Did you know that when Central Library opened in 1926, the entrance at 530 South Hope Street was both the "front door" and mailing address? Patrons entered the gates at Hope Street and walked up a long sloping ramp to a circulation desk at the center of the lower level. In fact, if you peer through the glass doors at street level today, you can still see the original entrance ramp.

Hope Street Tunnel Interior today. Photo Courtesy of Karina Buck

Soon after he arrived in the fall of 2012, City Librarian John Szabo casually asked, "When was the Hope Street tunnel closed?" The question bounced around amongst library staff until it was finally put to Helene Mochedlover, president of Bruckman Rare Book Friends, and Renny Day, Bruckman Rare Book Friends board member. Mochedlover and Day launched into extensive readings of eighteen years of annual reports to solve the mystery. Here's what they turned up:

In 1926, Central opened to great fanfare (see Happy 90th Birthday, Goodhue Building). In its first permanent home, Central now housed a Department of Work With Schools, a Department of Work with Children, and the prestigious Library School, then in its 34th year of existence and charging $75 tuition for Los Angeles residents and $150 for non-residents.

Children representing the years 1918-1927 display the library's circulation figure for each year

By 1928, artist Albert Herter had installed paintings of the discovery and exploration of California on the walls of the ramp leading up to the circulation desk. The Philosophy and Religion Department was established by pulling the 100's and 200's from the Reference Department and was situated to the west of the Fifth Street entrance, the current location, Meeting Room A. The report concluded with the good news that cardholders numbered 279,749 (22% of the city population.)

By 1929, construction had started on the nearby California Club and the Southern California Edison buildings. The use of the Piano Room had increased from 258 people to 370 a month. The History Department reported that the maps were very popular. The holding included 446 cataloged maps and 6,239 un-cataloged. City Hall opened, and the number of library cardholders rose to 300,951 (23% of the city's population.)

In 1930, the murals on the walls of the Hope Street Tunnel were endangered by moisture seepage, and Albert Herter was summoned to remove his works and apply them to the walls of the Reference Room (later the History Department.) Since the paintings did not fit properly, Herter was hired to extend them to fit the walls of their new home. Library cardholders now numbered 319,512 (25.8% of the city population.)

By 1931, the Great Depression was beginning to have an impact on the library. More seating was installed, and the Reference Desk reported that they fielded 80 questions per hour. The Newspaper Department could not keep up with the demand from readers. Want-ads were pulled from the papers and handed out separately.

In 1932, the circulation for self-help books increased. The administration announced that the Library School would close in June, after 41 years as a successful institution. All branches closed at 1 p.m. on Saturdays.

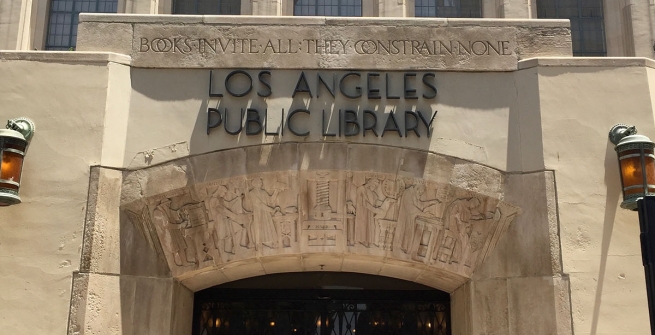

In 1935, the American Library Association stated the library, which was nationally sixth in city population at the time, was first in the number of books circulated, first in size of the area served, and second in circulation per capita. Yet departing staff was not replaced, and those remaining endured salary cuts. The annual report featured a photo of the Hope Street entrance with carvings by architectural sculptor Lee Lawrie. Hope Street was one of six entrances to the library at the time.

Receiving Desk, Central Library

Throughout the Great Depression, Central Library continued to provide checkout services in each department and maintained staff at each of the six entrances to the building. But World War II brought severe cutbacks. The 1942 Annual Report states: "The greatest dislocation has been the acceleration of staff turn-over to a veritable whirligig. The library's salary scale is so far below that of industry or even of the other city departments that clerk typists, janitors, and maintenance men have been transferred at a rate exceeding one a day to other better paid place of employment. As for the messenger clerks who do our book shelving, most of them work just long enough to absorb a week of expensive instruction and supervision and then 'softly and silently vanish away and never are heard of again.'"

By July of 1943, both the Flower Street entrance and the Hope Street ramp were closed, leaving four checkout locations instead of nine.

So, after pouring over 18 years of annual reports, detectives Mochedlover and Day had finally found the answer to John Szabo's question. The Docents are grateful for their diligent research in solving the mystery. The docents also appreciate Renny Day’s kind permission to reprint her article, originally published in the Bruckman Rare Book Friends Newsletter.

Please join us for a docent-led tour of the Central Library.

Article by Renny Day