A number of travelogues have been written about Los Angeles throughout the decades with a myriad of opinions on the cultural and social climate of the city. The City of Angels has been both praised and reviled in equal measures, but there is no question that it always leaves a lasting impression. One of the earliest and least known impressions of the City of Angels came from a Hungarian bon-vivant who, in 1857, passed through the city while on his way to Fort Tejon.

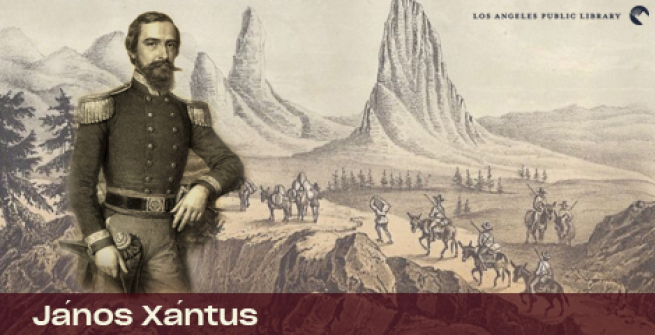

Janos (John) Xantus was born October 5, 1825, in Hungary while it was still part of the Austrian empire. After fighting in the Hungarian War of Independence, he left Europe to travel to the United States. Arriving in 1851, Xantus made his way across the United States falling into an assortment of adventures that were recorded in letters and a travelogue that was eventually published. During this period he managed to work for the U.S. Geodetic Survey and the United States Coast Survey in Baja California. He also enlisted in the U.S. Army and served in a consular post to Mexico. In 1857, he found himself in the newly established state of California. He had arrived with orders that he was to be posted at Fort Tejon, a military outpost at the edge of Kern County. It was at Fort Tejon that Xantus would come into his own as he began to document the flora and fauna of Southern California. Much of this documentation would end up at the Smithsonian Institution, serving as a cornerstone of the Smithsonian’s information about the natural history of Southern California. Xantus continued to document California’s ecosystem after his time at Fort Tejon and it garnered him much notoriety within the scientific community. But, before any of that could happen, he first had to get to Fort Tejon and the only practical way to get there was through a sleepy pueblo in southwest California called Los Angeles.

In May 1857 Xantus arrived in San Francisco. In his letters, Xantus compared the pre-1906 earthquake atmosphere and cosmopolitan feel of San Francisco to the great cities of Europe. He was certain that San Francisco had the potential to be one of the great metropolises of the world so it was quite a shock to the system when he arrived in Los Angeles in June.

Xantus’ boat docked in San Pedro on June 27, 1857. The port at San Pedro was not the efficient commercial hub of Los Angeles that it would grow into. Xantus arrived only a few years after Phineas Banning had come to San Pedro and started to develop the channel for commercial purposes. At this point, the main channel was only a few feet deep and commercial goods had to be brought up the channel via rowboat or barge:

We had a great deal of trouble disembarking, for the harbor is a very poor one, and also a contrary wind was blowing so that the steamer could not get near the coast. A small fishing barge came for us, but we had not gone halfway when it ran aground and, having no alternative, we all jumped into the water and in waist-deep water and ankle-deep sand dragged the barge for half a mile...

San Pedro has historically had a bit of a rough and tumble reputation and Xantus’ description of the town is not particularly favorable though his description of the place reveals his inclination for exaggeration and his tendency to be a bit dramatic, something that becomes apparent throughout his writing. His biography on the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History’s website reads as follows:

He has been described as, a most unusual man, a mixture of real scientific ability and general unreliability. Xantus's accounts of his own career are often highly embellished, sometimes to the point of mendacity. His superiors frequently found his work unreliable, and he never remained in any position very long. He was, however, a superb and dedicated collector.

Keeping that in mind, the July 1 letter he had written to his mother he states that he paid $3 for the opportunity to eat “roasted rats” and sleep on a “dirty reed mat” while he spent the night in San Pedro. The following morning, he hired three mules and made his way north to Los Angeles.

Los Angeles will always have its share of critics. Barbed criticisms from "cultured" personalities like Dorothy Parker, F. Scott Fitzgerald and Henry Miller are nothing new and, in fact, have become part of the L.A. folklore so the fact that John Xantus didn’t particularly like Los Angeles isn’t that surprising. Xantus, who been so enamored with San Francisco and had grown up in the splendor of the Austrian Empire, pretty much despised L.A.

The tone of his descriptions is pretty harsh, particularly when he speaks of the people and the buildings. He describes the houses as small and generic with “prison-like exteriors” and “endless covered porches”. Women could be seen peering out from behind windows covered with iron or wooden bars night and day. Much of this description seems to fit with the early Hispanic colonial architecture along the lines of the Avila Adobe, unfortunately, Xantus just didn’t seem to have an affinity for it. He was also horrified by the state of L.A’s churches which “judged by the state of their crumbling decay must be at least 100 years old.” He observed that half the city’s area is occupied by “churches and other religious institutions” which would lead observers to believe in the piousness of the city’s population when it was clear that the opposite was true. Of course, any great travelogue, worth its weight gives a sharp analysis of food and food service. Again, Los Angeles seemed to fall short on all accounts:

For the few who have had the misfortune of visiting Los Angeles, this metropolis of Southern California, there is not even a semblance of a public eating place. We were forced, therefore, like many others, to rent quarters. After obtaining them, naturally, we had to secure our meals. For this, we had to go to either a “Fonda” (Spanish Inn) where we could get poor quality food at prohibitive prices, or hire a cook, (thank heaven there are many of them), or start a household which is inconvenient. Should we decide on the latter, which at any rate is the better choice, we must consider the following: either to buy the kitchen supplies ourselves in which case the cook steals most of them, or send the cook to the market and he steals the cash. Of the two alternatives, the latter is better, provided the cook is not overly greedy. For my part, I do not recommend firing the cook for stealing; in fact, I suggest to one who has no cook, hiring one recently dismissed for theft. A suspected thief is not nearly as dangerous as an unsuspected one.

In his defense, the Los Angeles of 1857 was a dramatically different animal than the city that would emerge in the twentieth century. Los Angeles of the 1850s was a classic lawless ‘old west’ town, often described as a cultureless vortex awash with violence and crime so Xantus’ dislike of Los Angeles is a little more defensible than the New York literati critiques that took place in the 1930s. Nevertheless, Xantus had a flair for the dramatic and a tendency to embellish, so his descriptions have to be taken with a grain of salt. In sharp contrast to his hatred of the city, he gives a description of the landscape that shows his passion for the raw, natural beauty and physical geography of the region:

Los Angeles with a population of 500, lies on a beautiful plain on both sides of a river and offers a very pleasing view. With the exception of the western side, where the bare plain is filled with salty lagoons, it spreads as far as the Pacific Ocean. It is surrounded on all sides by high mountains. In the background glitter the snowcapped peaks of the Sierra Nevada. The little town also grows many grapes and tropical fruits and is engaged in an extensive trade of leather goods. It is also the seat of the judiciary of Southern California.

Some of this description is problematic: notably the “salty lagoons” and the peaks of the Sierra Nevada. Xantus may have confused details and maybe recounting his arrival in San Pedro and trek through coastal Wilmington as the salty marshes he writes about, however, the LA river was known to shift its course during the 19th century, possibly creating marshes in its aftermath but it’s difficult to be certain. Also, the snowcapped mountains are probably the San Gabriel mountains, not the Sierra Nevadas.

Looking Northwest at Mission San Gabriel’s southern exterior, [ca.1878]. Security Pacific National Bank Collection

Looking Northwest at Mission San Gabriel’s southern exterior, [ca.1878]. Security Pacific National Bank CollectionWhile in Los Angeles, Xantus also managed to trek out to both Mission San Gabriel and Mission San Fernando and was able to provide a nice description of Mission life in the mid-19th century. At San Gabriel, he met the priests at the monastery but had little interest in engaging in conversation; he did, however, accept a tour of the grounds where he (predictably) took an interest in the Tongva community that lived on the property. He noted approximately 140 Indigenous families who were skilled in artisan trades including blacksmithing, carpentry, weaving, tailoring, and farming. His primary interest, however, was fixed on the gardens and agriculture on the property:

The garden inspires admiration by all who appreciate beauty, comfort, and utility...large orange trees are planted alongside the roads which are heavy with fruit all year round and which form a beautiful shady, tree-lined avenue, through which sunshine barely penetrates. One entire section is planted exclusively with grapes which grow in such abundance that the mission sells 500 barrels of wine annually, not taking into account its own consumption. A second section is planted with greens, maize, barley, and potatoes. A third is planted with sugar cane and the fourth with banana, almond, pomegranate and fig trees. The entire interior fencing consists of lemon trees, which are trimmed to the same height as the adobe wall.

His description of the grounds at San Fernando is remarkably similar to San Gabriel. He notes approximately 1600 native people living on the grounds in small adobes adjacent to the mission. They were charged with caring for immaculately cultivated gardens that resembled the property at San Gabriel; again, most Mission residents were master tradesmiths:

During our stay at San Fernando, I visited the various shops to see for myself the progress of the natives. While they can make heavy blankets, all kinds of carpets and capes of extraordinary beauty, and manufacture all their agricultural tools from plows to kitchen knives themselves, still the equipment of the shops is quite primitive. Needless to say, this is not the Indians fault.

Many of Xantus’ descriptions are sympathetic to the native people, but his language, predictably, invokes the Eurocentric privilege that was commonplace at the time.

Xantus’ sketch depicting an ‘Indian weaving room’ at the San Fernando Mission,1858. [Letters From North America]

Xantus’ sketch depicting an ‘Indian weaving room’ at the San Fernando Mission,1858. [Letters From North America] Xantus drawing depicting Native American blacksmiths applying their trade at the San Fernando Mission,1858. [Letters From North America]

Xantus drawing depicting Native American blacksmiths applying their trade at the San Fernando Mission,1858. [Letters From North America]Xantus also shares his observations of and wonder at the equestrian skills of California’s vaqueros which he refers to as either ‘caballero’ or ‘cowboy’. Summarizing their appearance as an incarnation resembling the “Andalusian Knights of De Vega or Cervantes”, he then details their dress from the wide-brimmed hat, trousers slit at the side with red socks and jackboots ornamented with silver spurs; pistols and/or daggers are usually embellished with furry animal tails such as fox or squirrel. His fascination with their roping skills is, at once, obvious and actually inspires deep wonder and awe in our Hungarian visitor:

The California caballero seldom rides without a lasso, which is a long rope rolled with a loop on one end, and which he uses with extraordinary skill. In my childhood, I had heard of the custom in Transylvania and Bukovina of catching horses with a loop, but I have never seen anything like it in Europe. It seems certain that at present this weapon is only used in Spanish America...The Spanish Americans use the lasso for various purposes, among them to gather wood. The California caballero never dismounts when he gathers wood; he stays on the horse and loops the lasso around a tree trunk or log. He fastens the end of the lasso to the saddle and drags home the firewood. Wild cattle and wild horses and captured in the same fashion.

Xantus left Los Angeles sometime during the second week of July and headed out towards Fort Tejon where he would begin his military service and set about documenting California’s wildlife for the Smithsonian. He had a number of other adventures in the Southwest United States and Mexico before he left the Americas for good in 1864. The letters he had written home to his family were published as the 1857 book, Letters from North America; two years later, Xantus followed up the first book with a travelogue focusing specifically on his time in Southern California, Travels in Southern California. The books were originally published in Hungary and were not translated into English until the 1970s when they were finally published in America in 1975.

Big thank you to librarian extraordinaire, Eileen Sever who first spoke of Mr. Xantus!