing!

Interview with Angela Charles about the book, For My People