By the late nineteenth century, the West Coast of the United States was home to thriving Japanese communities. After the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 barred the immigration of Chinese workers, Japanese laborers were sought for many industries, including agriculture and fishing. By the early 1900s, numerous Japanese women had come to the United States to join their husbands and start families. Locally, two Japanese communities thrived: Little Tokyo, near downtown Los Angeles, and the fishing community on Terminal Island, known as Fish Harbor. Rafu Shimpo, the oldest Japanese language newspaper in the United States, began publishing in 1903. Temples and churches were built, and a Japanese American Chamber of Commerce was established.

Everything changed for Japanese Americans on December 7, 1941, when Japanese aircraft attacked the American naval base at Pearl Harbor. Japanese Americans quickly fell under suspicion, regarded as spies or saboteurs. Their loyalty was questioned, regardless of citizenship. On February 19, 1942, Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which ordered the removal and incarceration of West Coast residents of Japanese descent.

A civilian organization called the War Relocation Authority quickly established a network of Assembly Centers and Relocation Centers. Families were given six days to put their belongings in storage and report to an assembly center, bringing only what they could carry. Assembly centers were often on racetracks or fairgrounds. Families would live in converted horse stalls or in fairground halls.

Families would eventually be assigned to a relocation center, where they lived for several years. These were effectively prison camps where families would share barracks. Kitchens and latrines were communal. Relocation centers were also like small towns, with post offices, schools, and worksites for adults. Often there was space for livestock and crops. These camps tended to be in isolated, barren areas with freezing winters and hot summers. The prison camps were surrounded by barbed wire and watched over by guards in towers. One of the most famous relocation centers is Manzanar, about 200 miles north of Los Angeles. Today, it is a historic site managed by the National Park Service.

Over 100,000 Japanese Americans, most of them American citizens were sent to relocation centers far from home, where they were forced to live in difficult, uncomfortable conditions. Family pets had to be left behind. Numerous children spent several of their formative years in camps surrounded by barbed wire. Families lost their homes, their businesses, and most of their belongings. The last of the relocation centers did not close until March 1946.

George (left) and James Toya at the Tule Lake internment camp, 1945. Shades of L.A.: Japanese American Community

Following the evacuation of the Japanese, the Los Angeles neighborhood of Little Tokyo was empty. African Americans began moving into Little Tokyo, trying to avoid segregation laws that restricted where they could live and establish businesses. Little Tokyo became known as Bronzeville. New businesses included jazz clubs, bars, and restaurants. After the war, African Americans moved out and, over time, Little Tokyo thrived again as a vibrant Japanese community.

It is essential that we continue to remember the experience of Japanese Americans during World War II. Sadly, very few people who lived through this ordeal are still alive to tell their stories. The Little Tokyo Historical Society and the Japanese American National Museum are two local institutions that preserve and honor the Japanese American experience of World War II. The History Department at the Los Angeles Public Library Central Library has an extensive collection of books about the Japanese American Internment, including personal memoirs and pictorial works. The following titles are representative of the History Department’s broad and evolving collection.

Citizen 13660

Published in 1946, Citizen 13660 is one of the earliest and one of the most famous first-person accounts of life in the internment camps. It is also one of the first examples of what is now known as a graphic novel. In this book, Mine documents her family’s experiences in relocation centers in California and Utah. 13660 is the identification number assigned to her family. Okubo’s drawings illustrate the conditions in the camps, including spiders and mice in the barracks, the lack of hot water in laundry centers, and the lack of privacy in the latrines.

Looking Like the Enemy: My Story of Imprisonment in Japanese-American Internment Camps

Mary lived her early life in a Japanese island community just north of Tacoma, Washington. She was seventeen years old when her family was assigned the number 19788 and removed from their community. They lived in several relocation centers in California, Wyoming, and Idaho. She describes her fear when she arrived at a relocation center and saw that the barbed wire was facing inward. They were not being sent to camps for their protection, as they had been told. They were prisoners.

A little Japanese child meekly submits to a hair wash while a woman nearby also washes her hair at the Santa Anita Assembly Center, [1942]. Herald Examiner Collection

Farewell to Manzanar: A True Story of Japanese American Experience During and After the World War I

Houston, Jeanne Wakatsuki

First published in 1973, Farewell to Manzanar has become a classic work, widely taught in schools. Jeanne was seven when her family was ordered to close their fishing business and leave their Long Beach home with only what they could carry. She writes of attempts at normalcy in Manzanar, including dances and a dance band, and sports teams. She also describes the lack of space and privacy. Her father struggled with drinking. He was arrested and sent to a prison camp in North Dakota for a year before rejoining the family at Manzanar. After three years in Manzanar, the Wakatsuki family returned to Long Beach and lived in public housing. Wakatsuki Houston was inspired to write her memoir when she returned to Manzanar with her husband in 1972.

Desert Exile: The Uprooting of a Japanese-American Family

Yoshika Uchida was born in Alameda, California and raised in Berkeley. During her senior year at U.C. Berkeley, her family was sent to the assembly center at the Tanforan Racetrack, just south of San Francisco. They lived in converted horse stables for several months before being sent to the Topaz Relocation Center in Utah. Like Manzanar, Topaz was hot in the summer and bitterly cold in the winter. Housing was hastily constructed and inadequate. Latrines were shared and lacked basic privacy features, such as stall dividers. Yoshiko’s experience there shaped her future. In 1971, she wrote a children’s novel called Journey to Topaz, based largely on her experience there. She went on to write numerous children’s books based on the Japanese American experience.

Gasa Gasa Girl Goes to Camp: A Nisei Youth Behind A World War II Fence

Lily was born in Los Angeles. When she was ten years old, her family was sent first to the Santa Anita assembly center and then to the Amache Relocation Center in Colorado. Her memoir of her time in the camp includes water colors, family photos, and drawings. She writes of the difficulty of approaching adolescence in the camp, and of her conflicting emotions over her identity as an American of Japanese descent. Her memories include a birthday celebration featuring a cake made of crackers, peanut butter and jam.

Adios to Tears: The Memoirs of a Japanese-Peruvian Internee in U.S. Concentration Camps

Seiichi Higashide brings a unique perspective to his memoir. He was born in Japan and emigrated to Peru in 1931. At the outbreak of World War II, he and other Latin American Japanese were deported to the United States. He was held at the Immigration and Naturalization facility in Texas for over two years. After the war, he became an American citizen and was active in the movement seeking reparations for Japanese American internees.

Yuki (left) and Aki Toya in front of their barracks at the Tule Lake internment camp, [1945]. Shades of L.A.: Japanese American Community

My Life in Camps During the War and More

Saito wrote this book for his nieces and nephews, so that they would know what their family had experienced during World War II. He was eight years old when his family had to carry their belongings to a storage facility. They were put on a train headed from their hometown of San Jose to the Santa Anita Assembly Center near Los Angeles. The family, assigned the number 32418, lived in horse stall barracks and slept on mattresses filled with straw. His relatives were eventually split up. He and his immediate family were sent to Heart Mountain, Wyoming. He speaks of the freezing conditions and having to eat standing up in the mess hall. Families from California were not equipped for the Wyoming climate. He states: “We are locked away by the Federal government, who think we may be spies for a foreign country that most of us have no ties with.”

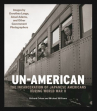

Un-American: The Incarceration of Japanese Americans During World War II

The Federal government hired photographers to document the process of Japanese Americans being moved from their homes to internment camps. Among these photographers was the noted photojournalist and photographer, Dorothea Lange. Ansel Adams, perhaps best known for his images of Yosemite, obtained permission to photograph inside Manzanar. He later stated that his Manzanar photos were his most important work. This book collects 170 poignant black and white images taken before, during, and after the relocation of Japanese Americans. Lange photographed families in front of their homes and on their farms shortly before they would be forced to leave, highlighting all that was left behind. Numerous photos show the conditions in the camps and document daily life, including weddings and funerals.

Colors of Confinement: Rare Kodachrome Photographs of Japanese American Incarceration in World War

Manbo and his family were forced to leave their Hollywood home and were eventually sent to the relocation center in Heart Mountain, Wyoming. He used his Kodak camera to take rare color photographs of life inside the camps. Many of these photographs show normal daily life: parades, sports events, and children playing. The guard towers and the barbed wire are reminders that the subjects of these photographs were prisoners.

Panoramic view of Heart Mountain Relocation Center, the WWII Japanese American internment camp in Wyoming, [ca 1943]. Shades of L.A.: Japanese American Community

![Panoramic view of Heart Mountain Relocation Center, the WWII Japanese American internment camp in Wyoming, [ca 1943]. Shades of L.A.: Japanese American Community](https://www.lapl.org/sites/default/files/styles/blog_feature_image/public/blogs/2022-05/heartmountain.jpg?itok=XtOANjXb)