This post is the fourth in a series of excerpts serializing the book Feels Like Home.

Chapter 1

"A Wanderer and Homeless Waif": Los Angeles’ Central Library - part 4 by Glenna Dunning, Former Librarian, History & Genealogy Department

The library clearly needed to move in a new and bold direction; the Board itself moved in a new direction when it hired Everett R. Perry to replace Charles Lummis, who had resigned in 1910. Perry arrived in Los Angeles with ambitious plans for the rapid development of the central library and extension of service through the branches and deposit stations but, during his first visit to the library, "he was shocked to hear the elevator operators call out the library floors between the women's wear and the furniture, and, coming from New York, seems to have considered this as something of an excess of Western informality.” It was clear to Perry that there were several challenges to be met and one of the most important was the ongoing, seemingly never-ending, space problem. Perry realized that, due to the Hamburger Building's structure and layout, an extension or rearrangement would be impracticable; a move was imperative.

The Library Board agreed with that assessment and wrote in the 1912 Annual Report that "development of the work at the central library has been greatly hampered...[because] the arrangement of departments is inconvenient for attendants and the public. Only when the collection is housed in a new building of our own, so planned as to embody the most recent ideas in library construction, can the most efficient service be rendered." It was the unanimous opinion of the Library Board and Perry that the best interests of the library could not be served by remaining in the Hamburger Building. Because the lease with Hamburger Realty had expired, they agreed to renew the lease for one additional year while beginning the search for more appropriate quarters.

Recalling the various problems encountered in the Hamburger Building, the Board conducted a thorough and exhaustive search for a suitable building. After considering various options and suggestions, negotiations were made with the owners of the new Metropolitan Building, then being constructed at Fifth and Broadway. A lease was signed for new quarters on the seventh, eighth, and ninth floors of the Metropolitan Building at a cost of $22,000 per year (which, in terms of cost per square foot, was cheaper than the Hamburger Building). The Board was convinced that "these quarters will furnish most satisfactory arrangements for the library until such a time as it is able to move into its own permanent quarters. The plan that has been worked out will give excellent elevator service and the best of facilities for all visitors to the library and, owing to the convenience of its location, it is confidently expected that the Central Library will enjoy a much larger patronage than heretofore."

The move to the Metropolitan Building was completed on May 30, 1914, an occasion that prompted an anonymous wit to observe "that the library had traded tenancy in a department store for rooms over a drug store." Nevertheless, patrons who visited the library for the first time were duly impressed and the Los Angeles Times reported that, during the first weeks of operation, a great number of readers made the same remark: "At last Los Angeles has something that looks like a real library!"

The library's annual report for 1913/1914 discussed the new quarters in the Metropolitan Building and listed some of the "many advantages both to the staff and the general public. The floor space is about 50% larger than in the old location. The library now enjoys an abundance of light and air, and a highly accessible location in the very center of the shopping district, thus assuring the greatest convenience to its many patrons. The new quarters are completely divorced from any commercial enterprise and have been most carefully planned by the Librarian and his assistant to afford every comfort to readers. Owing to the improved arrangement all the books are now placed on open shelves, something much appreciated by the public. It was pointed out that the new lease ran seven years, but it was "confidently expected that the City of Los Angeles will provide a new building by the time of its expiration."

Floor plans indicate that the seventh floor contained the periodical reading room, the children's' department, and the school and teachers' department; the eighth, or main, floor contained the circulation and reference departments; the ninth floor housed the Industrial, the sociology and the art departments and the tenth had the administrative and staff departments of the library, and the library school. There were, as well, "special mezzanine departments, for all of which a single public entrance and exit is provided.

The library operated successfully in the Metropolitan location for several years, its collection and patron base steadily increasing. By 1918, however, it was not surprising to read that the library was beginning to run out of room. The annual report for 1918/19 revealed that "the location of the main library in the Metropolitan Building is not wholly suitable, and the quarters have become much too cramped for the best presentation of library facilities to the public. The lease upon these quarters is of short duration and the time is drawing dangerously near when definite and positive action must be taken for a change...Besides being a handicap it is a stigma on the good name of Los Angeles to be obliged to rent rooms in which to house our Central Library, one of the institutions to which our citizenship should be able to point with special pride."

The Library, under Perry's leadership, began to press its efforts to educate the public on the need for a permanent home. It was a revelation to many citizens to learn that "The Los Angeles Public Library, after nearly half a century of constructive educational work and remarkable growth, [was] the only library of importance in the United States which has never had a central building of its own or has no such building in actual prospect. Perry wrote that there "must be developed a plan for a central site and new library building for the public library. The need for this has been discussed, understood, and appreciated by those who know the facts, for a number of years. We believe the time has arrived to act, and we are now preparing to go before the citizenship of Los Angeles and ask that a bond issue be voted to raise the funds necessary to acquire a new site and to build a library building suitable to the needs of the community."

The city responded to Perry's argument and, in 1921, a bond issue was passed which provided $2,500,000 for a central library building and branches. Then, in 1922, Normal Hill, the former location of the old State Normal School, was deeded to the library by the City Council. Almost immediately, the Los Angeles Times reported, the City's Welfare Commission requested from the Board of Library Directors a guarantee that "facilities for playground and recreational purposes be included in library plans for Normal Hill.” Superintendent Raitt, of the Playground Department, asked "If the request is refused what is to become of the hundred and one public interests that have been built up around this old Normal Hill Center?" But a more basic question faced the city: what to do with the old building which still stood on Normal Hill. It housed several city departments and the city was hard-pressed to find another home for these departments.

A surprising and unwelcome announcement was soon made to the Library Board: in spite of the fact that the City Council had deeded over the property at Normal Hill, it was expected that the library pay $100,000 to the City Treasury to cover the cost of demolishing the structure which was standing there. A considerable amount of hard feelings grew between the Library Board and the City Council and, at one point, councilman Mallard labeled board members as "welchers" for their failure to pay. This antagonism was threatening the future of the new central library, as were the demands of a small but vocal citizens' group which opposed library construction on Normal Hill, insisting that the site should be in Pershing Square (formerly Central Park).

But the library was too close to its dream to let the opportunity slip away, and cooler heads prevailed. On January 23, 1923, the City Treasurer received the $100,000 from the Library Board ("in the return for the gift of Normal Hill”), and the agitation for the Pershing Square site faded away due to a lack of interest. The Normal Hill site was cleared and construction of the library began, but it was not until 1926 that the dream finally became reality. The degree of public support and excitement was evident when, on June 19, 1926 "the crowd cheered when the moving van drew up to the Metropolitan Building...to cart away the preliminary loads from the Public Library quarters to the new building, the permanent home of the Los Angeles Public Library."

Glenna Dunning (1947-2015)

In the History & Genealogy Department at Central Library, Glenna Dunning was the go-to librarian with questions relating to really early Los Angeles history and was able to keep all those adobes and ranchos straight. If some aspect of Los Angeles history piqued her interest, it wasn’t long before an article she penned on the subject showed up in the Los Angeles City Historical Society Newsletter. Glenna’s many historical writings are cited in the library’s California Index and serve as a tangible reminder of the dedicated librarian who served her beloved city well. A fully cited version of “A Wanderer & Homeless Waif” is available on request.

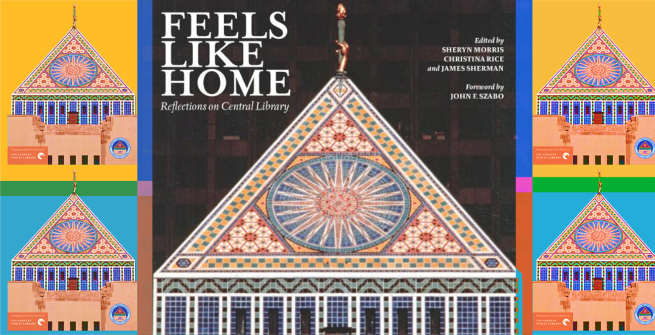

Feels Like Home: Reflections on Central Library: Photographs From the Collection of Los Angeles Public Library (2018) is a tribute to Central Library and follows the history from its origins as a mere idea to its phoenix-like reopening in 1993. Published by Photo Friends of the Los Angeles Public Library, it features both researched historical accounts and first-person remembrances. The book was edited by Christina Rice, Senior Librarian of the LAPL Photo Collection, and Literature Librarians Sheryn Morris and James Sherman.The book can be purchased through the Library Foundation of Los Angeles Bookstore.