It's a rare instance when a junior high school yearbook has implications on the social history of a city so when you see it, it’s pretty amazing; the winter 1937 edition of the John Burroughs Junior High School yearbook, Burr, is one such anomaly. This particular edition serves not only as documentation of a graduating class, it is actually a record of a thriving ethnic community that was erased in a haze of prejudice, ignorance, and fear. More than that, the yearbook shows that a handful of educators were making a concerted effort to expand children’s awareness of L.A.’s multicultural landscape during a period that is usually characterized by its antipathy in doing so. It was a gallant effort that would prove to be completely undone in just five short years.

John Burroughs Junior High School, taking its namesake from a naturalist and essayist along the lines of Henry David Thoreau, first opened its doors in 1924 with 23 teachers and approximately 400 students. The school, located in in the Mid-Wilshire area of Los Angeles, still operates as part of the Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD). Like most schools, the kids at John Burroughs Junior High School were responsible for producing a themed yearbook that would reflect on the passing of an academic year. While most yearbooks seem determined to impose contrived nostalgia or other sentimental themes, the kids at Burroughs chose to use their book as a means to celebrate the social and cultural aspects of Los Angeles. Beginning around 1933, their yearbook, Burr, began to reflect the kids’ interest in subjects such as architecture, the film industry and other topics that seemed tied to what was going on in Los Angeles at the time. Their yearbooks were brought to fruition with original artwork, as well as first-hand stories and poems that individual classes contributed. For the Winter 1937 edition, the children at John Burroughs Junior High School chose to dedicate their yearbook to the thriving Japanese community of Los Angeles.

As you know the Burr is a memory book for the Seniors which they will probably keep all their lives to recall their pleasant days here. Therefore we tried to make this one more interesting for them as well for everyone. We have more in here about them and about the whole student body, but there is also the fine theme of understanding the Japanese in America.

While it’s never stated outright how these children came to focus on this particular topic, the yearbook makes it clear that the kids had been actively exposed to Japanese culture and customs through their school. The yearbook records a meeting with a representative from the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles and individual visits to Little Tokyo for Nisei week festivities. Most remarkably, it documents a class trip to the Japanese fishing community on Terminal Island in San Pedro Bay. While Little Tokyo remains a thriving hub of culture and social interest, the residential community on Terminal Island no longer exists making this yearbook an unusual artifact documenting a lost chapter in L.A.’s storied past. Remarkably, there aren’t a lot of primary resources that were recorded while the fishing village was still a thriving community. Most of the documentation was done after the community had ceased to exist adding another layer to this unusual book.

Beginning in the late 1910s, following the demise of the Island’s resort community, Terminal Island became the home to a large, mostly working-class ethnic Japanese neighborhood that included both Japanese (Issei) and Japanese American (Nisei) residents. Most of the Terminal Islanders, as they would come to be known, were involved in the fishing industry either directly through commercial fishing or peripherally as workers in the canneries on the island. The community resided on the western end of Terminal Island surrounding Fish Harbor, sometimes referred to as East San Pedro or, by the Japanese Community, as Furusato. With an estimated population of approximately 3,000 people, the houses surrounding Fish Harbor were tightly compacted structures built by the canneries for their workforce. Because it was geographically isolated, the San Pedro ferry was usually the only way to get on the island, Terminal Island managed to develop an American culture that was reflective of a Japanese heritage but was markedly less urban than Little Tokyo, giving the Island a unique identity that existed nowhere else in the world.

![A sketch from the yearbook showing children from the school being driven to Terminal Island on what was evidently a class trip. [p.38]](/sites/default/files/media/images/blog-lapl/2019/termIlsland7.jpg)

Three of the Burroughs children wrote a feature in the yearbook that relayed their field trip to Terminal Island. The trip was intended to connect with their Nisei counterparts at the East San Pedro School as well as their Issei parents to see what daily life was like in this L.A. community that was so heavily invested in the fishing industry. What becomes clear is that the Terminal Islanders who met with the children were welcoming and eager to show the hard work that they endured day after day. Of their visit, the Burroughs kids wrote the following:

“Our main objective was not to get cold facts but to understand the people...we saw men perhaps a dozen years ago, coming over to this strange, unfriendly country with only a few dollars. We saw them working, starving, hoping, praying, sometimes in vain, finally, after long years of patience and perseverance building up one of the largest fishing ports in the world. In that moment we came to a broader understanding of the Japanese than hours of study and research had ever given us.”

![The Burroughs children’s rendering of the community. [p.51-52].](/sites/default/files/media/images/blog-lapl/2019/termIlsland12.jpg)

So how did these kids from the Mid-Wilshire region of L.A. find out about a remote fishing community off the coast of San Pedro? Again, it’s never completely spelled out in the yearbook but, it was likely an LAUSD teacher. The teachers at the East San Pedro School, where the Terminal Island children attended school, were instrumental in inviting people from the mainland, particularly LAUSD kids to the Nisei festivities and this is probably how the Burroughs kids first heard of their Terminal Island neighbors. Mildred Obarr Walizer, the principal of the East San Pedro School, was often the contact person speaking at LAUSD functions as well as social clubs, fraternal organizations, and ladies auxiliary clubs about her school and its students.

Walizer, a northern California native had come to East San Pedro to act as an “Americanization” teacher at the East San Pedro School around 1918. By most accounts, her methodology wasn’t as ‘assimilationist’ as one would expect, particularly for the period. In fact, she was proud of her school’s unique identity and she was enamored with the surrounding community. She allowed the grounds of the school to be developed in the style of a traditional Japanese garden with a red lacquer bridge which became a recognizable community landmark; she was also photographed wearing a traditional Japanese kimono on festive occasions. Walizer had a genuine affinity for the Terminal Islanders and they shared that affinity for her. She spent many of her off hours visiting families and helping them out in whatever way she could. Terminal Islander, Teruko Miyoshi Okimoto, remembered:

...she was a gray-haired motherly appearing lady and so I marveled at her unbounded energy. Being childless she adopted the entire student body as her own...Fully aware that the fathers were out to sea a great part of the time, and that the mothers were working in the canneries to augment the family coffers, she looked after the various needs of her pupils...

Mr. Otsuji Hara, President of the Japanese Association told the LA Times in 1930 that “Mrs. Walizer has been like one of us. She was more than a teacher; she came into our homes and helped us night and day with our problems.”

In many instances, Walizer acted as an ambassador of sorts between Terminal Island and the mainland. There are countless stories in South Bay newspapers recounting Walizer’s appearance at functions to discuss upcoming festivities on Terminal Island and also to invite locals to them. She also made appearances at luncheons and auxiliary meetings where she spoke to mostly caucasian audiences about Japanese culture and customs and how they had been adapted to fit in this working-class American community. While it might have been ideal to have a member of the Japanese American community speak on their own behalf, this might very well have proved impossible. The prevalent racism against minorities was, unfortunately, a rule, not an exception. Caucasian audiences at the time would have been more receptive to Walitzer, a Caucasian woman, speaking about Japanese American culture than directly from the community members that she was advocating for; it’s unfortunate, but it probably wouldn’t have happened otherwise. To her credit, Walitzer didn’t excise the community at these talks as she regularly brought the East San Pedro school children with her to demonstrate dances or tea ceremonies and illustrate cultural customs.

The Terminal Islanders trusted Walizer and welcomed her into their community. Around 1930, the community thanked her for her support by raising funds to send Walizer on a trip to Japan. When Walizer returned to the United States, she maintained her outreach by lecturing at social club luncheons and ladies auxiliary meetings but she was now armed with personal stories that included photographs and home movies of Japan. Walizer also reached out to LAUSD and professional educator meetings like those held by the Los Angeles Teacher’s Club; the November 5, 1930 meeting of the club, for instance, was held at the East San Pedro School and featured Walizer as a keynote speaker. Unbeknownst to everyone, Walizer wouldn’t be able to carry on with her advocacy very much longer.

Walizer died in 1933 after a battle with cancer and the Terminal Islanders mourned her passing. Her memorial service was held on Terminal Island inside the largest building on the Island at the time, the Fisherman’s Association. Mr. Hara, on behalf of the community, told the Los Angeles Times that “We have lost our best friend.” The school was renamed in her honor that same year.

It appears that her successor, as well as the rest of the staff, tried some degree of outreach but nowhere near the level of dedication that Walizer had. Walizer did, however, manage to expose her LAUSD colleagues to Terminal Island as a source of education and cultural diversity which trickled down to the Burroughs kids. How can we be sure? As part of the yearbook, Burr features a full page dedicated to Walizer which included a short biography that highlighted her stature among the Terminal Islanders; this was a full four years after her death leaving little doubt that she had made an impression somewhere along the line.

![Walizer’s memorial page in Burr [p. 63]](/sites/default/files/media/images/blog-lapl/2019/termIlsland23.jpg)

Inevitably, problems with outsiders attempting to convey the story of an ethnic community that was unknown to them abound. Children on the yearbook staff were not of Japanese ancestry and the language and/or phrasing used can appear either condescending or romantic, sometimes both, and it seems clear that not all of the Burroughs children fully comprehend the idea of ‘Japanese American’ —some of this is indicative of the era and some of this probably has to do with a child’s limited understanding of the world. One Burroughs student, Helen Yamamoto was Japanese American and had recently returned from Japan where she spent some time studying. Yamamoto was interviewed for the yearbook and did her best to explain some of the parallels between Japan and the United States but that task is quite a responsibility for a young girl who was probably a pre-teen at the time. Despite the problems that this yearbook has, the book is the Burroughs kids story, in their own words, of learning about L.A.’s Japanese community. It becomes more than evident that the Burroughs children were in awe of a culture and community that was, heretofore, unknown to them and the portrait that these children paint is one that is genuine, filled with both wonder and respect, and is remarkably optimistic about Los Angeles as an epicenter of multiculturalism.

Another extraordinary aspect of this yearbook is that it features a foreword by Ken Nakazawa, a writer, and professor of Japanese literature and culture at the University of Southern California (USC). Nakazawa was born in Japan and educated in the United States where he earned his Ph.D. He took a position at USC beginning in 1926 and became the first person of Japanese descent to teach at a major university in the United States. In the 1930s, he was hired by the Japanese consulate in Los Angeles to act as a spokesman on behalf of the Japanese government with the aim of building a better understanding of Japan and Japanese culture within the United States. By 1934, Nakazawa was credited with giving nearly 150 speeches to the American public as a diplomat. One of the yearbook staff, Betty Jane Reed, does report of meeting with the Japanese consulate but Nakazawa is never mentioned specifically. Interestingly, the yearbook does report that Mrs. Nakazawa visited Burroughs to teach the children Ikebana, the art of Japanese flower arrangement. Following her visit, the children were able to explain the basics of Ikebana:

“Buddhist philosophy, as an evident base to the theories of Ikebana imbues its principles of preserving natural life into the rules of flower arrangement, controlling the shapes and sizes of the vases and the chemical formulas and treatments designed to prolong the life of the flowers…”

This particular yearbook stands as a paean to a once-thriving community that was unique in the cultural landscape of Los Angeles. It is evidence that Los Angeles was beginning to acknowledge its Japanese heritage, a recognition that was slow but inevitable. It was a realization that was bolstered by compassionate educators invested in expanding minds about cultural diversity in our great city; moreover, it reminds us of the importance of great teachers in our lives. Unfortunately, all of this would be thwarted by a single event: the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. By February 1942, executive order 9066 was issued by Franklin D. Roosevelt leading to the internment of the ethnic Japanese population across the country. Terminal Island was hit particularly hard by 9066 when all residents on the island were given 48 hours to vacate their homes. They would never be able to return. The Mildred Walizer School and the entirety of the fishing village were razed during the Navy’s takeover of the Island during the war. Thereafter, Burr would start to shy away from the cultural curiosity that was flourishing in the 1937 edition of the yearbook

A copy of the Winter 1937 edition of Burr is available for research as part of our Special Collections holdings.

A big thank you to Angel City Press and authors Naomi Hirahara and Geraldine Knatz for their magnificent book, Terminal Island: Lost Communities of Los Angeles Harbor that spurred my interest in all things Terminal Island.

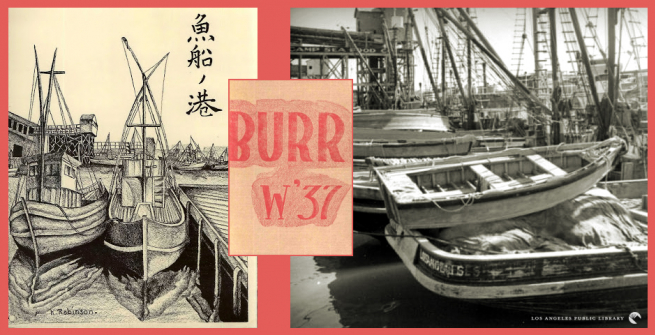

![(L) Boats docked by repair shop on Terminal Island, [ca. 1938]. Herman J. Schultheis Collection. Los Angeles Public Library. (R) Drawing of fishing boats by Burroughs student, Keith Robinson. Robinson’s drawings in particular show remarkable skill and talent. [p.89]](/sites/default/files/media/images/blog-lapl/2019/termIlsland16.jpg)