This post is the seventh in a series of excerpts serializing the book Feels Like Home.

Chapter 2

From Belle to Burden and Back Again - part 3 by James Sherman, Librarian, Literature & Fiction Department

We continue the story where we left off in 1980, with the success of a lawsuit filed by the Southern California chapter of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) to stay operation of the Central Library expansion and renovation, which demonstrated the growing power and organization of the preservation movement, not just for Central Library, but for Downtown Los Angeles.

After the lawsuit, the AIA’s Southern California chapter produced detailed guidelines for preserving the integrity of Central Library. This document was edited by Margaret Bach, who was later to become the head of the Los Angeles Conservancy, which played an important role in stopping the next attempt to destroy Central Library.

That attempt occurred in 1981 when a plan emerged that would trade development rights on the current library site to a private developer in exchange for a new central library facility at effectively no cost to the taxpayers. The Library Board called again for proposals for a new library, and the preservationists realized again, as with so many past proposals, that these plans involved the sale of the library property for the cash strapped city, which would likely mean the demolition of the Central Library.

One of the main plans discussed was two fifty-story towers on the space in return for a new central library gratis to the taxpayers: according to Joseph Giovannini in the Herald-Examiner, “the RFP disclaims any responsibility for the loss of the old library by mentioning the theoretical possibility of retaining the old structure” with no other mention that the building should be saved. Giovannini further noted that library staff had drafted the RFP without consulting the L.A. Conservancy or the Los Angeles Chapter of the AIA: “...the case might be made that the librarians monopolized the initiative despite the documented interest of other parties.” While the staff and patrons were the “identifiable users,” there were “other legitimate custodians who were excluded from the RFP” such as the AIA and the Conservancy. Furthermore, the president of the City’s Cultural Heritage Board, Dr. Robert Winter, noted that “the first time the board saw the document was in January when ‘it was already a fait accompli’”.

In an ominous foreshadowing, Giovannani also noted in a Herald-Examiner column of April,1981—five years before the fire—that the library was under citation for fire code violations, which required a correction plan by the end of the month, “by default the RFP seems to be the only promise of keeping the library open... even though there is, according to the fire department, no panic situation” and quoted Public Safety Second of the LAFD Ronnie Wreesman that in fact, the library presents “no great fire hazard”, a “2 or a 3 on a scale of 1 to 10”.

In response, the newly formed Conservancy cut its teeth by initiating a successful telephone campaign to reach Mayor Tom Bradley and Councilmember Gilbert Lindsay, the latter of whom had once called the library “disgraceful” and referred to it as a “heap of junk,” but who now supported saving the Central Library. Times were definitely changing.

Along with attorney John H. Welborne, The Los Angeles Conservancy was instrumental in forming Citizens’ Task Force for Central Library Development “to seek a viable solution that addressed the functional needs of the library and the cultural significance of the historic building.” The Task Force included representatives from the CRA, downtown corporations such as ARCO, developers, architects, and city officials, including City Librarian Wyman Jones, who was asked to join the steering committee. The Task Force was successful in convincing Mayor Tom Bradley to delay the RFP process and instead to accept an offer of an outside consultant who ended up recommending the renovation and expansion of Central Library. But how? Who would have the ways and means for the project that had bedeviled city politics for so long?

Enter developer Robert F. Maguire III. Maguire was a regular lunch partner of ARCO’s Robert O. Anderson, who would “often gaze down from his 51st story office and grouse about his shabby neighbor across the street”. Together they funded a plan to save the library, a plan that would win the hearts of the aesthetes, address the concerns of the politicos and leave untouched the taxpayers’ purses.

Maguire was a combination of savvy and taste that had been missing in the first explosive growth of the sixties, during which developers were about the Deal, not the building, and fostered an unfortunate “take the money and run” attitude. Maguire was a different sort of developer, in that he brought a sense of aesthetics to his business practices, and with suggestions of IM Pei and Philip Johnson as his architects, he not only won over AIA but also, as he himself later suggested, “...maybe I called upon the clout of East Coast Biggies to impress the local money men and politicos”. Like Luckman, Maguire didn't quail from political fray, with serious political donations and long-term personal connections, such as one partner who worked on Tom Bradley’s gubernatorial campaigns. Unlike Luckman, Maguire was very good at building consensus and open process, to avoid the skullduggery of backroom dealing.

Even with these advantages, in 1980 Maguire lost a billion-dollar contract for Grand Avenue projects along Bunker Hill and so was looking for another high-profile project to take advantage of downtown’s growth. It was natural that the Library project became his focus. Maguire came up with the wherewithal in the form of a package worth $125 million to fund a sensitive renovation and expansion to the Central Library, in exchange for Air Rights that would support a massive development project on neighboring properties, which would include a building far taller than would normally be allowed.

While pitching his plan to civic and business leaders, Maguire was quietly and quickly buying up properties neighboring the library, including the Engstrom apartments property on the north side of Fifth Street. In doing so, he outbid and therefore annoyed a development company that was part of Rockefeller real estate investments, which owned an adjacent property crucial for the project. Maguire ended up with that too, putting himself far ahead of any competition for development of the library project. In the words of another developer, “Maguire was the only one that close to the site.” His attention to aesthetics, commitment to open process and shrewd business acumen resulted in Library Square.

Maguire’s Library Square project built the monumental Library Tower (also known as the U.S. Bank Tower), the Gas Company Tower, and added the Bunker Hills Steps. For the Library property, Maguire constructed an underground parking garage and helped transform the eyesore of the street level parking back to the beauty of the West Lawn garden, helping to make open space into green space again.

Maguire had managed to cut through the Gordian knot of the complicated project and worked well with the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA), which had been entangled for years over frustrated plans regarding Central Library. As CRA’s Edward Helfeld asserted, “Without Maguire...we couldn’t have done it.” He chose the ways, then the means: Maguire and CRA chose architectural firm Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer to come up with a design that would truly preserve the historic structure. In 1985 the City Council, backed by the Los Angeles Conservancy, approved the project, and it seemed that fortunes had finally turned in favor of the Central Library.

Then, disaster struck.

James Sherman is a reference librarian in the Literature & Fiction Department at Central Library. He has worked as a young adult librarian, a community college reference & instructional librarian, and a cataloger & electronic resources librarian at a law firm. He has an M.F.A from UCLA's School of Theater, Film and Television and has worked for the Sundance Institute as well as in development and physical production. James also worked as a grant writer for arts organizations and as a consultant researcher for the NYC Board of Education and the United Nations Development Programme.

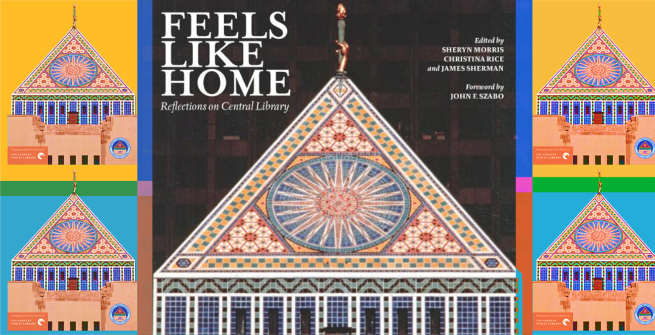

Feels Like Home: Reflections on Central Library: Photographs From the Collection of Los Angeles Public Library (2018) is a tribute to Central Library and follows the history from its origins as a mere idea to its phoenix-like reopening in 1993. Published by Photo Friends of the Los Angeles Public Library, it features both researched historical accounts and first-person remembrances. The book was edited by Christina Rice, Senior Librarian of the LAPL Photo Collection, and Literature Librarians Sheryn Morris and James Sherman.The book can be purchased through the Library Foundation of Los Angeles Bookstore.