This post is the sixth in a series of excerpts serializing the book Feels Like Home.

Chapter 2

From Belle to Burden and Back Again - part 2 by James Sherman, Librarian, Literature & Fiction Department

In 1974 the City Council, after investigating twenty-three possible sites for a new library, hired Charles Luckman Associates to do a feasibility study. Luckman and City Administrative Officer C. Erwin Piper had a special relationship—in choosing a contract for a Central Library feasibility study and site selection in 1974, thirteen applicants were narrowed down to three, and after interviews were conducted, Piper ignored all recommendations and awarded Charles Luckman Associates the consulting contract to offer up sites for a new Central Library after “Piper had declared himself to be the only person with the power to decide”.

In 1976 Luckman presented his report to the City Council, narrowing down the sites to three locations—the library’s present site; Bunker Hill (where juror parking currently is), which was preferred by the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA); and a site east of Pershing Square that would extend through to Broadway, which was Piper’s preference. It’s perhaps, therefore, no coincidence that Luckman chose the Pershing Square site. While this choice would cost $83 million (and his company would receive $2.3 million to build it), Luckman claimed that restoring and expanding the old Central Library building would be impractical and prohibitively expensive, at between 35 to 38 million dollars. He stated that it was impossible to “remodel the present building or add to it,” summing up that it was “a lousy library.” (One can’t be too hard on Luckman because Library Administration and Commissioners were essentially saying the same thing, wedded as they were to the idea of a massive new building—and many librarians who worked in the overtaxed building felt the same way.) In addition, there was a discussion of selling the Central Library site as part of a plan to fund the new project; this had been the dream of prior Mayor Sam Yorty. The proposals for both the Pershing Square site and the Bunker Hill site assumed the sale of the Central Library site to developers.

The Pershing Square/Broadway project was sunk by its enormous cost, the lack of support from the CRA, and organized protests by Broadway merchants.

In December 1976 the City Council led by Zev Yaroslavsky voted to instruct Piper to issue an RFP on a study of library rehabilitation and expansion. But Piper was a skillful bureaucrat in the service of his friend, and the RFP was never issued. Luckman wrote a letter offering to produce the study under his existing contract at no cost, and Piper sent the letter to the president of the council, John Gibson. Instead of putting Luckman’s proposal in front of the whole council, Gibson sent it directly to the Recreation Committee, where Piper fans and Council Members Lindsay and Lorenzen, who had been supporters of the Pershing Square plan, voted to accept Luckman’s generous offer and thereby skirted the City Council's request. (According to journalist John Pastier, Lorenzen was the recipient of the largest amount of political contributions by Luckman Associates.)

Because the new study focused on Central Library’s rehabilitation and expansion, the second Luckman report directly refuted the first. To explain his change of heart, Luckman partner Sam Burnett stated that “we made the negative comments before we studied the old building…When we studied it in detail, we found it was possible to renovate if done properly.” And apparently it could be done much more cheaply, by at least ten million dollars. Despite his sudden interest in Central Library, Luckman was still no preservationist: He stated that renovation of the old central section would involve a complete gutting—“ It must be clearly understood that we are not talking about remodeling the building…you can’t do it.”

This monster was to be paid from CRA funds, based on tax receipts. These funds evaporated with the passage of Proposition 13. Piper, approaching retirement, struggled to find funds for Luckman, and the project limped along. Somehow the Luckman study was becoming the plan for renovation—it was chosen among other applicants who had been given insufficient time and notice to prepare proposals. Luckman not only had the advantage of three years’ experience and the support of Piper, but in one case, he was allowed to comment on the proposals of other applicants. Beyond the inappropriate schemes to force Luckman’s plan to become a reality, the images of the plan—most shockingly, those that show the Rotunda violated with escalators—helped awaken many people to the problem that preservationists had been addressing all along.

In response, the Southern California chapter of the AIA took the extraordinary step of filing a lawsuit, on January 11, 1979, to stay operation of the Central Library expansion and renovation and to set aside an invalid EIR to stop Luckman’s “study” from becoming “the plan.” The oft-ignored preservationists, cut out of the process for over a decade, had found their voice and their teeth.

Between the Green Report and the all-consuming political maneuverings, preservation efforts had been ignored in the quest for a large modern library. The Cultural Heritage Board designation of the library as a landmark in March of 1967 changed nothing, a 1968 AIA report for preservation of the library was ignored, a lawsuit to stop the destruction of the West Lawn garden for a parking lot in 1969 was unsuccessful, and the Central Library’s listing on the National Register of Historic Places in 1970 (which was only the second listing in L.A.’s history), seemed to have little sway when it came to plans to destroy the Goodhue Building.

Certainly, in newspaper news coverage at the time, there is a primary focus on the byzantine twists and turns of politics. On closer scrutiny, however, there were voices of praise for the existing building, from a Ray Bradbury letter to the editor (“The old library looks like Tomorrow itself...Outside of the Music Center, it is the only building downtown worth looking at”), to more regular columns by architecture critics, most remarkably the sustained, clarion calls regarding the importance of Central Library penned by Joseph Giovannini of the Herald Examiner.

The AIA lawsuit was unprecedented and demonstrated the growing power and organization of the preservation movement. As motivated as they may have been on aesthetic grounds, the AIA and their lawyers wisely went after the muddled process of city decision making. Apparently the City Council’s certification of the EIR was not an approval of a project or alternative, yet somehow a notice of determination was produced by City officials that stated inaccurately that in fact, the Council had approved the project itself. The lawsuit was concurrent with the ire of City Council regarding the fact that the choice of Luckman and his design by the Board of Public Works was made under questionable circumstances and was thus highly problematic: Yaroslavsky informed Mayor Bradley of the complaints with the process, not in the least that other firms were given only one day for interviews. The City Council voted successfully to put the final kibosh on the Luckman plan.

But the beleaguered Central Library building was not yet out of harm’s way.

James Sherman is a reference librarian in the Literature & Fiction Department at Central Library. He has worked as a young adult librarian, a community college reference & instructional librarian, and a cataloger & electronic resources librarian at a law firm. He has an M.F.A from UCLA's School of Theater, Film and Television and has worked for the Sundance Institute as well as in development and physical production. James also worked as a grant writer for arts organizations and as a consultant researcher for the NYC Board of Education and the United Nations Development Programme.

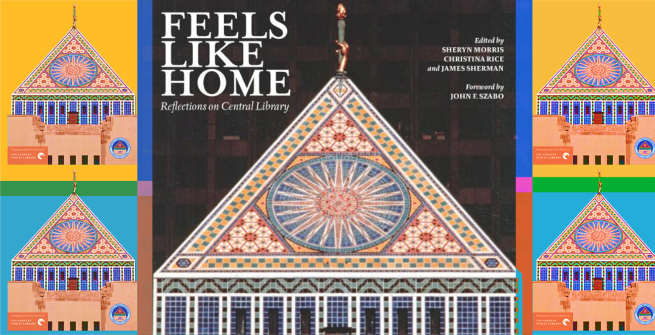

Feels Like Home: Reflections on Central Library: Photographs From the Collection of Los Angeles Public Library (2018) is a tribute to Central Library and follows the history from its origins as a mere idea to its phoenix-like reopening in 1993. Published by Photo Friends of the Los Angeles Public Library, it features both researched historical accounts and first-person remembrances. The book was edited by Christina Rice, Senior Librarian of the LAPL Photo Collection, and Literature Librarians Sheryn Morris and James Sherman.The book can be purchased through the Library Foundation of Los Angeles Bookstore.