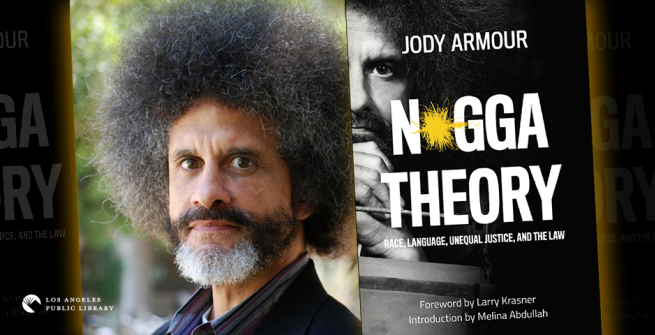

Jody David Armour is a professor at the USC Gould School of Law. He has been a member of the faculty since 1995. Armour’s expertise ranges from personal injury claims to claims about the relationship between racial justice, criminal justice, and the rule of law. Armour studies the intersection of race and legal decision making as well as torts and tort reform movements. His latest book is N*gga Theory: Race, Language, Unequal Justice, and the Law and he recently talked about it with Daryl Maxwell for the LAPL Blog.

What was your inspiration for your new book?

There were two driving inspirations for my book. The first inspiration was the memory of my dad, an indomitable jailhouse lawyer who found the key to his prison cell in the warden’s own law books. Using those books, he taught himself the law, wrote his own writs of habeas corpus, and represented himself pro se all the way up to the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, where he triumphed in a case I now teach my criminal law students called Armour v. Salisbury. His example taught me at an early age the power of language to deliver black bodies (like his) from bondage and inspired my reflections on the nature and power of words and symbols throughout the book. In fact, one reason I deploy the N-word throughout the book is to provoke constant reflection on the power and stakes of words and symbols.

Another inspiration has been the Black Lives Matter movement and its insistence that real racial justice can only come from rattling the foundations of the status quo. In that spirit, my book radically critiques three cornerstones of the status quo in criminal matters—namely, conventionally moral, legal, and political theory. The book’s complete rejection of respectability politics in matters of crime and punishment was also inspired by the utter rejection of such politics by BLM activists. It seeks to provide a new moral, legal, and political theory that supports BLM demands to defund the police and abolish prisons.

A final inspiration has been black artists, writers, and performers (from the Last Poets to Pac, Nas, Cube, and Hov to Dave Chappelle) who have taken the N-word, a blood-soaked epithet often used to vilify and wound and used it as part of a discourse of resistance.

The title you’ve chosen is a bit shocking and potentially problematic. While I know this is the name of the theory on which you’ve been working for years, are you at all concerned that the title may keep people from reading your book (especially the ones who may need the most to read it)?

I grappled with this very question long and hard before committing to using the N-word in my title. The N-word in the title and throughout the body of the book will undoubtedly deter some from reading my book (including some who may most need to). Like the NAACP N-word abolitionists, I describe in the book, some blacks and non-blacks alike view the word as a form of hate speech with a fixed and frozen meaning that renders it useless or counterproductive in progressive political communication and creative expression. I regret losing these readers. But I have to weigh the costs of the title against its benefits, which include:

- It’s a disruptive word, and in that sense, it chimes with a core tactic of Black Lives Matter, namely, disruption, cutting through our complacency by, for instance, crashing Sunday brunches in genteel tree-lined neighborhoods and reciting the names of black victims of state violence... the N-word disrupts the calcified language of the academy;

- N*gga Theory is a theory not only about the kinds of persons the N-word is often used to denigrate and condemn, but it is also a theory about the word itself, as a word, that is, as an example of linguistic symbolic communication whose meaning is not fixed and frozen but mutable and hotly contested by black artists and writers seeking to define their social identity and vindicate their social existence;

- I use the word as performative art, in the spirit of N-word virtuosos such as Pac, Nas, Cube, and Hov, artists who used the word both as part of their disruptive and critical creative expression and to promote black solidarity, including solidarity with violent black criminals;

- Precisely because of its disreputably profane form and association with “gangsta rap,” an art form that especially offends proponents of respectability politics, the word signals my rejection of respectability politics and support for politically progressive gangsta rap;

- This book seeks to humanize the most demonized, monsterized, otherized Americans, violent black criminals, and when used as an epithet, no word in the English language more otherizes its referent than the N-word.

No other title succinctly captures these layers and nuances. I’ve had a number of readers tell me that at first, they felt a reflexive and understandable discomfort with the title but that after reading the book they couldn’t imagine a title more apt for this project. I hope other uncertain readers overcome their reservations and give the book a chance to prove that the unparaphrasable power of the N-word to promote unique insights into the relationship between law, language, morality, and politics justifies any initial discomfort about my deployment of it.

How long have you been researching Critical Race Theory? How long did it take you to write the book?

I’ve been researching Critical Race Theory since I entered the legal academy in the 90s. My first law review piece appeared in the Stanford Law Review and analyzed the role of race in self-defense cases, arguing that even though technically the racial identity of an ambiguous figure or supposed assailant IS legally relevant in a self-defense case, courts should do all they can to prevent shooters from pointing to or playing on race as a factor in their assessment of the dangerousness of black victims of their use of deadly force. My next article appeared in the California Law Review and was one of the first in the legal literature to connect anti-black bias in the cognitive unconscious to the legal decision making of jurors, judges, and lawyers in civil and criminal cases. The brand of Critical Race Theory I call Nigga Theory first came into being in 1999 at an annual American Association of Law Schools gathering of tweedy law professors at which, to disrupt and provoke uncomfortable conversations (core tactics of today’s BLM activists), I spontaneously spit 16 bars of N-word-laden gangsta rap (Cube’s “Nigga Ya Love to Hate”) in my formal address to my staid and dignified colleagues. Nigga Theory then took the form of a play about mercy for violent black criminals that I wrote in 2008 titled Race, Rap, and Redemption. It took about five years to research, write, and workshop my book’s core discussions of legal theory, moral theory, ordinary language philosophy, unconscious bias, political science explanations of Trump’s 2016 election results, the politics of respectability in criminal matters, and the death penalty.

What was the most interesting thing you’ve learned from your research? The most surprising or unexpected thing you’ve learned?

The most interesting thing I’ve learned from my research is that morally we are at the mercy of luck; the “self” we take so much pride in is no more than a tissue of contingencies.

The most surprising thing I’ve learned is that criminals are not discoverable facts of nature that fact-finders merely find, rather, they are socially constructed figments of jurors’ bias-ridden mental processes. Murderers, for instance, are minted and manufactured in criminal trials; they are reflections of a jury’s moral judgments, which can be riddled with irrationality and racial bias.

The publication of your book could not be more timely. Acts of social and political unrest had happened sporadically in Los Angeles in previous decades. Why do you think so many different protests happened in Los Angeles during the 1960s and continued into the early 1970s?

So many protests happened in LA during the 1960s and continued into the early 1970s because, like many other metropolitan areas in America, LA chose to address crime problems associated with grinding poverty and savage social inequality with police and jails rather than with crime prevention in the form of adequate spending on housing, health care, food, education, and a guaranteed basic income for all residents of all races. We made jails and prisons the receptacles of our social and policy failures and put police in charge of occupying, containing, and controlling racially oppressed populations (through policies such as Broken Windows policing); we also put them in charge of arresting and locking up the foreseeable consequences of the criminogenic conditions to which we consign many blacks, namely, blacks who commit serious crimes. Putting police and jails at the center of your poverty governance and crime prevention policy creates a reservoir of resentment in many black communities toward these state actors, many of whom are racist and corrupt to boot. This creates an urban powder keg, and every friction-filled encounter between police and black citizens has the potential to spark another urban conflagration.

Do you see any parallels between the Los Angeles protests of the 1960s and the current political unrest/protests? Any major divergences? Are you surprised that, 50 years later, many of the same issues are still being protested?

When you juxtapose the racial injustices and festering frustrations that drove the unrest of the 1960s and those behind the current political unrest and protests, you see with excruciating clarity that, in many respects, ain’t nothin’ changed but what year it is!? Sure, there are some differences, but they pale to insignificance in comparison to the abiding similarities. Anti-black policies and practices in law enforcement, employment, housing, education, and health care are not bugs; they are features of the American way—they are baked into our basic social arrangements and reinforced by widespread conscious and unconscious racism in state actors and ordinary people. In a recent book review of N*gga Theory, the critic observed that although my first book, Negrophobia and Reasonable Racism: The Hidden Cost of Being Black in America, was published in 1997, it could have been published last week, for the same racial justice issues I analyzed then are the ones roiling America now. When your analysis focuses on root causes, pervasive patterns, and unexamined assumptions, as mine does, it can remain relevant despite the march of time. Just as once a thief is caught, a whole string of crimes can often be solved, once certain basic misconceptions about morality, law, language and politics are exposed, a whole string of racial injustices can be resolved in a way that delivers us collectively from this unrelenting Racial Injustice Groundhog Day of videos, hashtags, racial unrest, and cell blocks brimming with black bodies.

What’s currently on your nightstand?

Afropessimism by Frank B. Wilderson III.

What was your favorite book when you were a child?

Elementary: The Little Prince

Middle School: Flowers for Algernon

Was there a book you felt you needed to hide from your parents?

Fear of Flying by Erica Jong.

Can you name your top five favorite or most influential authors?

Toni Morrison

Herman Melville

Ralph Ellison

W. E. B. Du Bois

Frantz Fanon

What is a book you've faked reading?

Tolstoy’s War and Peace.

Can you name a book you've bought for the cover?

The Hundred Wells of Salaga by Ayesha Harruna Attah.

Is there a book that changed your life?

Two: Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison, and Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison.

Can you name a book for which you are an evangelist (and you think everyone should read)?

Down, Out, and Under Arrest: Policing and Everyday Life in Skid Row by Forrest Stuart.

Is there a book you would most want to read again for the first time?

Toni Morrison’s Tar Baby.

What is your idea of THE perfect day (where you could go anywhere/meet with anyone)?

A Juneteenth or Kwanzaa gathering with thousands of other brothers and sisters and cousins and kinfolk in which we celebrate the indomitable spirit of our people and blessings of blackness.

What is the question that you’re always hoping you’ll be asked, but never have been? What is your answer?

Your dad beat astronomically long odds to prevail as a jailhouse lawyer. Is he the most courageous person you ever knew?

He was the second most courageous person I’ve known. The first was his mother, my grandmother, Addie Marion Armour, who somehow and against all odds held everything together in a large family while he languished for years in a prison cell.

What are you working on now?

I’m writing another play about blame and punishment and racial justice that will include rap, drama, cinema, dance, comedy, and other performing arts.