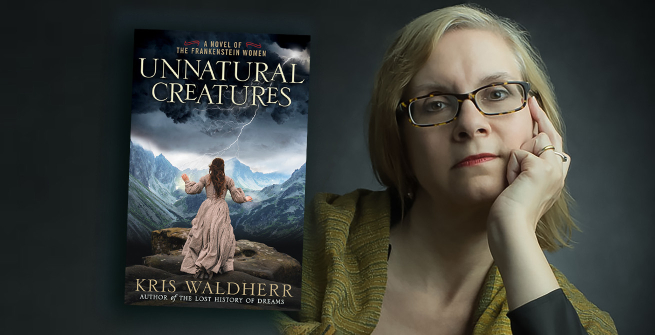

Kris Waldherr's many books include The Book of Goddesses, Bad Princess, and Doomed Queens. Her debut novel The Lost History of Dreams received a starred Kirkus review and was named a CrimeReads best book of the year. She is also the creator of the Goddess Tarot, which has over a quarter of a million copies in print. She lives and works in Brooklyn. Her latest novel is Unnatural Creatures: A Novel of the Frankenstein Women and she recently talked about it with Daryl Maxwell for the LAPL Blog.

What was your inspiration for Unnatural Creatures?

Frankenstein is one of my very favorite books. As much as I love it, I’ve often wondered about the three women surrounding Victor Frankenstein: his mother Caroline, bride-to-be Elizabeth Lavenza, and servant Justine Moritz. What were their stories? And so Unnatural Creatures came into being as a reworking of Frankenstein told exclusively from the female point of view.

How did the novel evolve and change as you wrote and revised it? Are there any characters or scenes that were lost in the process that you wish had made it to the published version?

From the beginning, I set up very clear rules for Unnatural Creatures. The first was that it had to be written as a parallel story to Frankenstein: everything that happened had to work within Shelley’s timeline in the novel, or takes place during periods that are “off stage” from Victor’s first-person narrative or subject to his unreliable perspective. My second rule was that all of the scenes had to be written from the female point of view.

For the most part, I managed to adhere to these rules, though a few exceptions were made. For example, I ended up incorporating the point of view of Henry Clerval, Victor’s best friend, in two scenes; readers will understand why when they read them.

In terms of lost characters, originally there was another maid in the Frankenstein household who had her own subplot. However, with three protagonists already in play, the maid’s subplot unnecessarily complicated an already rich stew. It was hard to pare her back—she was a lot of fun to write—but the book is definitely stronger for the loss.

How familiar were you with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein prior to writing Unnatural Creatures? Did you have to do a bit of research beyond looking at the original novel? If so, how long did it take you to do the necessary research and then write Unnatural Creatures?

I was extremely familiar. I first read Frankenstein as a child of twelve and have reread it since then every few years. Before I set down a single word of Unnatural Creatures, I spent many months reading as much as I could about Mary Shelley and her circle, as well as reading theories and interpretations of Frankenstein and the science and history of the late 18th century. I traveled to Geneva and the surrounding areas where Frankenstein takes place. I also reread all editions of Frankenstein again, some several times. As for the drafting of the book itself, that came in starts and stops. I was promoting my first novel The Lost History of Dreams at the time, so there were a lot of interruptions. From start to finish, Unnatural Creatures took about three years to research and write, which is average for me—I’m not a fast writer. It was fortunate timing that I began researching in 2018, which was the 200th anniversary of the publication of Frankenstein. This led to an abundance of Frankenstein-themed conferences and publications, which made me a very happy author.

What was the most interesting or surprising thing that you learned about Mary Shelley and/or the novel during your research?

What surprised me most were the historical aspects of Frankenstein, which I think often get overlooked. Most readers of Frankenstein tend up focusing on the scientific and philosophical aspects, of which there are many.

Though Mary Shelley began writing Frankenstein in 1816, it’s generally accepted that the novel takes place toward the end of the 18th century, which was a time of great scientific and political upheaval. During my readings of Frankenstein, I’ve always been struck by the plot point of Justine’s aunt in Chêne, who serves as the maid’s alibi when she’s accused of a heinous crime. Why does Justine mention Chêne, a small village south of Geneva, so specifically? When I learned Chêne had been forced under French rule in 1792, I experienced a “Eureka!” moment that led me to wonder how the French Revolution may have affected Shelley’s narrative.

With this, I began to read everything I could find about Geneva during this era. To my surprise, I learned Geneva had experienced several revolutions of its own, and in 1794 executed eleven syndics—judges who served as Geneva’s ruling aristocracy—in Plainpalais, the same place where Victor’s creature commits his first murder. (In Frankenstein, Victor’s father is identified as a syndic.) Mary Shelley’s travel narrative History of a Six Weeks’ Tour, which was published the year before Frankenstein’s 1818 first publication, specifically mentions the execution of the syndics in Plainpalais. If it’s a coincidence, it’s an interesting one!

Were you intimidated by the idea of writing a new work and re-interpreting the characters of a novel as well known as Frankenstein?

It was incredibly intimidating to take on such a beloved novel. To be honest, I think I might not have dared attempt Unnatural Creatures without the encouragement of my literary agent, who believed I could write it. The hardest part was getting up the courage to dive in. I tried my best to be as respectful as possible to Shelley’s novel—Unnatural Creatures is meant as a loving tribute to it.

Do you have a favorite Frankenstein pastiche, television or motion picture adaptation/interpretation? A least favorite? (I realize that you may not want to address this one, and if that is the case, please don’t. But I also realize it might be so bad that it could be fun to answer.)

When I was a child, there was a television mini-series called Frankenstein: The True Story. Reader, it was so not the true story, but I adored it. The mini-series starred Michael Sarrazan as the creature, who is initially handsome but begins to rot when Victor’s process proves impermanent, and Jane Seymour as Prima, the creature’s bride. (I think she was supposed to be his bride; it may have been that Prima was just a new-and-improved creation.) I liked that the creature was good at heart though he was ugly, and Prima was evil though she was beautiful. I recall a scene where the creature is brought to the opera by Victor in an attempt to educate him and another where Prima is decapitated by the creature during a ball scene. Everything comes to an over-the-top end in the Arctic.

In terms of favorites, I really liked the Kenneth Branaugh film of Frankenstein, though its rather gory, which might be hard for some to take. It comes closest to how I envision Victor’s creation of his monster and it includes the frame device of Arctic exploration. And of course, there’s always Mel Brooks’ Young Frankenstein, which is a delight.

Do you have an idea or theory regarding why/how Frankenstein has continues to be so culturally significant after two centuries?

I think Frankenstein is one of those novels that speak to readers on multiple levels. Besides being a suspenseful page turner, it’s a deeply philosophical book—it’s hard to believe it was written by a teenager! You can read Frankenstein as a parable about the dangers of personal hubris, a cautionary tale warning us not to play God with science, or as a Shakespearean tragedy recounting the fall of a noble family. Finally, Frankenstein is a heartbreaking account of parental abandonment. Think of how differently the story would have been had Victor been a good “father” to his creation!

Another key to Frankenstein’s popularity: both Victor Frankenstein and his monster are deeply compelling, eloquent characters. Both have become entrenched in our cultural psyche as mythic archetypes—the mad scientist and his monster—though it’s funny that some people don’t know that the name Frankenstein refers to the scientist, not the monster. The monster remains nameless in the novel. (Spoiler alert: I do give him a name in Unnatural Creatures.) Nor do they realize Victor isn’t a doctor; he’s a precocious grad student run amok. To quote my author friend Alyssa Palombo, “Victor Frankenstein is the ultimate tech bro.”

What’s currently on your nightstand?

These days, a lot of fiction. I’m excited to dig into Emma Donoghue’s new novel Haven and Margaret Porter’s The Myrtle Wand, which is about the ballet Giselle. I recently finish an advance copy of Molly Greeley’s Marvelous, a very moving historical retelling of Beauty and the Beast. It’s simply spectacular, and I think it’s going to make a splash when it comes out next year. Finally, I’m halfway through I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith. I’m amazed it’s taken me so long to read it—it’s laugh-out-loud hilarious.

Can you name your top five favorite or most influential authors?

Yikes, that’s hard! As a child, I would have said Louisa May Alcott, because I wanted to be Jo March when I grew up, and Carolyn Keene due to my obsession with Nancy Drew. I was also hugely influenced by the Brontes and Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, of course. Now that I’m an adult, I never miss anything by Diane Setterfield and Sarah Waters.

What is the last piece of art (music, movies, tv, more traditional art forms) that you've experienced or that has impacted you?

When I was in London this summer, I saw a wonderful exhibition about the life of Beatrix Potter at the V&A Museum. I was very moved to learn of her conservation efforts in the Lake District, and how she used her wealth from her Peter Rabbit books to transform the world around her. Closer to home, my daughter and I are obsessed with the Broadway musical Hadestown. It interweaves the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice with the story of Persephone and Hades. I’ve created books about both myths—a picture book entitled Persephone and the Pomegranate and the novel The Lost History of Dreams—so the stories are very close to my heart. We’re excited to see Hadestown again now that Lillias White is playing Hermes, an ingenious piece of cross-casting.

What is the question that you’re always hoping you’ll be asked, but never have been? What is your answer?

Hmmm, that’s a good question! I’m never asked about dealing with writer’s block, though I teach about it in writing workshops. In my experience, writer’s block usually comes down to three reasons. The first is we don’t yet know enough about what we’re writing; if that’s the case, take a step back and do what still needs to be done, whether that be thinking, research, or whatever else is part of your pre-writing process. The second is perfectionism, which is really a form of fear. Finally, sometimes the words aren’t flowing because we’re just plain tired. Take a break and trust the muses will return when you’re ready.

What are you working on now?

I always have a number of projects underway, but the main one these days is a new novel. It’s too early to share much, but I just returned from a writing retreat where I made good progress. Though it has gothic elements, it’s more of a swoony romantic saga set in 19th-century Venice and Russia. After some time circling about this new novel, I’m finally past much of the research and drafting in earnest.