The growth of the Hollywood branch of the Los Angeles Public Library mirrors the development of Hollywood as a place. From sleepy beginnings, it grew quicker than expected, with highs and lows punctuated by dramatic events and interesting people. The origins of the Hollywood Library date back to the turn of the twentieth century, and its first few decades were well-documented in local newspapers, branch histories, the library’s photo collection, and annual reports. The library, which began before Hollywood was annexed into the city of Los Angeles, has occupied eight locations over the years. We’ll take a look at just a few. The fascinating history of this library includes tales of buildings hauled through the streets of Hollywood (on two separate occasions!), famous patrons, an amazing art gallery, and the ebbs and flows of metropolis building.

The Woman's Club of Hollywood formed in 1905 expressly to bring a public library to the city. Their mission was "the upbuilding of the social, intellectual, and civic life of Hollywood, and its specific and immediate work the establishing [sic] of a public library in the city of Hollywood." In February 1906, the Woman's Club of Hollywood rented two rooms in the VanSyckle Building (on Cahuenga near Hollywood Blvd) and opened Hollywood's first public library. This first location was an independent library (Hollywood was then a municipality) and not part of the Los Angeles Public Library. Miss Ella Gillin was librarian and the sole employee. She kept the branch open 27 days a month (162 hours) with 553 volumes and 203 cardholders.

A special committee appointed by the Board of Library Trustees approached Andrew Carnegie for funds to build a freestanding library. The committee's request was a success. Andrew Carnegie put up $10,000 with the caveat that the community raises additional funds to maintain the library, as well as find a suitable location for the building. Ultimately it was Daeida Wilcox Beveridge, co-founder of Hollywood, who donated land at the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and Ivar Avenue. Moreover, the location was a block from Hollywood's biggest tourist spot at the time, artist Paul De Longpre's studio and gardens. Movers and shakers of pre-film industry Hollywood, including Paul De Longpre, Dr. A.G. Schloesser, businessman Homer Laughlin, and Los Angeles Times publisher Harrison Gray Otis, purchased cash subscriptions to help fund the library.

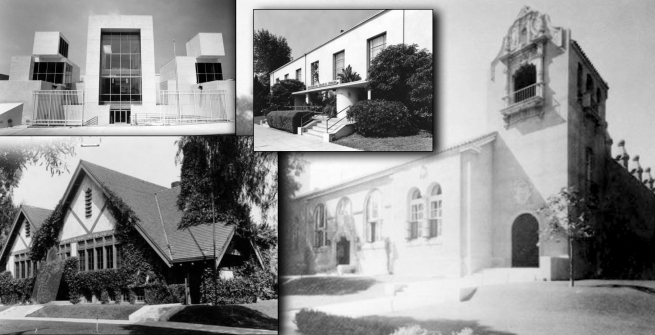

Hollywood Branch Library at 6357 Hollywood Boulevard (1907-1922)

![Tudor Revival style of the original Hollywood Branch located at 6357 Hollywood Blvd [circa 1917].](/sites/default/files/media/images/blog-lapl/2022/Dig_branches/photos_98180_medium.jpg)

Money and land secured, architects Marsh and Russell (Norman Foote Marsh and Clarence H. Russell) designed a building similar to an English cottage with low, beamed ceilings and dark oak woodwork along with dark oak furnishings. Public utilities were invested in the library as well. Pacific Light and Power furnished free lighting, Los Angeles Gas and Electric offered free gas, and Home and Sunset Telephone companies supplied free telephone service. The Woman's Club turned over the new building, located on the northwest corner of Hollywood Blvd and Ivar, to the city of Hollywood on April 1, 1907. The Carnegie library, which opened to the public in May 1907, was embraced by the neighborhood, and the number of cardholders doubled within the first six months. The Woman's Club continued their monthly meetings in the basement (which also doubled as the Children's Room), and the Women's Christian Temperance Union donated a drinking fountain.

Eleanor Brodie Jones, a graduate of the Los Angeles Public Library's training school, became librarian in late summer 1908 as circulation continued to soar and Hollywood had yet to succumb to the movie industry. The rapidly growing city soon had water shortage issues, and Hollywood's citizens voted to be annexed into Los Angeles to help ease their water woes. Annexation meant that the library became part of the Los Angeles Public Library towards the end of Charles Fletcher Lummis' tenure as City Librarian. Following the annexation, the Woman's Club of Hollywood (the group that was the impetus of the library) was told there was no longer enough room for them to hold their meetings in the basement of the library. Lummis tried, unsuccessfully, to create a men's smoking room in the basement. The space, according to the Los Angeles Times, remained a children's area instead.

Nestor Film Company, the first movie studio in Hollywood, was opened in 1911 by the Horsley Brothers less than a mile from the library. Actors researching their roles were frequent patrons. The film industry grew, and as a result, the population increased. Soon more businesses opened along Hollywood Boulevard. The 1913 annual report noted that much reference work was done for "scenario writers from twenty-two movie studios." It was during the mid-1910s that young women hoping to break into the movie industry began meeting in the library’s basement during the evening to read plays together. Mrs. Jones, worried about their living conditions, got the YWCA involved, which eventually led to the creation of the Hollywood Studio Club. The Studio Club (1916-1975), women-only housing with a chaperone, was home to many celebrities over the years, including Marilyn Monroe and Kim Novak.

Even though reference requests were increasing, the number of items being checked out were not "satisfactory" according to branch history reports. Circulation numbers were down. Eleanor Brodie Jones was not discouraged and instead made an effort to showcase the library as a civic and social center. Small collections of books were loaned to the Woman's Club of Hollywood, the Hollywood Hotel, and local schools (these were known as deposit stations). The Normal School and the University of Southern California helped out with storytime, lectures on music (accompanied by Victrola records) were given, and artists were invited to exhibit their work at the library. Additionally, the City Beautification Committee created a garden of native plants, which was an added bonus.

By October 1919, Hollywood had the highest circulation of any branch of the Los Angeles Public Library. Storytimes, especially during the summer, were visited by upwards of two hundred children. Lectures were being given by "Hollywood people." For example, popular programs in 1920 included lectures by William Butler Yeats and Frayne Williams. The branch, with a staff of seven, was constantly abuzz with activity, frequented by "readers of leisure," high school students, and scenario writers (aka screenwriters).

Soon the high, and consistently increasing circulation and popularity of the library meant a change was on the horizon. By the end of 1921, the library had outgrown its Andrew Carnegie-funded building at the northwest corner of Hollywood Boulevard and Ivar Avenue. The growth of Hollywood combined with the popularity of the library necessitated that a second Hollywood library, to be known as the West Hollywood Branch, was created. The Carnegie library building was dismantled and relocated, thanks to the Kress Moving Company, to the corner of Gardner and DeLongpre, where it remained until it was demolished to make way for a new West Hollywood Branch library in 1959. [The mid-century modern building that replaced it still stands at 1403 N. Gardner, although the library, now called the Will and Ariel Durant Branch, moved into a new building at 7140 Sunset Boulevard in 2005.]

Hollywood Branch Library at 6357 Hollywood Boulevard (1923-1939)

Following the move of the original Carnegie Library to West Hollywood in June 1922, work began on the new Hollywood Branch Library. For the next year, while the new building was under construction, the library was headquartered on the top floor of the Security Bank building on Hollywood Boulevard at Cahuenga. Even in these smaller quarters, which were reached by elevator, the library maintained high circulation numbers. Architects William J. Dodd and William Richards, who also designed the Carnegie-funded Boyle Heights Branch Library (later renamed after Benjamin Franklin), were chosen for the new Hollywood Branch Library.

The Los Angeles Times called the design Spanish colonial architecture with an interior of "warm buff stucco finish." The library's main entrance was on Hollywood Boulevard, and a tower held stairs leading to the second floor. The library officially opened to the public on June 26, 1923, at 6357 Hollywood Boulevard. Patrons complimented the new library on its decorative beamed ceiling, patio garden, as well as the upstairs auditorium (with seating for 200), and art gallery. Enthusiastic neighbors looked forward to "exhibits, open-air readings, and civic gatherings." Librarian Mrs. Eleanor Brodie Jones personally solicited donations to fund the oil-based murals (by unnamed Hollywood Art Association artists) in the library, instead of choosing to use watercolor. The new building also offered children their own entrance off of Ivar that led directly into the children's room. This room functioned as its own separate library and necessitated dedicated staff. It also had a fireplace. [A fireplace may seem like an odd addition in a building full of books, but many Los Angeles Public Library branches have fireplaces, including Cahuenga, North Hollywood, Wilshire, Felipe de Neve, and Angeles Mesa.]

An auditorium and an art gallery were located on the second floor of the library. The auditorium hosted meetings of many local organizations including the Hollywood Art Association, the Opera Reading Club, and League of American Pen Women. Singer-songwriter Carrie Jacobs-Bond arranged musical entertainment in the auditorium. The community art gallery, which was designed by R.M. Schindler and decorated by Donald Donaldson, regularly held shows by local artists, including Francis William Vreeland, Helena Dunlap, Edward Vysekal, E. Roscoe Shrader and photographer Viroque Baker. Interior decorator C.A. Tierney handled the interior decoration of the rest of the branch. The basement was busy as well. The Western Rangers, a boy's organization that began in the basement of the first Hollywood library, built furniture out of boxes and decorated the walls of the new library, and continued to meet there weekly.

The community showered the library with donations. The Hollywood Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution donated a flag and flagpole. They also dedicated a patio garden, accessed through the main reading room. The patio featured a fountain, designed by library architect William Dodd, of Mexican Talaveras tile and dubbed "The Lady of Silence," which was installed in 1924. The garden, which took three years of fundraising to complete, featured rare and unusual plants under the care of landscape architect Paul J. Howard of California Flowerland. The patio garden was the scene of many outdoor dramatic readings and musical performances (including Swiss folk songs sung by Dione Neutra). Librarian Eleanor Brodie Jones promoted the garden as a perfect spot for children’s storytime as well. Storytimes at the Hollywood Branch were very popular and featured a wide variety of performers who donated their time including Princess Lazarovitch of Serbia (aka actress Eleanor Calhoun) who read Serbian folk tales to the children. Screenwriter Beulah Marie Dix, perhaps best known for her collaborations with William and Cecil B. DeMille, also participated in storytime at the library by sharing stories of her New England childhood.

After only sixteen years, the library outgrew its space. Despite the Depression, the need for larger quarters for the system's largest branch was evident. The 1939 Annual Report of the Board of Library Commissioners noted that a "self-sustaining plan had to be devised." That plan involved selling the library's land on Hollywood Boulevard and relocating the library further south on Ivar Street. Back in 1906, the library was given its spot on the boulevard by Mrs. Daeida Wilcox Beveridge, and her family retained the right to buy it back. Therefore, her son-in-law, Mr. Clair Brunson, paid $230,000 (adjusting for inflation would be over $4 million today). The library's new location on Ivar cost $107,000, which left money to move and enlarge the current building in the new location. Just like its predecessor, this Hollywood Branch Library was dismantled and moved through the streets of Hollywood to its new location at 1623 Ivar. In the interim, the Hollywood Branch Library moved temporarily to 6028 Hollywood Blvd.

Hollywood Branch Library at 1623 Ivar Avenue (1940-1982)

Father and son architects John and Donald Parkinson were chosen to design the new library. Over the years, the Parkinsons collaborated to build Union Station, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum and Bullock's Wilshire. This time, the bones of Dodd & Richards' Mediterranean library were transformed by the Parkinsons into a modern and functional space. Library publicity spoke of paint harmony and indirect lighting, and "the severe simplicity of the Ivar Street elevation is accentuated by the concentration of detail at the main entrance." Patrons of the new Hollywood Library were greeted at the entrance by the Talavera tile that was part of the patio fountain at the old library. The "old" art gallery became the "new" Story Hour Room. The library opened to the public on April 29, 1940, with great fanfare– Otto K. Olesen supplied a spotlight, Mayor Fletcher Bowron was on hand to symbolically receive the keys to the building, and the first patron to use the reference department was photographed for the Los Angeles Evening Citizen News.

![Interior photo of the Hollywood Branch Library at 1623 Ivar Avenue from library history scrapbook [n.d.]. Frances Howard Goldwyn Hollywood Regional Branch Library Special Collections](/sites/default/files/media/images/blog-lapl/2022/Dig_branches/IMG_2659.jpg)

The new location continued to have many visitors, answer numerous reference questions, host local organizations and book groups in their auditorium, and invite school children to partake in their Children’s Room. The branch itself motored along with periodic painting, new directional signage, remodeling of the circulation desk, and weeding as necessary. New technologies included photographic lending (photo-lending involved a machine that would photograph a book, the borrower’s card, and the date due). Librarians noted an uptick in telephone reference questions, which they chalked up to higher transit fares that prevented some patrons from visiting as frequently. They also noted more of their patrons lived in the San Fernando Valley but still continued to use the Hollywood Library because they worked or shopped nearby. The branch was so busy that new librarians and library clerks were sent to train at the Hollywood Branch. If they could handle Hollywood they could handle anything/anywhere else. The library itself was a character. Although a branch summary makes no mention of the fact, the 1946 film The Big Sleep features a scene in which Humphrey Bogart conducts research at the Hollywood Public Library. Although likely a film set, perhaps the exposure led to more usage of the library. (The library was also mentioned in Raymond Chandler’s book of the same name as well as his novel, The Long Goodbye.)

The Hollywood Branch received much attention during Library Week 1959 (which took place from April 12-18 that year). Special window displays featuring library posters and streamers were displayed at the Security Bank, both the Pickwick and Satyr bookstores, the Broadway Hollywood book department, and the Hollywood Citizen Stationers. There was also an article titled, "Unusual Library Serves Film Folk: Unobtrusive Building Scene of Strange Requests and Women in Bathing Suits," in the New York Times that extolled the virtues of the Hollywood Branch and wondered, with all the help the library has provided the entertainment industry, how come the entertainment industry hasn’t “photograph[ed] some starlets on its steps or have cowboys fire a twenty-one gun salute” to the library. Shortly thereafter (according to a branch summary report) American Weekly, a newspaper supplement similar to Parade, photographed various celebrities (including actor Dick Powell, costume designer Edith Head, movie producer Ross Hunter and actress June Lockhart) using the library’s tools and resources. While a search for that American Weekly article has been fruitless so far, a series of photos on Tessa that provide a snapshot of the library’s patrons at the time is informative and entertaining (1950s graffiti!).

![A young Hollywood Branch Library patron looking at the latest non-fiction books [1959]](/sites/default/files/media/images/blog-lapl/2022/Dig_branches/photos_98496_medium.jpg)

According to library reports and newspaper accounts, the Hollywood Branch Library was plugging along as a library does–until the morning of April 13, 1982. Unknown persons broke in through windows in the back of the library and proceeded to have a party before starting a fire behind the circulation desk. It was estimated that the library burned for at least an hour before anyone noticed. According to the Firemen’s Grapevine, it took fifteen companies of firefighters one hour and twenty-two minutes to put out the blaze. The library was destroyed, more than two-thirds of its books burned, and one-of-a-kind special collections up in smoke, including the library’s entire Theatre Arts Collection.

The community rallied around the library immediately and began working on a plan to rebuild. The Los Angeles Times ticked off some of the one-of-a-kind or rare items that burned, including notebooks of D.W. Griffith and Charlie Chaplin, silent movie picture scripts, and old theater programs. The damage totaled $3.5 million. Jack Smith lamented the loss of the library in his Los Angeles Times column, describing a visit to the charred remains. Johnny Carson set off the donations by pledging $10,000. People donated money and books. Club Lingerie held several "Save the Library" fundraisers. Hollywood Heritage gave walking tours through historic Hollywood to benefit the library. Ultimately, the Samuel Goldwyn Foundation donated $3.24 million and hired Frank Gehry to rebuild the library. As a child, Samuel Goldwyn Jr. and his mother, Frances Howard Goldwyn, visited the Hollywood Branch Library in its previous location on Hollywood Boulevard at Ivar. Ms. Howard (1903-1976) was an actress and model before marrying producer Samuel Goldwyn Sr. in 1925. She left acting and began collaborating with Goldwyn’s productions, taking over the supervision of Samuel Goldwyn Productions in 1969. Frances Howard Goldwyn (1903-1976) was an avid reader and library user, and the new library was named in her honor.

Hollywood Branch Library at 1623 Ivar Avenue (1986-Present)

Four years after the arson, the Frances Howard Goldwyn Hollywood Regional Library opened in June 1986. [Sadly, the Central Library had also been a victim of arson less than two months earlier]. This was Frank Gehry’s first original library design, and there had been criticism when the design model was presented to the public in 1983. In the end, the design was completely unique, with reflecting pools and a five-story window facing Ivar, truly unlike any other branch of the Los Angeles Public Library. In the book The Architecture of Frank Gehry, Mr. Gehry described his intentions for the Frances Howard Goldwyn Hollywood Regional Branch Library. Check it out to learn what he had to say.

The Hollywood Public Library continues to be a beloved asset to its community. From its earliest years, the library provided a space for artists to show their work in Los Angeles’ burgeoning art scene. In the 1920s, Hollywood librarian Eleanor Brodie Jones instigated the Hollywood Studio Club to help the young women who came to Hollywood to break into the movies. Movie studios used the library for research and even lured some of the librarians to help the studios build their own research departments. Will and Ariel Durant famously utilized the Hollywood Public Library’s resources when writing The Story of Civilization series (the library reciprocated their love by naming their West Hollywood Branch after the couple in 1988). Authors such as Raymond Chandler and James Ellroy made the library a character in their books. And celebrities such as Paul Newman, Joanne Woodward, Johnny Carson, and Orson Welles used this branch and/or came to its defense following the devastating 1982 fire that destroyed the library. Thanks to the generosity of the film industry and the Hollywood community, new Special Collections, including books, production files, unpublished scripts, playbills, movie posters, and local history materials such as Holly Leaves, an early Hollywood newspaper, can be visited whenever the library is open. Visit the library and see the history that is still being made today.