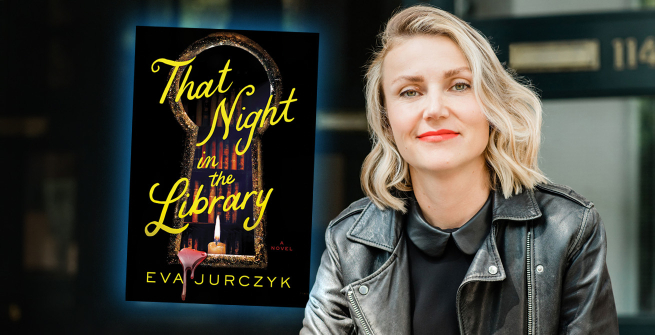

Eva Jurczyk is a writer and librarian living in Toronto. She has written for Jezebel, The Awl, The Rumpus, and Publishers Weekly. Eva smashed onto the mystery scene in 2022 with her debut, The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections—a Buzz Books, IndieNext, LibraryReads, and Canadian Loan Star pick. This summer, she sets the charming whodunnit aside to play with the Persephone myth in an A24-esque locked-room murder mystery entitled That Night at the Library and she recently talked with Daryl Maxwell for the LAPL Blog.

What was your inspiration for That Night in the Library?

There’s a lot of And Then There Were None DNA in this book. Agatha Christie didn’t invent the locked room mystery, but this particular formulation—a group with a variety of backgrounds, socioeconomic levels, pulled together in an atmospheric setting—I learned to love a locked room story based on the way Mrs. Christie wrote them.

As a graduate student, I worked in a rare book library and spent much of one summer in that library’s basement. Based on that experience, I used to go around telling my writer friends that one of them should write a locked room mystery set in a library basement. So the pieces were rolling around for a while but it wasn’t until a friend sent me an article about the science of rare books that I knew I had to write this book. I can’t talk much about the article without spoiling the story, but you’ll get my meaning when you get to the last page.

Are Davey Faye, Kip, Mary, Ro Soraya, Umu, or any of the other characters in the novel inspired by or based on specific individuals?

At my day job, I’m lucky enough to work with a team of graduate students. Unfortunately, they’re uniformly lovely, intelligent, thoughtful, and collaborative, so they’re no good to me as fodder for fiction!

How did the novel evolve and change as you all wrote and revised it? Are there any characters, scenes, or stories that were lost in the process that you wish had made it to the published version?

Call me lazy, but I’m more likely to write too short than I am too long, so I’m usually adding material in edits, not cutting it. My editor wanted me to cut the backstory for the William E. Woodend Library since it doesn’t relate to the main narrative, and it’s the only time I can think of that I haven’t taken an editorial note. My editor was probably right—the history section has taken some punches from Goodreads reviewers—but I still love it as a weird aside.

The biggest change from draft one to the final book is the use of multiple narrators. When I imagined this book, I thought it would be Faye telling the whole story. The introduction of multiple narrators happened at first because I needed to solve a problem. I’d written scenes that Faye couldn’t have witnessed. In the end, the move to multiple narrators was a gift. More weirdo backstory for me to explore! Umu and Ro’s friendship, for example. I couldn’t have fleshed that out if I’d stuck with Faye’s point of view, so I’m grateful I made the decision to divert from my original plan.

How familiar were you with Greek myths and rituals prior to writing That Night in the Library? Did you need to do some research? If so, what was the most interesting or surprising thing that you learned during your research?

I’d say I had a pretty surface level of familiarity with the Greek myths (my Catholic school education was heavy on the Gospels, light on the Greek myths), but in the early days of writing the book, I took a family holiday to Greece and bought my son a children’s book of Greek myths to get him excited for the trip. I’m not sure if you know this, but young children are rarely satisfied to hear a story only once, so I read the children’s (i.e., without the sexy bits) versions of the stories over and over that summer. Once I decided I wanted to write about the Eleusinian Mysteries, I relied on two books, The Road To Eleusis by R. Gordon Wasson, and Eleusis and the Eleusinian Mysteries by George E. Mylonas. The most interesting thread in the research, in Wasson’s book, was that the sacred potion given to participants in the course of the ritual contained a psychoactive entheogen. Not exactly magic mushrooms, but not not magic mushrooms. It made it hard for me to think of the Mysteries conducted at Eleusis as anything but Burning Man but for Ancient Greece.

Is the William E. Woodend Rare Books Library inspired by or based on a real library?

The library where I’ve spent most of my career is a Brutalist structure in the middle of a city that’s only about fifty years old. It’s also enormous, very different from the Woodend library in the book. I’m enchanted by the ivy-covered brick of small liberal arts colleges in the American woods, but the best inspiration was right on my doorstep.

One of the library buildings on our campus, University College, started construction in 1853, and everyone insists that it’s haunted. Probably with good reason. I walked those halls and listened to those ghosts when I was working on my book.

You provide the Woodend Library with a rather spectacular origin story. What’s the most sensational beginning you know of for a real library?

So, back to the story of University College’s construction in 1853 and the ghosts that came about as a result. When it was first constructed, an international group of stonemasons was hired to build the Norman Romanesque-style structure. Ivan Reznikoff, a Russian, almost immediately came to blows with Paul Diablos, an American. It might have started as a disagreement about politics or a clash of personalities, but then Diablos decided to play dirty, and he stole Reznikoff’s fiancé.

The story goes that when Reznikoff found out he’d been cuckolded, he came to the construction site with an ax, thirsty for his romantic rival’s blood. There was a chase and a struggle, and in the end, Diablos took not only Reznikoff’s lady but also his life. He stabbed him to death (in self-defense!) with a dagger he’d concealed on himself.

Reznikoff’s body wasn’t found, and Diablos was never heard from again, so for a long time, it was shrugged off as a myth.

Except in 1890, lamplighters accidentally set the building ablaze. The fire destroyed the library, and most of the collection of 30,000 books, including a 1491 edition of Dante’s Divine Comedy, were lost in the blaze. And what did they find in the rubble? A man’s remains, built into the stone walls.

You currently work for the University of Toronto Libraries. Your first novel, The Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, revolves around the theft of a valuable manuscript from a university library, and your new book, That Night in the Library, is about an unauthorized meeting in the university library that goes horribly, horribly wrong. What’s the most memorable or scandalous occurrence at the University of Toronto Libraries while you’ve been working there? Something that pre-dates your tenure?

Imagine I used this interview to reveal a tale of some spectacular, never-before-heard-of scandal at the library? I’m just irresponsible enough to do that, but unfortunately the most dramatic thing that’s happened since I’ve been there was when the library’s cafeteria got rid of the pasta station. People still haven’t recovered from that one. I’m told that back in the day, it was a pretty raucous workplace (not coincidentally, this was back when workplaces still had Friday afternoon gin and tonics in the breakroom), but I’ve never been able to get any of the longtime library staff to give me the dirt.

What’s currently on your nightstand?

I’m in recovery from my Dolly Alderton phase so you’ll find the stack of Ghosts, Good Material, and Everything I Know About Love that I read in rapid succession over the last few weeks. Hanif Abdurraqib’s There’s Always This Year that I picked up on a recent trip to Columbus, Ohio, when I learned he was the patron saint of that particular city and then was delighted to learn was about basketball. Lastly, the new Netflix show Ripley put me in a Highsmith stupor, and I’m currently on Those Who Walk Away.

What is the last piece of art (music, movies, TV, more traditional art forms) that you've experienced or that has impacted you?

There are a few pieces of art I hold in my back pocket for when I need to feel big feelings. The Google Chrome commercial "Dear Sophie," Mark Rothko’s Orange, Red, Yellow, and a 2019 BBC Radio audio production of The Merchant of Venice in which Andrew Scott (the hot priest) plays Shylock. It’s not my favorite play, but the intimacy of that great actor demanding a pound of flesh right in your earbuds as you walk alone on a gray day through a rainy city? I replayed The Merchant of Venice recently when I was in a funk and needed to press on the bruise, and it remains to transport, even on the third listen.

What are you working on now?

I have a new book out next year, another locked-room thriller. This time, a novelist struggling with writer’s block boards a train from Toronto to Montreal in the hopes of using that confined space and fixed timeframe to do some writing. A violent snowstorm traps the train in the woods, and one of the passengers is found dead. Another Christie-ish setup, but the story doesn’t go where you think it might. I’m polishing up what I hope is the final draft now. My fingers are crossed that the wintery Montreal setting means my editor will let me retain some of the Canadianisms she’s been edited out of my work for years, and I’ll finally get to teach my American readers that it’s a toque, not a beanie.