Ideally situated in the Baldwin Hills with panoramic views of downtown Los Angeles and the San Gabriel Mountains, View Park boasts a distinctive mix of Spanish, colonial, Tudor, and ranch-style homes on palm-lined streets with mild temperatures typically ten degrees cooler than those in the rest of the Los Angeles basin.

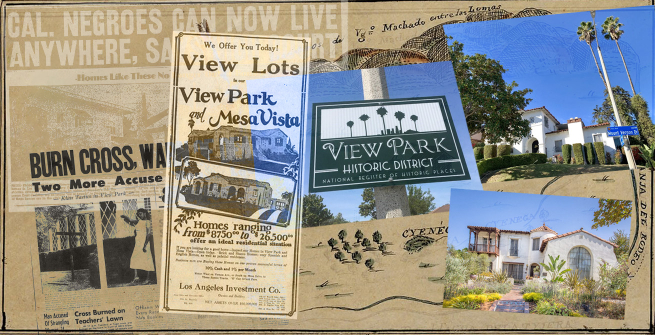

But the idyllic setting of View Park belies an ugly history of racially restrictive and discriminatory housing practices. View Park was developed by the Los Angeles Investment Company (LAIC) exclusively for white homeowners. LAIC placed restrictive housing covenants into the property deeds that excluded minorities from occupying property in the area unless they were domestic servants. This was not an unusual practice at the time. In 1940, eighty percent of Los Angeles property was off-limits to African Americans.

Clause XVI Limitation of Ownership:

No persons, except persons of the Caucasian race, shall be allowed to use or occupy said property, or any part thereof, except in the capacity of domestic servants of the occupant thereof.

View Park sits on land that was once part of the Rancho La Cienega o Paso de la Tijera. Governor Manuel Micheltorena awarded the Mexican land grant for Rancho La Cienega to Vicente Sanchez in 1843.

In 1846, Vicente's grandson, Tomas Avila Sanchez, inherited the land.

Tomas Sanchez became the first Mexican American sheriff of Los Angeles in 1860. Sanchez never lived at Rancho La Cienega, and in 1875, he sold the property to Francis Pliny Fisk Temple of Temple & Workman Bank. The bank's ownership of the land was short-lived. Shrewd businessman E.J. "Lucky" Baldwin cashed in on the bank's unsound business practices and a statewide financial panic to take possession of Rancho La Cienega and other Temple & Workman real estate holdings.

Baldwin used the ranch primarily for dairy farming. After his death in 1909, his daughters Clara Baldwin Stocker and Anita Baldwin McClaughry inherited millions of dollars in real estate, including Rancho La Cienega.

The Los Angeles Investment Company was formed at the turn of the century by members of the Orpheum Theatre orchestra as a cooperative building company to purchase land and finance and build homes. In 1913, the original directors were indicted for "over speculation and fraud," but LAIC was considered "too big to fail," and the Supreme Court ruled that it could continue under new management that included L.A. Times publisher Harry Chandler and real estate lawyer Henry O'Melveny, among others.

The first board of directors had entered into a contract with the two Baldwin sisters to purchase two tracts of land in the Baldwin Hills. The larger tract was just over 3,000 acres, and the smaller parcel was 500 acres. LAIC was able to start building on the smaller tract in the 1920s, but it took another decade of contentious negotiations with Clara Baldwin Stocker and Anita Baldwin McClaughry to acquire the largest tract and start developing View Park Intoto.

View Park was designed for white professionals and their families. The houses had large front yards, and many had servants' quarters and swimming pools.

Before View Park was fully developed, it was the site of the first Olympic Village, built to house all the athletes of the 1932 Olympic Games in one location. The Baldwin Hills site was selected over four others under consideration. It offered a centralized location, only 25 minutes from downtown L.A. and 10 minutes from the Coliseum. However, the decision was based not on location but on climate. Thermometers were placed in all the potential sites, and Baldwin Hills was consistently ten degrees cooler than the others.

Designed by H.O Davis, the 550-cottage Olympic Village was built in just two months for $500,000. Twenty-five thousand geraniums, eight hundred six-foot palms, and seven acres of new grass transformed the barren hills into lush parkland.

The village included five dining halls (each team was invited to bring its own chef), a post office, a radio station, a hospital, a fire station, and a movie theater.

It must be noted that only male athletes were housed here. Female Olympians were housed at the Chapman Park Hotel on Wilshire Boulevard.

The dismantling of the village began immediately after the conclusion of the games. The cottages were sold for $140 ($210 if furnished). Many were shipped to far-off places like Copenhagen, Japan, Berlin, and Hawaii. The only remaining traces of the village are the street names Olympiad Drive and Athenian Way.

The Olympic Village was a smashing success and set a precedent for future Olympics. The concept of thousands of athletes of different backgrounds, beliefs, and languages living together in one shared community has become a mainstay of the Olympic experience.

In the 1948 Shelley v. Kraemer case, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive housing covenants were unconstitutional and could not be legally enforced. The ruling did not put an immediate stop to discriminatory practices as realtors and lenders employed other tactics to keep out minorities and maintain ViewPark's "homogenous" population.

The first Blacks who moved into View Park in the 1950s faced intimidation, hostility, vandalism, and cross-burnings, but they began breaking down barriers and integrating the community.

As more African Americans moved into the neighborhood in the early 1960s, white residents began moving out, a pattern known as "white flight." After the Watts Riots in 1965, the white exodus gained momentum. By 1970, View Park was 75 % African American.

The same features that attracted white professionals in the thirties and forties attracted black professionals, athletes, and entertainers to View Park, which became known as the "Black Beverly Hills" Ray Charles, Ike and Tina Turner, Michael Cooper, Regina King, and Issa Rae are among the many black celebrities who have called View Park home.

In 2012, in response to several new commercial developments in surrounding communities, View Park residents began exploring ways to preserve the distinctive character of their unique neighborhood. Two residents, Andre Gaines and Ben Kahle, co-founded the non-profit View Park Conservancy in 2013.

Ineligible to become a Los Angeles City Historic Preservation Overlay Zone because View Park lies in unincorporated Los Angeles County, the group focused on applying for a national-level designation on the National Register of Historic Places. The View Park Conservancy hosted numerous meetings to raise awareness of the neighborhood's historical significance and to build support for the costly and complex process of seeking the historic designation. The grassroots organization raised over $100,000 for the cause. View Park was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on July 12, 2016.

View Park was deemed significant for its African American ethnic heritage and its architectural integrity. View Park is the largest historic district in the United States, so designated because of its association with African American history.

"View Park's inclusion into the National Register of Historic Places underscores its historic, social, cultural, and architectural significance locally and across the country. This designation helps preserve the community's worthy legacy while charting its path forward." —Los Angeles" County Supervisor Mark Ridley Thomas