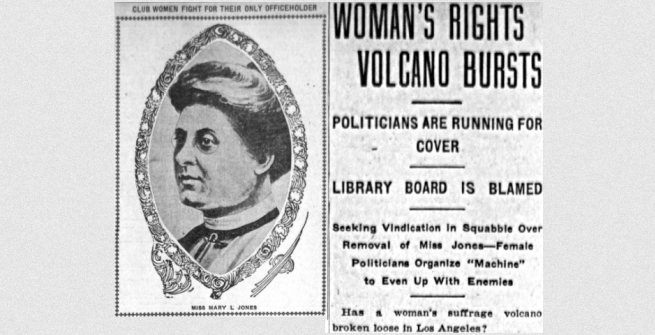

This blog post series looks at the history of the 1905 firing of Mary L. Jones as Los Angeles City Librarian. It reveals the sexism that influenced the library’s Board of Directors and shaped their decision to actively place a man, Charles Fletcher Lummis, at the head of the Los Angeles Public Library; their decision would set off a firestorm across the city.

Support for Jones in the wake of her termination was swift and thunderous. Los Angeles Women’s groups in particular came to her aid including the influential Friday Morning Club. The Friday Morning Club was probably the largest organization in Los Angeles committed to the political and social advancement of women and they immediately challenged the board and Mayor McAleer on the decision to fire Jones in favor of Lummis. On June 24th, the group forced McAleer’s hand; he promised that there would be an investigation regarding the situation but he refused to remove the offending board members as the Friday Morning Club had demanded. The following day, however, the Mayor reversed himself and decided there would not be an investigation unless he decided that the matter warranted one.

Melvil Dewey came to Los Angeles to support Jones and had a very public confrontation with Charles Lummis over the matter. Lummis also became persona-non-grata with most of the Los Angeles Women’s groups for what they felt was his collusion in the matter. Lummis, in a very awkward position, made it known that the board gave the impression that the position would be vacant. He claimed that he was not aware that Jones was being terminated in favor of himself and he denied actively campaigning for her position. In his book on the history of the Los Angeles Central Library, Kenneth Breisch states that this wasn’t the case. Publicly, Lummis did support Jones, however Breisch maintains that Lummis was friendly with Dockweiler and was, in fact, complicit in removing Jones from the position. Lummis believed that the library should be run by a man and, despite his lack of qualifications, he was certain that he was the man for the job.

Jones was under legal advisement that she keep performing her duties as City Librarian until the situation was cleared up. She spoke to the press and suggested that city officials invite librarians who were attending the upcoming American Library Association Conference in Oregon to come to Los Angeles to evaluate her abilities as librarian. On June 27th, Jones finally turned her keys over to the Assistant Librarian, Celia Gleason, officially ending Jones’ tenure at Los Angeles Public Library; Lummis was supposed to take office the next day. Lummis, however, informed the board that he would be unable to take office until September 1st and was granted a leave of absence. Gleason maintained control over the library in the interim.

The Chamber of Commerce, the Municipal League and the Merchants and Manufacturers Association added their voices to the growing chorus prodding McAleer to take action on an investigation. The Friday Morning Club began voicing their frustration with Mayor McAleer and began pushing the City Council to take action on the matter. On July 24th, McAleer finally capitulated to the avalanche of criticism and the investigation was scheduled to begin July 27. When the investigation commenced in the City Council Chambers, McAleer found himself before a standing room only crowd that included suffragettes Anna Shaw and Susan B. Anthony. The pair had arrived in Los Angeles on their way back from a meeting of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. Anthony was quoted as asking:

"I wonder why it is that the City of Los Angeles can afford to pay Mr. Lummis one hundred dollars a month more than Miss Jones without even trying him. How has be proved himself a hundred dollars a month more valuable than the woman whose place he will take?” She added that “No woman stands an equal chance with a man for a position where honor and money are concerned.”

Even Dockweiler began to backtrack under the pressure telling the Times “If Miss Jones could act as assistant librarian, or even as second assistant under the forceful direction of a superior, I believe that she could be of considerable usefulness to the library.”

Los Angeles Herald, June 13, 1895

McAleer opened by stating that the board “should be required to submit evidence in support of charges upon which they acted in removing Miss Jones.” This statement, of course, was a contradiction of his previous statements advocating placing a man in the position of City Librarian as well as his statement to the board that he had evidence of her ‘playing politics’ that would justify Jones’ removal from the position. The board, realizing the Mayor’s betrayal, and political maneuvering refused to participate and the meeting was adjourned. On July 31, McAleer asked the City Council to approve the removal of the four Library Directors who fired Jones. The four vowed to fight the mayor and asked the City Council for a formal inquiry. The City Council hesitated to get involved but near the end of August they had no other choice. But that’s another story, for another time.

Mary L. Jones ultimately weathered the storm and, after leaving Los Angeles, relocated to Berkeley where she taught at the university for two years. She relocated to Bryn Mawr where she served as librarian for six years. When she returned to Los Angeles, it was at the request of her friend and former colleague, Celia Gleason who was working to organize the Los Angeles County Public Library system. Jones spent the remainder of her career at the County Library system, allowing for a year long respite where she helped establish a library at the Camp Kearney military base during WWI. She spent her retirement years living in South Pasadena with her brother, sister and nephew. She passed away in 1946.