This post is the third in a series of excerpts serializing the book Feels Like Home.

Chapter 1

"A Wanderer and Homeless Waif": Los Angeles’ Central Library - part 3 by Glenna Dunning, Former Librarian, History & Genealogy Department

On July 1, 1891, the library abolished its system of user subscription fees and was therefore made entirely free, "deriving its sole support from the annual appropriation of a portion of the city funds, and from voluntary donations.” The number of new patrons became a flood and, in 1893, the Board again addressed the desperate need for larger quarters.

"The demands upon the library by the public have increased in astonishing ratio, the Board has not been able, on account of the limited space allotted for the use of the library...to give that amount of satisfaction in the service which the public has a right to demand. Our crying necessity is for more room and better accommodations. It is a fact demanding recognition that the public requires better service than it is possible to render in the present cramped quarters...If the library could be afforded sufficient space so that the books could be arranged in a way that would give convenient access to the shelves, the result would be the greatest accommodation to the public...If an arrangement could be made by which the library could have more room in the City Hall, or be removed to a location where better accommodations could be secured, it would be of the greatest service to the public."

By 1895 the library had 42,000 volumes, a circulation of 329,000 volumes, and more than 20,000 readers. Finally, in 1897, the City Council agreed to adopt the Board's 1891 recommendation to establish "delivery stations in at least four of the outlying parts of the city, [thus reducing] the pressure upon the central library so much that it would be a great deal easier to handle the large crowds that come to the library daily." Later that year, the Castelar reading room was opened in the oldest and most crowded part of the city, near the Plaza; this was followed by the Macy Street reading room in May 1898.

At the same time, the Central Library was still renting space in City Hall. Some improvements in the facility had been made and the Library Board noted, in its 1896 annual report, that "the installation of electric lighting into all the [City Hall] rooms devoted to the library use has contributed largely to the comfort of the patrons and the convenience of employees, the degree of illumination being very satisfactory."

Still, not everything at City Hall worked so well. On January 16, 1896 "the elevator in the City Hall came to a full stop and throughout the afternoon the throngs of library patrons were forced to use the stairs to reach the public library...The City Clerk, the day before, had informed the City Council that such an event would occur if he was not granted permission to purchase oil for fuel to keep the steam plant at the Hall in operation." In May, strange smells began to filter into the library. The plumbing system was suspect and, on May 8, 1896, the Los Angeles Times disclosed that "the various closets, sinks and drains et al., in the City Hall [have emitted and] will continue to emit their noisome odors for some time, as the Sewer Committee has decided that it will cost entirely too much money to even partially repair the plumbing apparatus in the building...the Health Officer assured the City Fathers that to force the public library girls to put up with the accommodations, or lack of accommodations was simply cruelty to children."

Then, in October 1896, the electrical lights which had been publicized earlier joined the growing list of City Hall problems. George Stewart, chairman of the Library's Finance Committee, informed the City Council that, "On several occasions lately the electric lights provided in the rooms of the public library have been shut off for reasons unknown to the [Library] Board, early in the evening; and in the absence of gas, has compelled the non-use of the rooms by the public, and has amounted to quite a serious inconvenience and detriment.”

Another situation that should have been added to the list of problems was the library's increasingly crowded conditions, an ongoing dilemma which the December 25, 1896, Los Angeles Times reported "undoubtedly keep away a most desirable clientage, and one from which the library might have much to expect for its future growth...It is hoped that...a library building with appliances worthy the name may at an early day decorate our city." No active steps were taken in that direction and, by 1900, it was again reported that "books were overflowing the crowded rooms of the City Hall [Library]. They extended to the attic and basement and were even lodged on the stairs. There was a grave question of the safety of the floors under the weight of books. Documents were removed to the basement where these rooms were declared unsanitary for the lack of air, and the newspapers had to be housed in another building provided by the Chamber of Commerce...The Library Board estimated that 50,000 square feet of floor space was needed for present library activities, while the City Hall quarters provided only 14,000 square feet."

Mary Jones, Librarian at the time, was committed to relieving the over-crowded conditions of the library and "arousing the interest of citizens in a Central Library building." In 1904 she proposed that a new library be constructed in Central Park (now Pershing Square); a special election was held and voters approved the construction. The legality of this special election was contested by the City Council and the issue was fought in court, but John Wesley Trueworthy, president of the Library Board, stated: "It is expected that a decision will be handed down by the Supreme Court in April on the right of the city to place a library building in Central Park, in accordance with a vote of the people." He added "I am confident that, if we can secure the park for a library site, we can yet secure the gift of $350,000 for the erection of the building. The city could not buy a library site equal to Central Park for less than $2,000,000...We simply would add a beautiful building to the attractiveness of the park." The election and its results were upheld by Supreme Court decision in 1906, but plans to use the Central Park site were not given any serious consideration by civic authorities due, in part, to "heavy bond issues for various local improvements and for the great enterprise of the Owens River aqueduct which have so far prevented the initiation of a specific campaign for a library building." The library was forced to remain, as one reporter remarked, "still a wanderer and a homeless waif."

For the foreseeable future, at least, the Los Angeles Library would have no home of its own. Continuing to rent overcrowded quarters in City Hall was no longer a viable option, so the Board of Directors began a search for a new location. On January 11, 1906, the Los Angeles Times reported that "The directors of the public library advertised for bids for temporary quarters for the library, and last night opened the bids received. Homer Laughlin offered the Board the two upper floors of the Laughlin Annex block, for a monthly rental of $850 for the first three years and $1000 a month for two additional years, should the space be required for five years." Surprisingly, although a majority of Board members favored accepting the Laughlin building, "some members of the Board feel that it may be wise to retain these quarters [in City Hall] for the present" but they were outvoted.

On March 30, 1906, the library completed its move to the Laughlin Annex, a fire-proof business building at Third and Hill streets (next to Grand Central Market). The library occupied four rooms on the upper floor and had storage facilities in the basement for a total of 20,000 square feet; there was also a 5000 square foot roof-garden reading area consisting of "flowering hedges and fruit trees, and a section where men might smoke while they read." Incredibly, within only two years the library's facilities were crowded to capacity. It was reported that "there is no room for expansion in the present quarters. It is reasonable to suppose that the use of the library will keep on increasing...[needed book] stacks could not be put in the present quarters without spoiling the reading-rooms, which are already so crowded by patrons that if more books went in, a proportionate number of patrons would have to go out." "It will be, under the most favorable circumstances, some years before a public library building owned by the city can be expected...During these years of waiting for its own library building, the library cannot afford to stop growing...Unless some change was made, there would soon be no place to put new books, nor to seat new patrons.”

Again, the Library Board found itself in the position of having to search for a new location. They moved quickly and, by the end of 1908, they closed a deal with the Hamburger Realty Company for space in a new building being constructed at Broadway, Eighth and Hill streets. This building was to be Hamburger's Department Store and the library would occupy a large portion of the third floor. It seems like an odd choice but the building was enormous and was, for many years the largest department store west of Chicago. It was "not only fireproof, but heated and ventilated throughout by a modem blast-air system, both hot and cold, which will change the air every thirty minutes, and at the same time enable patrons of the library to inhale pure air at a constant temperature of 70 degrees." The site was also located in the burgeoning business district, and "every street-car line either passes the Hamburger building or transfers thereto, the building being almost in the exact center of the population of the city."

The library was located on the third floor with access provided "by eight express elevators and an escalator, or moving stairway, which in itself is capable of accommodating about 4000 people an hour." The library occupied 31,000 square feet in the reading rooms, possessed about 10,000 square feet for storage and binding purposes and approximately 28,000 square feet in the roof garden reading area, making a total of almost 70,000 square feet, compared with 25,000 square feet at the Laughlin building.

The terms of the five-year lease were certainly beneficial to Hamburger Realty, as the library was required to pay rent of $18,000 per year. It was later charged that Charles Lummis, the librarian, was "business-like but not a businessman and the iron-clad lease he signed at an inflated rate was more detrimental to the library's future than the roof garden was advantageous. The move to the Hamburger Building left the library financially disadvantaged for some years to come."

The exterior architecture and decoration of the Hamburger Department Store was certainly beautiful but, for such a large building, the interior space was surprisingly cramped and ill-suited to the smooth movement of people and materials. The numerous large columns on each floor dictated the placement of furniture and, to an extent, the pattern of the workflow. Oddly, one of the most nagging concerns for the library administration was the fear that the public was starting to regard the library as part of the department store and, in fact, the use of the collection was decreasing during the first few years at the Hamburger location. The Library Board, in its 1910 Annual Report, observed that "as long as the library continues to remain [at Hamburgers], it will not accomplish all the good it should. Situated as it is on the third floor of a large department store building, it appears to the ordinary passerby that, because of its unavoidable setting, it is a part of the department store itself...Many of its former patrons are no longer using the Main Library, owing to the inconvenience of its location. The best proof of this lies in the falling off of the circulation of the Main Library, notwithstanding the phenomenal growth of Los Angeles."

Having discussed several possible solutions, the Board realized that, once again, the library needed its own building or at least a location which would be "library friendly." The option of moving to a site in Central Park was re-examined and the Library Board concluded "that the ideal site for a new Library Building is Central Park, preferably the Olive Street frontage, midway between Fifth and Sixth Streets. Such an arrangement would in no wise interfere with the beauty of the park and would do much in the direction of popularizing this institution." However, the library was locked in by its five-year lease and had to remain at Hamburgers for the immediate future.

Not everything was bleak, however. In 1910 the library received a gift of $210,000 from Andrew Carnegie, "to be used in the erection and equipment of six branch library buildings." The Board acknowledged the gift in its 1911 Annual Report and offered the hope that Carnegie's gift would inspire the public, thus "arousing civic pride to a degree that will provide a handsome Main Library Building, comparing favorably with the buildings of Denver, Seattle, and eastern cities of less size and importance than Los Angeles, 'a consummation devoutly to be wished."' Around the same time, Mrs. Ida Hancock Ross, the widow of oilman G. Alan Hancock, bestowed, in her will, a gift of $10,000 for a memorial room in the new library, "providing it is built within five years."

Glenna Dunning (1947-2015)

In the History & Genealogy Department at Central Library, Glenna Dunning was the go-to librarian with questions relating to really early Los Angeles history and was able to keep all those adobes and ranchos straight. If some aspect of Los Angeles history piqued her interest, it wasn’t long before an article she penned on the subject showed up in the Los Angeles City Historical Society Newsletter. Glenna’s many historical writings are cited in the library’s California Index and serve as a tangible reminder of the dedicated librarian who served her beloved city well. A fully cited version of “A Wanderer & Homeless Waif” is available on request.

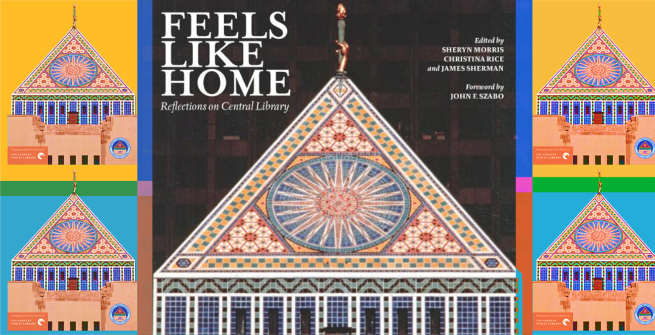

Feels Like Home: Reflections on Central Library: Photographs From the Collection of Los Angeles Public Library (2018) is a tribute to Central Library and follows the history from its origins as a mere idea to its phoenix-like reopening in 1993. Published by Photo Friends of the Los Angeles Public Library, it features both researched historical accounts and first-person remembrances. The book was edited by Christina Rice, Senior Librarian of the LAPL Photo Collection, and Literature Librarians Sheryn Morris and James Sherman.The book can be purchased through the Library Foundation of Los Angeles Bookstore.