A picture may say 1,000 words, though there is possibly another story lurking just outside the frame.

At first glance, these selections from the LAPL Photo Collection might appear to be a random assortment of images relating to crimes from Los Angeles’ past. From the oft-discussed and still unsolved deaths of Thelma Todd and Elizabeth Short to the lesser known cases of accused murderess Nellie Short, and newlywed bandits Thomas and Burmah White, the photographs all have two things in common; The Los Angeles Herald and Aggie Underwood.

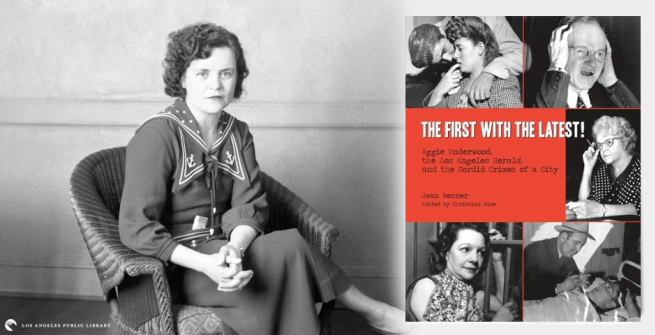

Agness “Aggie” Underwood, got into the newspaper business by accident when she took a temporary job with the Los Angeles Record in 1926 as a switchboard operator in order to buy herself a new pair of stockings. The energy of the newsroom thrilled Aggie and she became bound and determined to become a reporter. Under the tutelage of Gertrude Price, writer of the women’s column for the Record, Aggie proved to be a quick study with an amazing intuition. Within a few short years, she began making a name for herself as an ace crime reporter.

In 1935, Aggie accepted a position with the Los Angeles Evening Herald and Express, one of two local papers owned by William Randolph Hearst (the other being the Los Angeles Examiner). She quickly formed a tight bond with photographer Perry Fowler and together the pair spent the next decade documenting many of the city’s more sordid crimes while helping their newspaper live up to its motto “the first with the latest.”

In 1947, while covering the notorious Black Dahlia case, Aggie was promoted to editor of the city desk, making her the first woman of a major metropolitan newspaper to hold that position. For the next twenty-one years, Aggie cemented her reputation as a firm but fair editor who kept a baseball bat at her desk for dealing with overzealous publicists and a starter pistol in a drawer for when the newsroom got too quiet. Agness Underwood remained the city editor following the merger of the Herald and Examiner in 1962, and retired in 1968. She passed away in 1984 when she was 81 years old.

The Los Angeles Herald Examiner folded in 1989 and the Los Angeles Public Library subsequently acquired its photographic archive. Within those files, brought to life in light and shadow, are images of the cases Aggie Underwood covered as a reporter with the paper in the 1930s and 40s, and recounted in her 1949 autobiography Newspaperwoman. The selected photos not only tell a story of Los Angeles crime, but of the woman standing nearby (and sometimes in the frame) with her trusty pen and notepad poised and ready to be “the first with the latest.”

Actress Thelma Todd was found slumped over in driver’s seat of her Lincoln in December 1935. She had succumbed to carbon monoxide poisoning, though the exact circumstances still remain a mystery. Thelma’s autopsy was the first Aggie Underwood ever attended. By the time it was over, all of Aggie’s colleagues had turned green and fled the room—only she and the coroner’s staff remained upright. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Burmah White (standing) was a hairdresser in Santa Ana before she married Thomas and embarked on a short but bloody life of crime. The 19-year-old is smiling in the photo but during her trial, she was surly and unrepentant. Aggie Underwood interviewed Burmah two years later at Tehachapi prison and her attitude had completely changed. She even wrote an open letter to young women entitled “Crime Never Pays.” (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Nellie Madison testifies during her trial for the murder of her husband, Eric. She was convicted and sentenced to hang. She would have been the first woman executed in California, but Aggie Underwood wrote articles in defense of Nellie who had suffered severe physical abuse at the hands of her husband. Aggie’s articles and public outcry convinced the governor to commute Nellie’s sentence to life in prison. Aggie traveled to Tehachapi to deliver the news. Overcome with emotion, Nellie embraced her and wept. She said, “You did it! You did it! I owe it all to you!” (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Clara Phillips (center) served 12 years in prison for the 1922 brutal hammer slaying of Alberta Meadows, and had been extradited from Honduras for the trial. Aggie Underwood (right foreground) journeyed to the California Institution for Women, Tehachapi for the killer’s release on June 17, 1935. Her piece on Clara’s return to the world made the front page. Clara left prison with a fanfare, but then slipped quietly into obscurity as a dental assistant in San Diego. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Hazel Glab poses next to the bars in her cell at the Hall of Justice Jail. She was facing trial for the murder of her husband eight years earlier. Prior to her arrest, Hazel had granted Aggie Underwood an exclusive interview. To keep the other newshounds from stealing her thunder, Aggie took Hazel home with her. They arrived to find 40 little girls from Aggie’s daughter’s Girl Scout troop enjoying a potluck dinner. Hazel pitched in and helped serve and then clean up. Unfortunately, there is no merit badge for dining with a murderess. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Leroy Drake cooling his heels in a cell after being charged with the poison murders of his aunt and uncle. This photo was taken by Aggie Underwood’s colleague and friend, Perry Fowler. Perry couldn’t believe his ears when he heard Aggie say to Leroy, “…you poor thing. Now suppose you tell me all about it.” It was part of her technique to get the suspect talking, and it worked perfectly. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Samuel Whittaker (left) was a retired church organist and a man with a plan. He hired drifter James Culver (right) to fake a holdup. Ostensibly Whittaker wanted to teach his wife not to be careless with her jewelry. Whittaker’s actual plan was to kill both his wife and Culver, and then blame the dead robber for everything. Whittaker was caught out by Aggie Underwood when she saw him wink conspiratorially at Culver during this photo shoot. She told LAPD detective Thad Brown what she’d seen and Whittaker was subsequently busted. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Laurel Crawford points down the slope of 1000 foot cliff over which his automobile plunged killing his entire family. Crawford claimed that he had leaped from the car at the last moment and was spared. When Aggie Underwood arrived she had a hunch that Crawford’s display of grief was phony. Sheriff’s investigator Lieutenant Garner Brown asked her for her opinion. Without hesitation, she said, “I think it smells. He’s guilty as hell.” She was right. and Crawford was later convicted of murdering his family for insurance money. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Louise Peete (left) interviewed by Aggie Underwood (right) for the last time. Louise was sentenced to death in the gas chamber for murder. When the death sentence was handed down Louise turned to Aggie, pinched her under the chin, and said, “Now don’t you cry.” Three years later, Aggie was present for the execution where Peete passed around a box of chocolates to the gathered reporters just before entering the gas chamber. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Arthur Eggers raised his right hand and swore to Aggie Underwood that he could not possibly have murdered his wife, Dorothy, or cut off her head and hands because, “As God is my judge, we had rabbits once and I couldn’t even butcher them.” He was ultimately executed for the crime. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Robert Manley’s portrait looks like a still from a film noir. He was the first suspect in the slaying of Elizabeth Short, aka the Black Dahlia. Aggie Underwood interviewed Manley and concluded that he was innocent—the cops agreed and released him. The infamous unsolved murder was the last case that Aggie covered as a reporter. A few weeks into the case she was promoted to city editor of the Herald. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Aggie at her desk in 1949, two years after becoming the city editor for the Los Angeles Herald and Express. Visible is the baseball bat she kept handy in case she needed to keep overzealous Hollywood press agents in line. Not seen is the starter pistol she also kept on hand in case the newsroom became too quiet. Aggie remained city editor until she retired in 1968. (Los Angeles Herald Examiner Collection)

Further Reading

The First With the Latest!: Aggie Underwood, the Los Angeles Herald, and the Sordid Crimes of a City