This blog post series looks at the history of the 1905 firing of Mary L. Jones as Los Angeles City Librarian. It reveals the sexism that influenced the library’s Board of Directors and shaped their decision to actively place a man, Charles Fletcher Lummis, at the head of the Los Angeles Public Library; their decision would set off a firestorm across the city.

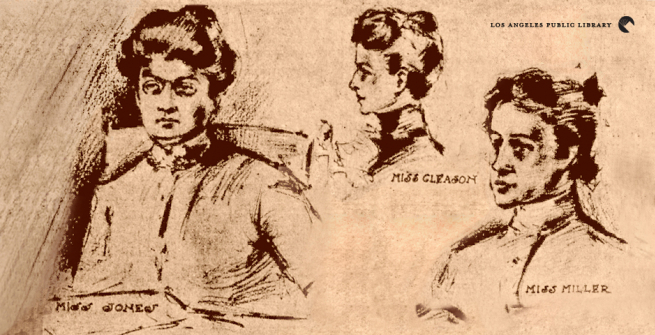

On June 16, 1901, The Los Angeles Herald announced that the Library Board of Directors had created a Second Assistant Librarian position and had appointed Miss Nora Miller to this position. Miller had been working at Los Angeles Public Library since the mid-1890s and had been head of the Registration Department under City Librarian Wadleigh. The position of Second Assistant Librarian had existed under Wadleigh but had been abolished by the board upon her retirement. The Herald explained that Member Dockweiler had been behind creating the position and urged his fellow board members to support the motion at the board meeting that took place May 29th. Only one board member, Lee Philips, voted against the measure. The new position meant that, in the absence of both Jones and the Assistant Librarian, Celia Gleason, Miller would be in charge of the library. The addition of the second post also meant that Jones now had to consult with Miller regarding administrative matters pertaining to the library. The Herald explained that neither Jones nor Gleason were consulted on Miller’s appointment, nor were they made aware of it until after the fact.

The Herald connected Miller’s appointment to nepotism: “Miss Miller’s relatives and friends are known to be political friends of Mayor [Meredith P.] Snyder and the latter is said to have aided her advancement.” The Los Angeles Times reiterated this point but placed the blame on the shoulders of Member Dockweiler. A June 30, 1901 column in the Los Angeles Times attempted to defend Miller’s appointment based on merit, stating that she had scored higher on her civil service examination than her colleagues, however it did not address why a position that had been eliminated was suddenly active again nor did it address why Jones was not consulted on administrative matters taking place within her department. The board made the following statement in the 1901 Annual Report for the library (published in December of that year):

“Recognizing the necessity of doing so, this board filled the position of Second Assistant Librarian, then vacant, by the appointment of Miss Nora Miller...in promoting her to this position we strictly observed the civil service rules of the library that have been in force for the past ten years and more.”

Jones’ report for that year acknowledged Miller’s appointment but the report remained professional and any acrimony was not addressed. Jones closed by thanking the Board for their support. The only negative statement ever attributed (publicly) to Jones regarding the new library assistant was a word play on a line taken from Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essay on Friendship; Jones stated that Miller represented “the slush of concession” (Emerson’s original phrase was the ‘mush of concession’), a statement that became notorious throughout the Los Angeles press and became a point of contention during the investigation of charges against her. Jones never explained what the phrase was intended to mean and would, later, say that she unintentionally misquoted Emerson; the damage, however, was done.

There can be little doubt that Miller’s appointment caused tension within the library and in 1903 Miller filed charges with the board against Jones alleging inefficiency, mismanagement, unfair treatment to the training class and “conduct unbecoming a lady.” Miller had alleged that Celia Gleason had exerted an undue amount of influence over Jones and had been taking over many of the administrative functions that should have been assigned to Jones. She also alleged that she was given a disproportionate workload (compared to Gleason) and Jones had failed to consult with her in matters pertaining to the administration of the library. She also charged that Jones had been unnecessarily cruel to the women in the training class (a small group of women was being trained as library clerks by the senior librarians). The pending investigation was splashed across Los Angeles newspapers and became a hot item throughout the press in the growing city. The Los Angeles Times stated what seemed to be the popular sentiment at the time:

“It is said that Miss Miller has been acting as a spy on Miss Jones; that the desk of the second assistant was placed in the office of the librarian in order that the espionage might be conducted to better advantage, and that various little devices have been adopted to irritate Miss Jones and to make her tenure of office as uncomfortable as possible.”

The Los Angeles Herald was more to the point: “this is a well-digested plot to railroad Miss Jones out of her position, and that to cover the plotters tracks ‘public scandal’ will be avoided by private intrigue.” The training class submitted a letter to the Board in support of Jones, rebuffing Miller’s accusation:

"Having read in the papers that Miss Mary L. Jones, librarian, has been accused of unfairness and unjust treatment of the training class, we, the undersigned members of the class, wish to state that Miss Jones has always treated us justly and with fairness, and and that we have no complaint whatsoever.”

Among the signatories was Kathleen Miller, the sister of Nora Miller.

Nora Miller had run afoul of the City Librarian previously. In January 1899 she had been suspended pending an investigation that she had been holding books for her friends. In 1906 Jones testified that she reported anomalies with Miller’s business transactions to the board but nothing ever came of it. In March 1907, the Herald reported that ‘auditing power’ had been taken away from Miller following the City Attorney’s report that a bill for books had been submitted and paid, twice. Following that incident, an accountant was hired to audit all transactions; Miller was reported to have resigned from Los Angeles Public Library shortly thereafter, although it was stated that she left to be married.

The board attempted to investigate the charges against Jones out of the public eye but Jones insisted that the case be made public. The board members didn’t discuss the matter with any depth within the press, dismissing it simply as “a woman’s spat.” Library Board President J.W. Trueworthy did make comments to the Times where he compared the situation to an altercation among “children” who had to “take their troubles to their parents” in order to resolve them. In the end, the Attendant’s Committee that reviewed the matter recommended that the charges against Jones be dismissed; they added that “All library employees be notified that loyalty and cordial and faithful cooperation with the librarian are essential to the welfare of the library and shall henceforth be expected of all.” Member Dockweiler, however, publicly expressed his disdain with the committee’s conclusion.

The Times noted Dockweiler’s dissatisfaction with the outcome of the investigation stating that “this investigation is regrettable in many respects...” He wrote a dissenting report with nearly two pages focusing on his disdain for Jones’ ‘slush’ comments: “the term as used in the present instance is one of contempt and it involves the sense of degradation”. He stated that the matter should have been private and placed the blame for the negative publicity on Jones. When a vote was called for a dismissal of the charges, Dockweiler was the only Board member who voted no. In a follow-up meeting, Dockweiler attempted to introduce a resolution that would give the Board of Directors control over workflow in the library effectively usurping library department heads and undermining long-established policy. Dockweiler’s resolution read “No employee of any kind whatever of this library shall absent herself or himself during scheduled or assigned hours of work without the express permission of the President or the Attendants Committee.” The resolution was not passed. He then introduced a second resolution that would establish a “book register” which the Times interpreted as “inferentially a criticism of Miss Jones.” For the time being, Jones had won this battle but she found herself in the crossfire of a very influential nemesis.