This post is the sixteenth in a series of excerpts serializing the book Feels Like Home.

Chapter 7

Los Angeles Central Library Project – The Short Version - part 2 by Betty Gay Teoman, Central Library Director 1984-1998

Three years of public meetings and newspaper articles about this huge public project had not captured the general public’s attention. The fire, however, created a groundswell of Los Angeles community support.

That first volunteer crew included 1700 people of all ages who came downtown from all over the County to staff recovery teams which worked 24-hours-a-day. The CAO immediately found us the salvage company, Document Reprocessors, and City Council urgently approved the required funds. Community volunteers removed books from the wet, dark building and packed them for freezer storage. By Saturday morning, the last pallets of wet books were lined up along Hope Street waiting to be picked up for delivery to freezer storage in a produce district warehouse.

And planning for the Central Library project became even more complicated. It also became very personal for everyone who had worked in the damaged building, all of whom were immediately given new assignments, mostly in new locations. Administration and technical services had to be immediately reactivated to support the system. Locating and planning temporary Central Library facilities then became the system’s highest priorities. Day-to-day staffing and book recovery efforts had to be managed. On September 3, 1986, a second arson fire in the art & music wing caused further damage to the collections and to everyone’s emotions and morale.

It wasn’t initially planned that way, but because continuity was important, I had become the library’s project manager and, after February 1984, also its Central Library director. It was only possible because staff in the Central Library director’s office and the subject department managers carried a very heavy workload. They were bright, hard-working, able to work very independently, and knew when to communicate and when to ask for help. I was responsible for Central Library’s operations, but they managed them.

After the fire, we had a lot of new tasks. The 395,000 burned books were gone, but which ones? The 750,000 wet books were frozen and staff questioned whether they would ever return. Books remaining in the library needed to be inventoried to begin a new catalog. The old card catalog sat in the rotunda, untouched by the fire, but an artifact. We had to find and outfit a temporary Central Library, but before we could open it, we had to plan and activate a book processing center to complete the recovery of the salvaged frozen books. The work was hugely complex, and Joan Bartel, Pat Kiefer, Lori Aron, and Ruby Turner, in particular, were amazing. Every one of the subject department managers should be added to that list along with managers and staff from technical services and administrative offices. The post-fire period demanded great resourcefulness from everyone.

Budget - During the lengthy planning period, the project budget predictably increased substantially. The financing plan was very complex, with a substantial amount coming from the sale of Air Rights and Tax Increment Bonds issued by the CRA. CRA proposed a sale-leaseback of the historic building as the third funding source. It added many legal and planning steps to the process. The City’s planning team would hold its collective breath at the end of each architectural design stage when HHPA presented an updated construction cost estimate.

In November 1987, the city council approved a $152.4 million Central Library project budget. By April 1993, it approved the final $213.9 million budget. Each time costs increased, the planning team and CAO thoroughly documented the dollars required. And the city council approved the funds and reinforced its support for the library. This budget does not include the cost of fire recovery efforts and temporary quarters for library departments. The city’s commitment was huge.

Early in the budget process, the city proposed to delete the auditorium from the project as a cost savings. We struggled mightily with that key issue and found an advocate in councilman Joel Wachs. He introduced a motion on the council floor to add the auditorium back to the budget, stating he was confident a donor would be found in the future to pay for it. It was critical to the project, and he was right—the Mark Taper Foundation donated $1 million to name the auditorium.

Art Projects - The CRA intended the Central Library design to faithfully follow the secretary of the interior’s standards for rehabilitation. It saw the substantial cost of rehabilitation of the Goodhue building as the Central Library project’s contribution to art. Then, in 1988, the Cultural Affairs Commission required a percentage of the project budget be dedicated to new art projects. Architect Norman Pfeiffer proposed that functional elements of the building’s new wing be designed and produced by artists: elevators, Atrium chandeliers and standing light fixtures, children’s courtyard fencing, and fountain. On the west lawn, fountains became additional art projects. The selection of artists began in December 1988. The art projects require their own article—it’s a great story.

Last Thoughts - My title promises “the short version” and this actually is. Among the issues it doesn’t address are the support we received from the Getty Conservation Institute, the Save the Books Campaign and ARCO fundraising staff, and the huge complications of moving the library into Spring Street and then back home to West Fifth Street.

The May 22, 1989, opening of the Spring Street Central Library was a landmark day. The city had been without a Central Library for nearly three years. That time was hard on the community and particularly hard on us. We kept thinking we should make it happen sooner—for the public and for the staff.

More than 3700 people attended the day-long Open House on the Saturday before the official opening. Seeing people, especially families, using the library again was a huge milestone for everybody and a great pleasure.

The October 3, 1993, Fifth Street reopening was most memorable for the huge enthusiastic public in attendance—who didn’t appear to care on that day that signs were missing throughout most of the building. It took many months after opening day to complete work on what was a bit more than a punch list. And of course, few things worked quite like they were supposed to, but we learned quickly.

Working with the HHPA team led by Norman Pfeiffer and Steve Johnson for nearly ten years was a great pleasure and steep learning curve. No matter what happened in the lengthy review, planning, and construction process, they never got excited. They just went to work to find a way to resolve any issue that was raised. My job was focused on function—to make sure the building HHPA designed worked well as a library. I channeled to them the plans, decisions, and best thinking of all of us in the library. Then library staff and I checked the work each time HHPA revised the plans to make sure they included everything we asked for—and that what we asked for worked well on the plans.

After one of the early public design reviews, I left the meeting deflated by the harsh reception for the Central Library’s latest design. Norman told me, “Don’t worry, we’ll change it and make it look great.” Design was his responsibility and he and HHPA were very good at it. Our roles were clear, and I didn’t worry about design again.

It gives me pleasure to see HHPA’s subtle design signatures in the building: former history room ceiling and rotunda mural motifs subtly repeated in the new children’s room carpet; Goodhue building ceiling patterns in the east wing carpets; and the Central Library building woven into the Mark Taper Auditorium’s upholstered seats. They were respectful of Goodhue’s work and carried its themes throughout the building in a thoughtful, clever, and sometimes whimsical fashion.

The CRA proposed a Central Library project which was a public-private partnership. Both sectors rose to the occasion. It showed exactly what the City of Los Angeles, its businesses, and its community can do when they do their best. Working on this project was exhausting and exhilarating. I wouldn’t give anything for having had the opportunity to be part of the enormous team which built the rehabilitated and expanded Central Library.

Betty Gay Teoman began her career at the Los Angeles Public Library in 1969 and held a variety of positions throughout the system before coming to Central Library in 1984. From 1983 until the October 3, 1993 re-opening of the rehabilitated and expanded Central Library, she also served as the Library’s Liaison and Project Manager, working with Hardy Holzman Pfeiffer Architects and City and Community Redevelopment Agency staff to complete the building’s planning, design, financing, and construction. It was a creative, successful public-private partnership. Due to the 1986 arson fires which struck the building, this work included assisting with disaster recovery efforts. In 1998, she retired from the Los Angeles Public Library after a 30-year career, later lending her expertise to the Rye Free Reading Room in Rye New York and the Rancho Mirage Public Library. Currently retired, she resides with her husband Kory in Rancho Mirage.

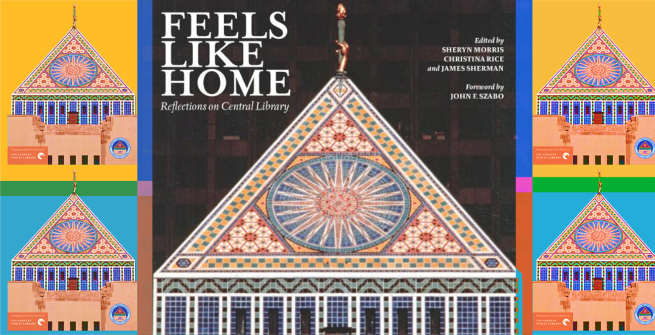

Feels Like Home: Reflections on Central Library: Photographs From the Collection of Los Angeles Public Library (2018) is a tribute to Central Library and follows the history from its origins as a mere idea to its phoenix-like reopening in 1993. Published by Photo Friends of the Los Angeles Public Library, it features both researched historical accounts and first-person remembrances. The book was edited by Christina Rice, Senior Librarian of the LAPL Photo Collection, and Literature Librarians Sheryn Morris and James Sherman.The book can be purchased through the Library Foundation of Los Angeles Bookstore.