As we observe Asian Pacific American Heritage Month at Los Angeles Public Library, this is a good occasion to look at some of the interesting examples of Japanese cinema available to our patrons, particularly those featuring scores by composer Tôru Takemitsu. Films with soundtracks by Takemitsu are available to LAPL patrons in our DVD collection, and on Kanopy, the library's new online service.

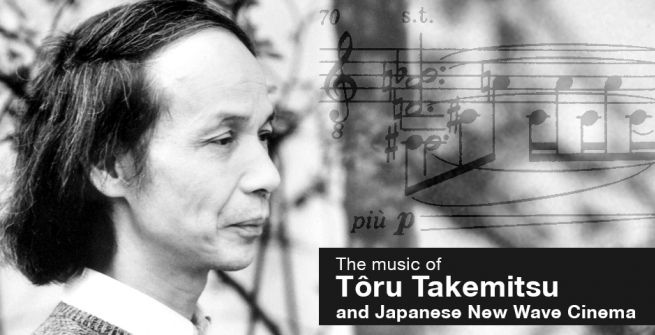

Tôru Takemitsu (武満徹; 1930-1996) was the most successful Japanese composer of the 20th century, and arguably the most internationally-renowned postwar Asian composer. Self-taught as a composer, Takemitsu wrote scores for the concert hall, film, television and commercials, and also found time to write poetry, books on music theory, and a detective novel. He even appeared as a celebrity chef on television programs. Outside Japan Takemitsu is known mainly for his over 130 "serious" concert works, however, he was a prolific film composer, writing over 100 soundtracks. Most films with Takemitsu scores available through Los Angeles Public Library are those in which he collaborated with directors of the Japanese New Wave.

The Japanese New Wave began among younger directors in the major film studios in the late 1950s as a reaction against the older, traditional style of Japanese cinema represented by such masters as Yasujirô Ozu and Kenji Mizoguchi. The New Wave made a significant impact on Japanese cinema of the 1960s and 1970s, and left a lasting influence on world cinema. The Japanese New Wave was concurrent with the French New Wave after which it was retroactively named. The French New Wave in film is usually said to have begun in 1958, with Claude Chabrol's Le Beau Serge (1958), two years after the release of Crazed Fruit (1956), the film generally considered to have launched the Japanese New Wave.

Much of Takemitsu's childhood was spent in Japan-occupied Manchuria. By the last year of the war, Takemitsu was back in Japan stationed in an underground fortress west of Tokyo. Takemitsu recalled his moment of musical awakening when an officer played a record of Lucienne Boyer singing "Parlez-Moi d’Amour". Heard in the midst of the oppressively monotonous work where only patriotic songs were allowed, the song gave a brief glimpse into a new world of musical possibilities to the 14-year-old Takemitsu.

A sickly, introverted child, Takemitsu spent the post-war years of Allied occupation exploring this previously unavailable musical world on the radio, and through his father's collection of American jazz records. Rather than follow his father's wishes for him to become a businessman, he decided to pursue a life in music. Lacking a formal musical education, Takemitsu often claimed that Duke Ellington was his only teacher. Besides jazz, Takemitsu immersed himself in western classical and contemporary concert music. The French composers Claude Debussy and Olivier Messiaen, as well as Schoenberg, Webern, and the Second Viennese School were especially strong influences on Takemitsu's early musical aesthetic. His experiences during the war left Takemitsu with an aversion to the native artistic traditions of his homeland. Several of the New Wave film directors with whom he collaborated also used their art to criticize aspects of Japanese society. Takemitsu later wrote, "Because of World War II, the dislike of things Japanese continued for some time and was not easily wiped out. Indeed, I started as a composer by denying any 'Japaneseness.'"

Takemitsu's career as a composer began with his participation with the multi-media group Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop). In the 1950s he served as assistant to the film composer Fumio Hayasaka (1914-1955), who composed the scores to some of the greatest Japanese films of the decade, including Kenji Mizoguchi's Ugetsu Monogatari (1953) and Sansho the Bailiff (1954), and Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1950), Ikiru (1952), and Seven Samurai (1954). After Hayasaka's death at the age of 41, Takemitsu composed his Requiem for Strings (弦楽のためのレクイエム; 1957) in his mentor's memory. Visiting Japan in 1958 Igor Stravinsky was impressed after hearing this composition on the radio, and spoke well of Takemitsu in interviews. Takemitsu's fame spread and international concert music commissions followed. Decades later, when he collaborated with the great director Shôhei Imamura—a leading figure in the Japanese New Wave—on Black Rain, Imamura's 1989 film on the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Takemitsu wrote a score utilizing and expanding on his Requiem for Strings Unfortunately this film is not currently in the library's collection.

An encounter with American composer John Cage and his Zen-inspired work helped inspire Takemitsu to re-examine Japanese aesthetics. Cage had a profound impact on Takemitsu by imparting a positive view of Japanese tradition, divorced from the repressive, militaristic attitudes with which Takemitsu had associated with Japanese traditions during the war years. About this time he also gained an appreciation of traditional Japanese puppet theater—bunraku. Of this period, Takemitsu said, "I got a shock… I suddenly recognized I was Japanese," and, "I came to recognize the value of my own tradition."

A watershed moment in Takemitsu's career came in 1967 with a commission for the 125th anniversary of the New York Philharmonic. For this occasion, he composed November Steps, in which the Japanese traditional instruments, the biwa and the shakuhachi, perform with the western orchestra. Indeterminacy was another of Cage's interests that Takemitsu experimented with, however, Takemitsu's use of performer improvisation is tightly controlled, more in the style of Polish composer Witold Lutosławski than Cage. In November Steps he allows the Japanese instrumentalists to improvise based on graphic notation, while the western orchestra is notated in traditional western fashion. This work solidified Takemitsu's international fame among audiences of contemporary music.

A quiet and reserved man, Takemitsu's conversation, like his music, tended to include long pauses and silences. He was a passionate film-goer, regularly attending over 300 movies a year, and friends reported that a little alcoholic stimulation could inspire Takemitsu to entertain them with an endless recitation of the plots of obscure B-movies. Besides his natural love of cinema, Takemitsu noted from a practical point of view that a single film score could expose his music to a much larger audience than he could ever hope for with a concert performance.

Takemitsu's lighter popular music is well-known Japan, while outside the country he is better known for his avant-garde and experimental music, and for blending Eastern and Western traditions. Most of the DVDs in the library's collection featuring Takemitsu soundtracks are more modernist scores he wrote for directors associated with the Japanese New Wave. Below are some of the films in the library's collection which he made with these directors.

Kô Nakahira

Takemitsu's first feature film score was for director Kô Nakahira (中平康)'s 1956 version of Crazed Fruit (Kurutta kajitsu), based on Shintarô Ishihara's novel of youthful rebellion, ennui and nihilism among well-to-do youth of the post-war years. With fellow Fumio Hayasaka protege, Masaru Satô, Takemitsu produced a jazzy score with saxophones, muted trumpets and sliding electric guitars. Satô's first film score was for the first Godzilla sequel, Godzilla Raids Again (1955). He provided the scores for three more Godzilla films, the Jun Fukuda-directed Godzilla vs. the Sea Monster (1966), Son of Godzilla (1967), and Godzilla vs. Mechagodzilla (1974). Along with these Satô is probably best known to Western audiences for his similarly jazz-influenced scores for such classic Akira Kurosawa films as Yojimbo (1961), Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958) and Sanjuro (1962).

The success of Crazed Fruit inspired the Taiyozoku, or "Sun Tribe" genre, depicting the lives of Japan's post-war generation. Along with the popularity of these films came scandal, protests, and demand for censorship. Though the studios stopped making films in the Taiyozoku genre, their influence on Japanese film was permanent, and they are cited as the beginning of the Japanese New Wave of the 1950s and '60s.

Through this film and further youth films at Nikkatsu, director Nakahira helped establish the irreverent, iconoclastic, auteur-centric style that was to mark the Japanese New Wave. His career was hampered by personal problems, and by the '60s he was directing films under an alias for the Shaw Brothers studio in Hong Kong, sometimes remaking his earlier Japanese successes for Chinese audiences. Takemitsu went on to be closely associated with the work of several major directors in the Japanese New Wave.

Hiroshi Teshigahara & Kôbo Abe

Director Hiroshi Teshigahara (勅使河原宏; 1927-2001), an accomplished artist in several media, was the descendant of an old and wealthy family. His father, Sôfu Teshigahara (勅使河原蒼風; 1900-1979), was the founder of the Sôgetsu school, a major, innovative school of flower arranging (ikebana), and, though he did not pressure his son to do so, expected that Hiroshi would eventually take over the family business. Hiroshi first aspired to be a painter and also worked successfully in pottery and calligraphy. During the post-war years in Japan, it was common for young artistically-inclined people to gather in coteries to discuss the future direction of the society. Takemitsu had been part of such a group, Jikken Kobo ('Experimental Workshop') for music, dance, and multi-media, and Teshigahara also hosted such events, concerts, and exhibitions at his father's studio. Besides bringing him in contact with Abe and Takemitsu, these gatherings attracted such international artists as Robert Rauschenberg, Yoko Ono, Shuji Terayama, Merce Cunningham, and John Cage. Teshigahara emphasized film in these events, and by making his own short films eventually became a pioneer as an outsider breaking into Japan's closed, studio-dominated film industry. Takemitsu wrote the music to all Teshigahara's films. Teshigahara's Woman in the Dunes made him an internationally celebrated director. However, after directing several classics of the Japanese New Wave, Teshigahara abandoned film to take over as head of the family flower arranging school after his father's retirement.

Writer Kôbo Abe, like Takemitsu, came from a less privileged background than Teshigahara, spending his formative years in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. His years in this desert surrounding had a profound impact on Abe's writings, and his sense of alienation from society persisted after his return to Japan. He commented, "I remained in Manchuria for a year and a half after the war and witnessed the complete destruction of social order there. That made me lose all trust in anything stable."

With Teshigaraha and writer Kôbo Abe, Takemitsu collaborated on four films important to the Japanese New Wave, experimenting with avant-garde style and exploring themes of alienation in modern society: Pitfall (1962), Woman in the Dunes (1964), The Face of Another (1966), and Man Without a Map (1968). The first three of these films are part of the library's collection. Having known and worked with each other since the 1950s, before their first film collaboration, the group knew each other's interests, styles, and themes. In the making of the films, each artist made contributions to the whole beyond their individual roles as director, screenwriter, and composer.

After Takemitsu's death, Teshigahara remarked, “He gave me much more than just music. He gave me ideas and energy and a kind of trust that never failed. He was always more than a composer. He involved himself so thoroughly in every aspect of a film—script, casting, location shooting, editing, and total sound design—that a willing director can rely totally on his instincts.”

The trio's first collaboration, Pitfall (Otoshi ana; 1962) was a low-budget production, a Kafkaesque story of a miner and his son on the run from forces unknown to the audience for reasons unknown to the audience. Straight-faced mixing of realistic and supernatural elements, as well as disregard for linear narrative and disdain for conventional genre plot points, add to the unsettlingly surrealistic nature of the film.

Takemitsu was forced to exercise his creativity within the limited resources available to him in an independent production. By employing a prepared piano he was able to give the soundtrack an unusual and varied sonic texture with only one musician. The pianist produces various unusual sounds by strumming and plucking the strings of the piano, knocking against the wood, etc. These sounds, along with vocalisms, are sometimes electronically altered, creating a sparse, disorienting yet varied sound world which reflects well on the existentialist themes of the film.

The second film made by Teshigahara, Abe and Takemitsu, Woman in the Dunes (Suna no onna; 1964), is Teshigahara's best-known and most successful film, and one of the major Japanese film of the 1960s. The film relates the story of a Tokyo entomologist who becomes trapped at the bottom of a sand dune with a young widow. His struggle to escape and the couple's difficult existence and relationship allow Teshigahara to use his strikingly sensual and tactile black and white images, Abe's existentialist screenplay and Takemitsu's eerie soundscapes to observe the human condition and the relation of the individual to society through. The Woman in the Dunes became an international art-house hit and garnered Teshigahara a nomination for Best Director at the U.S. Academy Awards.

Takemitsu's score for the film relies heavily on the modernist musical style for which he was known in concert halls, played mostly on string instruments. Besides advanced instrumental techniques, such as mass glissandi, and percussive effects, the instruments are also given electronic enhancement and distortion. Takemitsu later used some of the musical ideas in The Woman in the Dunes for Dorian Horizon (1966) a concert piece for 17 strings. By placing the instrumentalists at distances from each other, a live performance of this work gains a spatial dimension. Dynamic shadings, according to Takemitsu, are less discernable in instruments spaced apart from each other, but the timbre or sound color between a forte and a piano is different. This spatial arrangement created what Takemitsu termed a 'musical garden'. Takemitsu further explored concepts related to Japanese gardening in later concert works such as In an Autumn Garden (1973) Garden Rain (1974), and A Flock Descends into the Pentagonal Garden (1977).

The trio's third film together, Face of Another (Tan'in no kao; 1966), is a metaphorical examination of identity through the story of a man who is disfigured and, through surgery, given the face of a stranger. Alienated from his wife, his friends, and his family, the man's personality begins to change radically as he finds himself adopting a new persona.

Through the use of contrasting traditional and experimental film techniques, Teshigahara reflects the contrasting double-nature of the main character. Stylistically a modernistic film, Teshigahara employed old-fashioned square aspect ratio and black and white, at a time when color and wide-screen formats were common in Japan. As if to emphasize that the use of the aspect ratio is intentional, Teshigahara briefly lapses into wide-screen just long enough to introduce one character. A fourth collaborator on this film, the architect, Isozaki Arata, a friend of Teshigahara's, designed the strange objects which populate the film.

In contrast to the avant-garde music Takemitsu composed for the trio's previous films, for Face of Another (1966), he showed his affinity for popular music by writing a deliciously lush and catchy Viennese waltz. Given Takemitsu's reputation for cutting-edge, electronic-music enhanced soundtracks, the blatantly traditional nature of the theme clashes with the ostentatious camera work, editing and other techniques Teshigahara uses in the film. Further emphasizing the film's penchant for contrasting doubles, Takemitsu's theme is played instrumentally, and also given a vocal performance by a chanteuse who croons the waltz with German lyrics in a beer hall scene, accompanied on accordion.

Audiences who knew Takemitsu only for his avant-garde concert scores were sometimes put off by the unapologetically schmaltzy side he could display in popular-based music such as this. American director Jim Jarmusch, for example, hired Takemitsu to compose a score for his film Night on Earth (1991) but rejected the pop-sounding score. Takemitsu's wife believes this may have been because Jarmusch had expected the modernistic sounds of The Woman in the Dunes or Kwaidan.

Takemitsu wrote the music to all of Teshigahara's films including those made without Abe as screenwriter. The library has the DVD to Antonio Gaudí, a documentary Teshigahara made in 1984 as a return to film after. Teshigahara had first encountered the work of Catalan architect Antonion Gaudí in 1959 while traveling to America and Europe with his father. It was Spain and specifically Gaudí's work which made the strongest impression on Teshigahara on this trip. For this wordless visual documentary exploration of Gaudí's world, Takemitsu wrote an aurally varied score utilizing many styles, from European Medieval music to the avant-garde. It is a sparse, but romantic score, utilizing the ethereal sounds of the glass harmonica and metallic percussion, electronic sounds, traditional orchestral instruments and musique concrète such as sounds of the wind, traffic, and the ocean.

Masaki Kobayashi

Masaki Kobayashi (小林正樹; 1916-1996) is another major director of the Japanese New Wave whose films are in the library and with whom Takemitsu frequently collaborated. Kobayashi was born in the port city of Otaru, on the northern island of Hokkaido, and, after a university education in Tokyo, began his film career in 1941 as an Assistant Director at Shochiku studio. One of Japan's six major film studios, Shochiku was founded in 1895 as a kabuki company, and began making films in 1920. Eight months after joining the studio, Kobayashi was drafted into the army and was sent to Manchuria. He protested the war—which he called “the culmination of human evil”—by refusing promotions in rank and the relative comfort that would have come with them. Kobayashi finished his military experiences as a prisoner of war in Okinawa, and returned to Shochiku studio after his release in 1946. Along with Akira Kurosawa, Kobayashi is considered one of the post-war directors who redefined the chanbara (sword-fighting) genre. From the start Kobayashi's film work showed unfashionably strongly anti-authoritarian impulses, resulting in disputes with studio heads, and censorship of his films. As the New Wave emerged in the late '50s and early '60s, Kobayashi's work became more in tune with the spirit of the times. The studio allowed Kobayashi major productions, such as The Human Condition—(1959–61), his epic, nearly 10-hour depiction of a pacifist in the military during Japan's occupation of Manchuria. This film gave the major film actor Tatsuya Nakadai his first starring role.

Kobayashi and Takemitsu first worked together on Harakiri (Seppuku; 1962), a bitter criticism of hypocrisy and corruption in the feudal system of the early Tokugawa era (1603-1868). The story centers on a poverty-stricken ronin (masterless samurai) who, unable to provide for his family, begs to be allowed to commit ritual suicide at a lord's manor. Like other Japanese directors of the time, Kobayashi used stories from history to make observations on current life. He had directly criticized the military in The Human Condition, and in Harakiri he excoriates the feudalistic system, elliptically criticizing contemporary Japanese politics and society of the 1950s and early '60s. Harakiri was awarded the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival and was remade in 2011 by prolific and controversial director Takashi Miike, released to English-language audiences as Hara-Kiri: Death of a Samurai.

A milestone in Takemitsu's concert music career came when he combined the Japanese traditional instruments, shakuhachi and biwa, with the western orchestra in November Steps (1967). However, he had worked with Japanese instruments earlier in his film and television work. He used biwa and koto for the 1961 TV documentary Nihon no Monyou, and for Kobayashi's Harakiri and Kwaidan (1964). For the 1966 TV drama, Minamoto Yoshitsune he wrote for shakuhachi, shinobue & ryuuteki with western orchestra.

The soundtrack for Harakiri employs modernistic techniques such as tone clusters and mass glissandi in the western orchestra, played with obvious influence from the traditional Japanese aesthetics that Takemitsu had recently come to embrace in his concert music. The traditional Japanese biwa—a kind of lute often used to accompany the singing of a narrative—plays solo and with the orchestra, as well as with electronic alteration. The result is an ominously stylized rendering of a traditional Japanese sound.

Kwaidan (怪談; 1965), Kobayashi's next film, was uncharacteristically apolitical for the normally socially-conscious director. It is a slow, hypnotically stylized, colorful three-hour anthology of four ghost stories from a 1904 collection by Lafcadio Hearn, the Greek-Irish-American writer who settled in Japan. The film caused some confusion among critics on first release—Not horrifying enough to be called horror, not political enough to satisfy Kobayashi's followers at the time, intentionally stagy and artificial—nevertheless, Kwaidan is perhaps Kobayashi's best-remembered film. The most expensive Japanese film production at the time, Kwaidan is a long, mesmerizingly detailed creation of a self-contained and artificial world. The most famous segment of the film is "Hoichi the Earless", about a blind biwa-playing monk tricked into performing for a group of ghosts.

Takemitsu's score for Kwaidan uses the western orchestra along with musique concrète, noise, carefully-placed silences, and Japanese instruments to bring a quietly ominous aural dimension to Kobayashi's striking visuals and camera movement. Of his score for Kwaidan, Takemitsu stated, "I wanted to create an atmosphere of terror. But if the music is constantly saying, 'Watch out! Be scared!' then all the tension is lost. It’s like sneaking up behind someone to scare them. First, you have to be silent. Even a single sound can be film music."

For Samurai Rebellion (Jôi-uchi: Hairyô tsuma shimatsu; 1967) Kobayashi returned to the themes of the corruption of authority and the feudalistic system in particular. Toshirô Mifune plays a middle-aged samurai whose son is ordered to marry the mistress of his clan lord. After the couple are married and grow to love each other, the lord changes his mind, instigating the rebellion referred to in the film's title. Set in the early 18th century, at the mid-point of the Tokugawa shogunate, about a century after the story depicted in Harakiri, in Samurai Rebellion Kobayashi again uses historical time periods to criticize current society. Kobayashi commented, "In any era, I am critical of authoritarian power."

Besides the theme the struggle of the individual against a corrupt power structure, the film explores what Kobayashi calls "the deceit of history". The film ends with the caption, "An incident of significance has taken place while remaining unrecorded in official history, as though all were calm and nothing had ever happened."

Masahiro Shinoda

Like Masaki Kobayashi, Masahiro Shinoda (篠田正浩; b. 1931) began his career as an Assistant Director at Shochiku. He joined the studio in 1953 and made his directorial debut in 1960. Shinoda may be best known in the United States as the director of the film Silence (1971), also scored by Takemitsu, and based on the same book as the recent film of the same title by Martin Scorsese. Shinoda's early film work as an Assistant Director was mainly with light youth-based rock & roll films. Rock & roll was not associated with the Japanese New Wave style, and when he began directing, he chose Takemitsu as his composer.

Based on a story by Shintarô Ishihara, the author of Crazed Fruit, Shinoda's Pale Flower (Kawaita hana; 1964) is a dazzling, cool, nihilistic film noir about a middle-aged gangster recently released from prison who becomes infatuated with a self-destructive young woman addicted to gambling. Takemitsu gives the story of the bored, thrill-seeking woman and the weary yakuza a score with blaring jazzy horns, strange percussive effects, and his signature string clusters and glissandi, all of which are amplified and modified electronically.

Shinoda's Samurai Spy (Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke; 1965) is a stylish tale of intrigue and fighting between rival factions in the years after the Battle of Sekigahara (1600), in the early years of the Tokugawa shogunate. The film's samurai hero is an alienated individual, anti-war, but surviving in a pitilessly violent post-war world. Takemitsu provided the film a score closely related to his concert work, with western instruments in modernist style, punctuated by outbursts of jazz-influenced music.

With Shinoda Takemitsu co-wrote the screenplay to Double Suicide (Shinju: Ten no amijima; 1969), based on Monzaemon Chikamatsu's classic early 18th century bunraku puppet play, The Love Suicides at Amijima (Shinjû: Ten no Amijima). A tragedy in which two lovers commit suicide together as they cannot be united in society, Shinoda films the play in an unusual fashion. Black-masked puppeteers stand behind the actors who play the puppets' roles of the original play. Shinoda emphasizes not only the artificiality of the production but the helplessness of the individual characters' fate in opposition to society. As the tragedy of the conflict comes to a climax, Shinoda's camera focuses more on the faceless puppeteers who become tragic figures themselves, unable to prevent the impending tragedy they have set in motion.

Akira Kurosawa

Following the heyday of the New Wave in the 1960s, Takemitsu wrote scores for two later films of Akira Kurosawa (黒澤明; 1910-1998) which are in the library's collection. Dodes'ka-den (どですかでん; 1970), was one of the great director's most troubled productions. Kurosawa's first color film, it follows the lives of several people struggling to make a living in a Tokyo slum. The film's poor reception on first release led Kurosawa to attempt suicide.

Takemitsu's score is light, melodic and pop-influenced, utilizing full orchestra, ocarina, harmonica and rhythm percussion. Acoustic guitar, prominent in the soundtrack, is an instrument for which Takemitsu wrote several concert pieces, as well as a few highly-regarded arrangements of Beatles songs.

Kurosawa's previous composer, Masaru Satô, had ended his collaboration with the director, complaining of his habit of continually insisting Satô re-write his musical soundtracks. Like Satô, Takemitsu argued with Kurosawa when working on Ran (1985), his apocalyptic, late-career retelling of King Lear. Takemitsu wanted to compose a score entirely in a stylized Japanese traditional musical and vocal styles. Some of this can be heard in the finished film's score—for example in the noh flute solo performed by one of the characters on screen—however, Kurosawa insisted on a Mahler-influenced score. Takemitsu argued his dissatisfaction with the use of a western classical style in films about periods in Japanese history. But Kurosawa was not nicknamed "The Emperor" for nothing, and Takemitsu had to bend to the director's will. Nevertheless, Takemitsu wrote one of his most memorable scores, and The Los Angeles Film Critics Association gave Takemitsu the Best Music award for his work on the film.

Though his concert music is better known outside Japan, throughout his career there was a cross-influence between Takemitsu's "serious" music and his film music. The avant-garde concert music that he wrote during the 1960s fit well into the films of the Japanese New Wave directors with whom he worked. He could even rework material originally written for film scores into concert works, as in the case with the score to Woman in the Dunes and the concert piece Dorian Horizon. Films also inspired some of his concert works, such as Nostalghia (1987) named for Tarkovsky's film Nostalghia (1983). Regardless of the style in which he wrote, Takemitsu's music is preoccupied with pauses and silence, a concern directly relevant to his film work. Takemitsu noted, "timing is the most crucial element in film music: where to place the music, where to end it, how long or how short it should be."

In the post-New Wave era Takemitsu's concert music took on a longer-breathed Romantic sound which may have been partly inspired by the Mahlerian film score that he wrote for Ran, Kurosawa's last epic film. The slow, quiet, wispy sensuousness of Takemitsu's music caused some critics during his lifetime to view it as decorative lighter fare in the concert hall. However, in the years since Takemitsu's death from cancer at the age of 65 in 1996, his music has slowly been gaining a place in the standard repertoire of modern music. He is today regarded one of the major composers of the postwar years and Japan's most important composer of the 20th century.

For more Asian films, and films and videos related to Asia, please see our new online streaming service, Kanopy.

For information, programs and activities related to Asian-American Pacific Islander Heritage Month, explore the library's APAHM page.

For activities related to Asian-American Pacific Islander Heritage Month at the library, please see our Calendar of Events.

Library and Online Resources Related to Toru Takemitsu

Films on DVD at the Library with Takemitsu Soundtracks

- Antonio Gaudí

- Crazed Fruit - Kurutta Kajitsu

- Dodesuka-den

- Double suicide - Shinjû ten no Amijima

- Harakiri - Seppuku

- Pale Flower - Kawaita Hana

- Kwaidan

- Ran

- Ran

- Samurai Rebellion - Jôi-uchi: Hairyô tsuma shimatsu

- Samurai spy - Ibun sarutobi sasuke

- Three films by Hiroshi Teshigahara (Pitfall, Woman in the Dunes & Face of Another)

Resources on Takemitsu in the Library

Scores

Orchestra

- Dream/Window (夢窓; 1988)

- Green (グリーン; 1969)

- November steps (ノヴェンバー・ステップス; 1967)

- Rain coming (雨ぞふる; 1983)

- Riverrun (Piano and orchestra) (リヴァラン; 1987)

- To the edge of dream (Guitar and orchestra) (夢の縁へ; 1983)

Piano

Solo & Chamber

- Distance de fée (Violin and piano) (妖精の距離; 1989)

- Entre-temps (Oboe and string quartet) (アントゥル・タン; 1987)

- Le fils des étoiles: prélude du 1er acte "La vocation" (Flute and harp / Erik Satie; arranged by Tôru Takemitsu) (星たちの息子 – 第一幕への前奏曲『天職』 –; 1992)

- From far beyond chrysanthemums and November fog (Violin and piano) (十一月の霧と菊の彼方から; 1983)

- Itinerant: in memory of Isamu Noguchi (Flute) (巡り – イサム・ノグチの追憶に –; 1989)

- Orion (Cello and piano) (オリオン; 1984)

- Paths: In memoriam Witold Lutosławski (Trumpet) (径 – ヴィトルド・ルトスワフスキの追憶に –; 1994)

- Rain spell (Flute, clarinet, harp, piano, and vibraphone) (雨の呪文 - Ame no jumon; 1983)

- Rain tree (3 percussion players, or 3 keyboard players) (雨の樹; 1981)

- Rocking mirror daybreak (Violin duo) (揺れる鏡の夜明け; 1983)

- Toward the sea (Alto flute) (海へ; 1982)

- Toward the sea III (Alto flute and harp) (海へ III; 1989)

- A way a lone (String quartet) (ア・ウェイ・ア・ローン; 1982)

Books by Takemitsu

Books about Takemitsu

- Creative sources for the music of Tôru Takemitsu (1993) by Noriko Ohtake

- The music of Tôru Takemitsu (2001) by Peter Burt

- "Tōru Takemitsu's Collaborations with Masahiro Shinoda: The Music for Pale Flower, Samurai Spy and Ballad of Orin" by Timothy Koozin, in The Cambridge companion to Film Music

Further reading on the Japanese New Wave

Online Articles

Criterion articles

- Antonio Gaudí: Border Crossings by Dore Ashton

- Crazed Fruit: Imagining a New Japan—The Taiyozoku Films by Michael Raine

- Dodes’ka-den by Barbara Scharres

- Dodes’ka-den: True Colors by Stephen Prince

- Double Suicide by Claire Johnston

- The Face of Another: Double Vision by James Quandt

- Harakiri: Kobayashi and History by Joan Mellen

- Kwaidan: No Way Out by Geoffrey O’Brien

- Pale Flower: Loser Take All by Chuck Stephens

- Pitfall: Outdoor Miner by Howard Hampton

- Ran: Apocalypse Song by Michael Wilmington

- Samurai Rebellion: Kobayashi's Rebellion by Donald Richie

- Samurai Spy: The Thin Line Between Truth and Lies by Alain Silver

- Woman in the Dunes: Shifting Sands by Audie Bock

Other articles on Takemitsu's film work

- The collaborative films of Teshigahara-Abe-Takemitsu and 1960s Japanese cinema by Jean-Baptiste De Vaulx

- A look at Japanese film music through the lens of Akira Kurosawa by James M. Doering

- The Spectral Landscape of Teshigahara, Abe, and Takemitsu by Peter Grilli

Recordings

- Air music for harp, flute, and strings (2008)

- November steps (2014)

- Orchestral works (2006)

- Takemitsu recordings on Freegal

- Takemitsu recordings on Hoopla

Takemitsu filmography

Compiled from the Japanese Movie Database and Internet Movie Database

1955 Bicycle in Dream (Ginrin; Documentary short; Gen'ichirô Higuchi & Toshio Matsumoto)

1956-07-12 Crazed Fruit (狂った果実 - Kurutta kajitsu; Kô Nakahira)

1956-08-28 Vermilion and Green (朱と緑 - Shu to midori; Noboru Nakamura)

1956-11-28 Tsuyu no atosaki (つゆのあとさき; Noboru Nakamura)

1957-06-11 When It Rains, It Pours (土砂降り - Doshaburi; Noboru Nakamura)

1958-08-31 Kamitsukareta kaoyaku (噛みつかれた顔役; Noboru Nakamura)

1959 Jose Torres (documentary short; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1959-01-09 Haru o matte hitobito (春を待つ人々; Noboru Nakamura)

1959-02-25 Itazura (いたづら; Noboru Nakamura)

1959-08-09 Kiken ryokô (危険旅行; Noboru Nakamura)

1959-10-16 Ashita e no seisô (明日への盛装; Noboru Nakamura)

1960-08-30 Dry Lake (乾いた湖 - Kawaita mizuumi; Masahiro Shinoda)

1961-03-01 Hanjo (斑女; Noboru Nakamura)

1961-03-01 Mozu (もず; Minoru Shibuya)

1961-03-29 Furyo shonen (不良少年; Susumu Hani)

1962 The Inheritance (Karami-ai; Masaki Kobayashi)

1962-01-14 Mitasareta seikatsu (充たされた生活; Susumu Hani)

1962 Love at Twenty (segment "Japan"; Shintarô Ishihara)

1962-07-01 Pitfall (おとし穴; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1962-09-16 Harakiri (切腹 - Seppuku; Masaki Kobayashi)

1962-09-30 Tears on the Lion's Mane (涙を、獅子のたて髪に - Namida o, shishi no tate kami ni; Masahiro Shinoda)

1962 Human Zoo (Ningen Dobutsuen; Short; Yôji Kuri)

1962-11-08 The Body (裸体 - Ratai; Masashige Narusawa)

1963-01-13 Koto (古都; Noboru Nakamura)

1963-02-16 Wonderful Bad Woman (素晴らしい悪女; Hideo Onchi)

1963-04-10 Shiro to kuro (白と黒; Hiromichi Horikawa)

1963-10-18 She and He (彼女と彼 - Kanojo to kare; Susumu Hani)

1963-10-27 Alone in the Pacific (太平洋ひとりぼっち - Taiheiyo hitori bocchi; Kon Ichikawa)

1964 Love (Short; Yôji Kuri)

1964 La fleur de l'âge, ou Les adolescentes (segment "Ako")

1964 The Tomb of Youth (TV Short documentary)

1964-02-15 Woman in the Dunes (砂の女 - Suna no onna; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1964-03-01 Pale Flower (乾いた花 - Kawaita hana; Masahiro Shinoda)

1964-03-28 Children Hand in Hand (手をつなぐ子ら - Te o tsunagu kora; Susumu Hani)

1964-03-29 Nijû issai no chichi (二十一歳の父; Noboru Nakamura)

1964-07-04 Assassination (暗殺 - Ansatsu; Masahiro Shinoda)

1964-07-04 Escape from Japan (日本脱出 - Nihon dasshutsu; Yoshishige Yoshida)

1964-09-19 The Call of Flesh (女体 - Jotai; Hideo Onchi)

1964-10-04 Car Thieves (自動車泥棒 - Jidôsha dorobô; Yoshinori Wada)

1965 White Morning (Shiroi asa; Short; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1965 Jose Tores (Hozee Tooresu; Documentary)

1965-01-06 Kwaidan (怪談; Masaki Kobayashi)

1965-02-28 With Beauty and Sorrow (美しさと哀しみと - Utsukushisa to kanashimi to; Masahiro Shinoda)

1965-05-16 Saigô no shinpan (最後の審判; Hiromichi Horikawa)

1965-07-03 The Song of Bwana Toshi (ブワナ・トシの歌 - Bwana Toshi no uta; Susumu Hani)

1965-07-10 Samurai Spy (異聞猿飛佐助 - Ibun Sarutobi Sasuke; Masahiro Shinoda)

1965-07-25 Illusion of Blood (四谷怪談)

1965-09-05 Beast Alley (けものみち - Kemono-michi; Eizo Sugawa)

1966-06-11 The River Kino (紀ノ川 花の巻 文緒の巻 - Ki no Kawa; Noboru Nakamura)

1966-07-02 Captive's Island (処刑の島 - Shokei no shima; Masahiro Shinoda)

1966-07-15 The Face of Another (他人の顔 - Tan'in no kao; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1966-10-01 Akogare (あこがれ; Hideo Onchi)

1967-02-25 Izu no odoriko (伊豆の踊子; Onchi, Hideo)

1967-05-27 Samurai Rebellion (上意討ち 拝領妻始末 - Jôi-uchi: Hairyô tsuma shimatsu; Masaki Kobayashi)

1967-09-30 Clouds at Sunset (あかね雲 - Akane-gumo; Masahiro Shinoda)

1967-11-18 Two in the Shadow (乱れ雲 - Midaregumo; Mikio Naruse)

1968-03-27 Two Hearts in the Rain (めぐりあい - Meguri-ai; Hideo Onchi)

1968-05-25 Nanami: The Inferno of First Love (初恋・地獄篇 - Hatsukoi: Jigoku-hen; Susumu Hani)

1968-06-01 The Man Without a Map (燃えつきた地図 - Moetsukita chizu; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1968-06-08 Hymn to a Tired Man (日本の青春 - Nihon no seishun; Masaki Kobayashi)

1968 Kyoto (京; Kon Ichikawa)

1969-05-24 Double Suicide (心中天網島 - Shinju: Ten no amijima; Masahiro Shinoda)

1969-09-10 Bullet Wound (弾痕 - Dankon; Shirô Moritani)

1970-06-27 The Man Who Put His Will on Film (東京戰争戦後秘話)

1970-10-31 Dodes'ka-den (どですかでん; Akira Kurosawa)

1971 The Centuries of the Emperors (TV Series documentary)

1971-02-26 Yomigaeru daichi (甦える大地; Noboru Nakamura)

1971-06-05 The Ceremony (儀式 - Gishiki; Nagisa Oshima)

1971-09-11 Inochi bô ni furô (いのちぼうにふろう; Masaki Kobayashi)

1971-11-03 Silence (沈黙 - Chinmoku; Masahiro Shinoda)

1972-03-25 Summer Soldiers (サマー・ソルジャー; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1972-08-05 Dear Summer Sister (夏の妹 - Natsu no imôto; Nagisa Oshima)

1973-02-24 Seigen-ki (青幻記 遠い日の母は美しく; Tôichirô Narushima)

1973-09-01 The Petrified Forest (化石の森 - Kaseki no mori; Masahiro Shinoda)

1974-03-09 Himiko (卑弥呼; Masahiro Shinoda)

1974-04-06 Shiawase (しあわせ; Hideo Onchi)

1975-05-31 Under the Blossoming Cherry Trees (桜の森の満開の下 - Sakura no mori no mankai no shita; Masahiro Shinoda)

1975-10-04 Kaseki (化石; Masaki Kobayashi)

1977-02-26 Sabita honoo (錆びた炎; Masahisa Sadanaga)

1977-11-19 Ballad of Orin (はなれ瞽女おりん - Hanare goze Orin; Masahiro Shinoda)

1978-10-28 Empire of Passion (愛の亡霊 - Ai no borei; Nagisa Oshima)

1979 Kataku (Short) Kihachiro Kawamoto

1978-12-23 Moeru aki (燃える秋; Masaki Kobayashi)

1979-12-10 Kataku (火宅 能「求塚」より - Kataku nô 'Motomezuka' yori) (Short; Kihachiro Kawamoto)

1980-01-26 Tempyo no iraka (天平の甍; Kei Kumai)

1980-11-07 Ki / Breathing (気 BREATHING) (Short; Toshio Matsumoto)

1981-02-19 Minamata no zu monogatari (水俣の図 物語; Noriaki Tsuchimoto)

1981-10-07 Rennyo and His Mother (蓮如とその母 - Rennyo to sono haha; Kihachiro Kawamoto)

1982-08-15 Yogen (予言; Susumu Hani)

1983-06-04 Tokyo Trial (東京裁判 - Tôkyô saiban) (Documentary; Masaki Kobayashi)

1983 Lanterns on Blue Waters (TV Movie)

1984 Shin yumechiyo nikki (TV Series)

1984-05-25 Antonio Gaudí (アントニー・ガウディー) (Documentary; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1985 A.K. (Documentary; Chris Marker)

1985-05-25 Fire Festival (火まつり - Himatsuri; Mitsuo Yanagimachi)

1985-06-01 Ran (乱; Akira Kurosawa)

1985-11-02 Shokutaku no nai ie (食卓のない家; Masaki Kobayashi)

1986-01-15 Gonza the Spearman (近松門左衛門 鑓の権三 - Yari no gonza; Masahiro Shinoda)

1986 In the World of Zen (TV Series documentary)

1987 Kesa no aki (TV Movie)

1987 Hiroshima to iu na no shônen (ヒロシマという名の少年; Yoshiya Sugata)

1988-05-28 Wuthering Heights (嵐が丘 - Arashi ga oka; Yoshishige Yoshida)

1989 For the Whales (TV Movie documentary)

1989-05-13 Black Rain (黒い雨 - Kuroi ame; Shohei Imamura)

1989-09-15 Rikyu (利休; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1991 The Inland Sea (Documentary; Donald Richie)

1992-04-11 Gô-hime (豪姫; Hiroshi Teshigahara)

1992 Dream Window: Reflections on the Japanese Garden (Documentary; John Junkerman)

1993 Concrete Dream (Short)

1993 Rising Sun (Philip Kaufman)

1994 Music for the Movies: Tôru Takemitsu (TV Movie documentary)

1995-02-04 Sharaku (写楽; Masahiro Shinoda)