Bourekas (savory stuffed pastry) and shakshuka (eggs cooked in a spicy tomato sauce) are favorite foods for some Jewish people, while knishes (pastry filled with mashed potatoes) and potato latkes (pancakes) are preferred by others.

What accounts for the variety of flavors and names of these dishes? The cultures of Sephardic, Ashkenazic, Mizrahi, and Ethiopian Jews who have resided in diverse parts of the world with access to distinct food sources.

Sephardic Cuisine

Spanish, Greek, Moroccan, and Turkish dishes are prominent in the cuisine of Sephardic Jews who lived initially in Spain and later in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire. Adafina, a savory stew, and huevos haminados, braised eggs, were eaten on the sabbath in Spain. Keftedes (meatballs), the dessert baklava, and dolmades, stuffed grape leaves, are from the Greek tradition.

Morocco also has a sabbath stew called skinha or dafina, as well recipes for couscous with vegetables. Turkish dishes include köftes de prasa, leek meatballs, and börekas or börekitas, a pastry often stuffed with eggplant that evolved from Spanish empanadas.

Ashkenazi Cuisine

The cold climate and impoverished conditions in eastern and central Europe shaped the diet of Ashkenazi Jews. Carbohydrates figure prominently in dishes such as kugel, a baked casserole made with noodles or potatoes, and kasha varnishkes, buckwheat groats with bow tie pasta. The availability of root vegetables gave rise to the beet soup borscht and to tzimmes, a stew that includes carrots and sweet potatoes with dried fruit.

Living in small villages apart from mainstream populations, Ashkenazi spoke Yiddish. Their dishes have Yiddish names, some of which are still in use today: babka, blintzes, gefilte fish, gribenes, knishes, kugel, kneidlach, rugelach, and schmaltz.

Ashkenazi foods such as lox and bagels with cream cheese, dill pickles, and pastrami on rye are delicatessen menu items. There tends to be more familiarity with this type of Jewish food because of the large number of Ashkenazi Jews (over 2 million) that immigrated to the United States between 1880 and 1924.

Mizrahi Cuisine

Mizrahi Jews lived in the Middle East and North Africa over a period of 4000 years and now comprise the majority of the population in Israel. Their cooking reflects the cuisine of the numerous Arab countries they inhabited. Falafel, considered the national dish of Israel, is equally popular in Egypt where it originated, and where it is prepared with fava beans rather than garbanzos.

Mujadarra, a rice-lentil pilaf with caramelized onions, is enjoyed by the Mizrahi as well as by Lebanese, Syrians, Jordanians, and Egyptians. Gondi torshi, meatballs cooked in a soup made with onions, turmeric, quince, beets, dried apricots, and pomegranate juice is an Iranian dish influenced by Iraqi cuisine which arose from the influx of Iraqi Jews in Iran.

Ethiopian Cuisine

A Jewish community has existed in Ethiopia for at least 15 centuries. In the late 1980s and early 1990s, tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews emigrated to Israel. They brought with them the custom of sitting around a large platter from which everyone scoops up spreads and stews using injera, Ethiopian bread made from teff flour. Some of the dishes served are mesir wat (spicy orange lentils); danchi alcha wat (potatoes with carrots); keisar (beets); and doro wat (chicken with hard boiled eggs.

Uniquely Jewish Foods

With so many nations and people throughout the world enjoying foods that are at the center of Jewish cuisine, the question arises: What makes the food Jewish?

First and foremost, the food must be kosher. In simple terms, this means that meat and dairy products are not eaten in the same meal, animals are slaughtered properly, and pork and shellfish are not allowed.

Observant Jews obey the prohibition against cooking on the sabbath. Meals are prepared beforehand, and include a stew that can be kept warm overnight with a low-heat source. Sephardi call this stew “hamin,” from the Hebrew word “hot.” The Ashkenazi call the stew “cholent,” a word that may have come from the French chaud-lent, meaning ‘warm slowly.”

Challah, a loaf of bread made with yeast, flour, eggs, and salt, is served on special occasions including the sabbath and holidays. A blessing over challah is said to express gratitude for this food coming forth from the earth.

Holiday Foods

During the days of Passover, Jews eat matzah, a crisp, flat unleavened bread made of flour and water. This is to recall the hurried exodus from Egypt when there was no time for the dough to rise. Charoset or charoses (Sephardic and Ashkenazi spellings, respectively) from the Hebrew word for clay, is a mixture of fruit and nuts. This symbolizes the mortar used for building construction required by the Egyptian Pharaoh.

For Purim, a joyful commemoration of the Jewish people being saved from annihilation in Persia, treats named after the villain of the story, Haman, are served. The Greek and Turkish version is Haman’s fingers, a cigar-shaped phyllo pastry filled with nuts. Moroccans eat ojos de Haman (Haman’s eyes). Ashkenazi enjoy hamantaschen, triangular fruit-filled cookies shaped like Haman’s hat or pockets. Oznei Haman, Haman’s ears, are thought to have originated in Spain and Italy. They are made of fried dough soaked in syrup or honey.

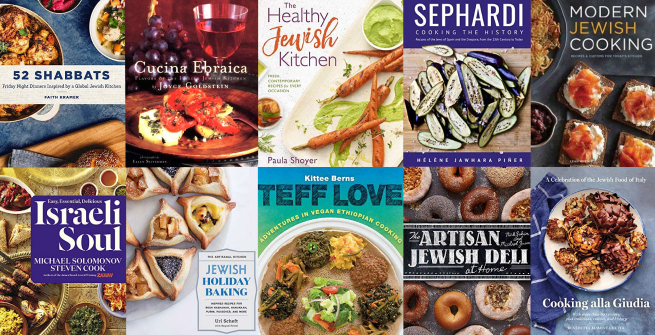

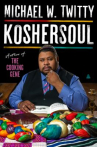

New Directions in Jewish Cooking

Vegan recipes, Jewish and African diaspora cuisine, a cookbook with humor, whole grain natural ingredients, Persian-Iraqi traditions meet the Ashkenazi heritage, and updated traditional recipes are among the Jewish culinary voices of today. May the cuisine thrive and continue!