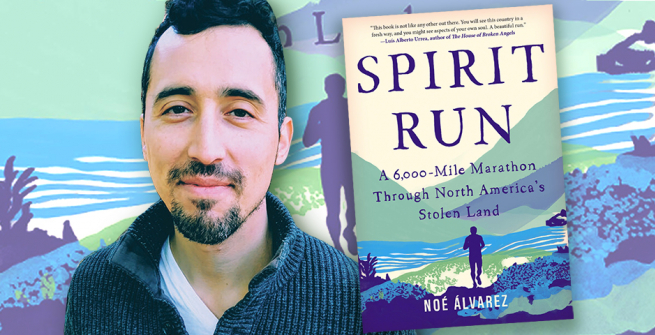

Noé Álvarez is a writer, a runner, and the son of Mexican immigrant parents descended from the Indigenous Purépecha people and raised in Yakima, Washington. He is the first-time author of the memoir, Spirit Run: A 6,000-Mile Marathon Through North America’s Stolen Land. As a disillusioned, nineteen-year-old first-generation college student, he left school, seeking deeper meaning and fellowship, to run with other Native Americans in a grueling relay run called the Peace and Dignity Journeys (PDJ). During months of running across America, anywhere from 10-30 miles a day, he learned to connect with himself, with the land and with Indigenous communities from Canada to Guatemala. In his memoir, his own memories are intertwined with the stories and struggles of his parents and the other PDJ runners, seeking healing from their painful pasts.

In Spirit Run, when you first quit college to join the PDJ Run, you confess: “I don’t understand the logic of the run" and it scared the crap out of you. Despite your fear of the unknown, what compelled you to join?

I felt like I didn’t understand a lot of things that were going on in my world but I was moving, I was being pulled in emotionally and spiritually. And what made sense to me was the spiritual aspect of the run. That they were driving at something deeper...There are things that we don’t always understand and we don’t have to... Sometimes you just know it’s the right thing to do and you just go with it. And you have to trust your soul, you just have to trust your gut that this is the right thing to do for me. Even though I have no idea of what that would look like, you know it’s a “learn as you go.” It was a very defining and transformative time for me in my life and I’m glad I did it. And I’m glad that my fear or lack of understanding of things didn’t stop me. Cause often I think that stops us. We want to know everything before we go into a situation and that’s not always possible. And that’s not always the best way to do things in life.

Can you describe the rituals of running in PDJ and the power of community?

You’d need to wake up early in the morning before sunrise and run till sunset, essentially, and then you have an opening and closing ceremony which entailed sitting with the locals, with the elders, with the children and listening to their stories. It was that part of the run that really pulled me into it.

Each day we had different reasons for running: Maybe we heard a certain story from an elder, we ran with the children, and something we thought about, a specific memory was kind of our fuel for that day...When I thought about a certain story about my mom, I was sad. Sometimes the terrain that we ran through pulls up certain emotions and I needed to get through that. So if I was going through certain emotions, if I was crying, I couldn’t just stop because I was crying...I had to keep going on. Even if my knees were hurting. And I needed to go through that for my own self. That was healing to me, as painful as it was...And when you get done...Or when you accomplish the day, you feel a sense of purpose, when you’re welcomed by the community, and they’re applauding you, you’re like, “This is what it’s about! This is the person I was hoping to reach. This is the story that I wanted to hear, and this was so worth it.”

And that’s why we are in a community of runners. You can always talk it through with some people and some elders and you can ask them for their words of encouragement and knowledge. Then you find so much healing, and you rest and you have dance and you have potluck and it’s like “that there was so much more powerful healing than running up a mountain all day.”

When you were the new guy to PDJ, you expressed some insecurity upon meeting the other members of the run, thinking, “Nothing about me says Indigenous.” What did you mean by that?

For me, I had little access to my own culture and I had little access to that information because a lot of it got lost and gets lost in migration and movement. And so a lot of us are in that stage of recuperation of restoring those many stories that got lost...As migrants and immigrants, my parents had to...They were displaced from their own homes, and along the way, they had to discard a lot of who they were and a lot of their history to survive. And whatever [my parents] passed on to me and they thought they were protecting me because they thought the less I knew of their tough past, the better. And being in Yakima, where the narrative was primarily controlled by those who were in power...You have other people’s understanding of what it meant to be working-class or Indigenous...I was internalizing someone else’s message...And I had these warped ideas.

When I went in there [and joined the PDJ team] it was kind of a surprise that I felt like I wasn’t fitting in and so I went in there trying to stay curious because there are many layers to who you are, right? There are a lot of Latino Indigenous, Canadian Indigenous, Alaskan Indigenous, Mexican Indigenous...There are so many layers to who you are and I didn’t grow up with that. And there’s a lot of separation in Yakima so a lot of the people stayed separate from their own communities.

But I was really excited about connecting with the communities and the runners and learning what it meant to be Indigenous to them. And realizing that there wasn’t an agreement! Everybody had a different interpretation. And that was the beauty of it. And that was the learning that we all had to do. There was even a different understanding of what it meant to be a runner. And I would ask questions: “What was the proper way to run? What was the proper way to do Ceremony? How to honor the communities and how to honor the feather staffs and the stories we were carrying? How should I pray?” And everyone would tell me, “You have to find your own place. Ask your questions. You have to find your own place as a runner in these communities.” And different communities had different ceremonies and they had different ways of saying “This is how you should honor our land. This is our specific story.” So if anything it made it even more complicated. [laughs] It confused me even more. And that was good! We’re very multilayered. Indigenous communities coming from L.A., from the inner cities, and from the remote villages of Mexico, and we were all coming together around the medium of running.

What was it like to grow up speaking Spanish at home and English at school?

When I was growing up, I used to get in trouble for speaking Spanish [in school]. I used to get put into detention and there’s always this fear that just because I was speaking a different language, I was saying something bad. And so I internalized that and I was very self-conscious about where I spoke Spanish, to who I spoke my Spanish.

I was thankful that my dad never let me forget it. He knew that the one thing he wanted me to do was never to forget my Spanish and so when I would go to school, all in English, and I had to go to ESL, it was so weird, it was like I was being targeted for my language. Then I’d come home and my dad would have a stack of Spanish books...and he’d have me read that and that would be my homework for afterschool. And sometimes I’d have to read that out loud to him and then write it and imitate it. So I was juggling multiple languages and I’m glad he didn’t let me forget it...When I read in Spanish, it’s so beautiful, it unlocks so many different ways of seeing the world and I love it. And for that reason, I’m like “Wow! He just described that in such a beautiful way and there’s no way I can translate that in English as beautifully.”

I didn’t know how to utilize my English as well. I used to get in trouble and try to defend myself in English but I just didn’t know how to do it and so I was a quiet kid...I guess that’s where my power of observation comes from. If I didn’t have my words, if my tongue was cut out of me, in such a way that I had to make up for that lack of ability to speak and defend myself verbally and so I relied on my vision, I relied on my observations. Being very vigilant, growing up in a tough neighborhood, I always had to watch my back, always had to watch what streets to go to, I had to watch out for trouble...details were survival. Knowing and reading as much as possible helped me survive.

How has being bilingual affected you as a writer? Do you think and write primarily in one language over the other?

I own up to the fact that I do struggle with my English still, but I think it’s a very beautiful thing where I’m at. I think because I come at things, at language, in a very fresh way it helps me to see things more beautifully. There’s still a lot of things I don’t know the names for and that’s why I describe things the way I do. Like I use metaphor and how things look a certain way.

It goes back and forth [between English and Spanish] only when I talk to my family. I talk to them in Spanish. I used to dream in Spanish and no longer. I think I handle English better these days...It’s funny though...there were times when I was writing in English, a scene when I was younger, and a scene where it was Spanish conversation. I couldn’t get deeper into that world with my English until I tried to talk through it with my mom or my dad in Spanish. When I’m in that world of Spanish, I remember different things. It was because my memory was in Spanish and to try to come at it from an English memory...it didn’t correlate. I had to unlock it [with Spanish]...different exposures unlock different memories in different ways. And so it’s a mix of both.

Spirit Run, published this year, recalls the experience of the 2004 PDJ run nearly 16 years ago and memories even further back from childhood. When did you decide to write this book? When did you come into your identity as a writer?

My entry into writing officially was through a certificate program, an evening class at a community college, way after college, around 2009 or 2010. I didn’t at all think I was a writer in college. I only feel I just recently embraced it...I was constantly going back to certain themes of immigration, homelessness, working-class...And my professor said, “look you’ve got something here. You got to do something with it.” And I think it was my passion for those stories that kept me in the game. I really want to make sense of my world. It was a memoir class I was taking. And it was a willingness to stick it through and try to make sense of my world that made me hang on as long as I did in my writing. And so now I carry it proudly. I feel like I have a responsibility to do something with these words I kept inside of me for so many years, right? I was a quiet kid. And now I’m sorta making up for the lost time and talking as much as I can.

I’m still trying to grapple with that reality [of being a writer]. I think it was a sense of confidence...It was hard...Because there was a lot of shame about who I was growing up, what it meant to be Latino, what it meant to be a farmworker, there were a lot of negative things that I internalized, and we weren’t valued as immigrants so it was hard to have confidence. The same thing with writing. It was hard to say...You know it still is [hard] to be who I am...Because I tell people I’m primarily working class. I work with homeless populations, my background’s in social work, I do a lot of shelter work and that’s what keeps me going. And I write to make sense of that. And so for me, writing is like my religion. And the only reason I am confident in my writing is because of what I do with it. It makes me accountable to my community. It makes me responsible to my people. It’s a medium for connecting and empowering my community. So for that reason, I am a very confident writer...because of what it does and what I’m trying to do with it. I’m trying to describe the lives of people who are putting in the work to make their communities better, people who are trying to heal, people who are trying to bring us love and happiness. So for me, it’s an opportunity to connect with those people, an opportunity to share those stories, to the youth who need that sort of mentorship and inspiration. It’s what I’m trying to do with the power of writing. You know? I’m not just trying to be a writer. I’m trying to be a better person through my writing.